What's Ed Ruscha saying with his "word" works?

Learn how the artist, who celebrates his 78 birthday today, puts the "noise of everyday life" on to his canvases

Is the US artist Ed Ruscha a writer or a painter? He certainly works with words and has published twenty or so books. Yet no one would take in one of well-know ‘word’ paintings in the same way as they might read a novel, a newspaper or a magazine.

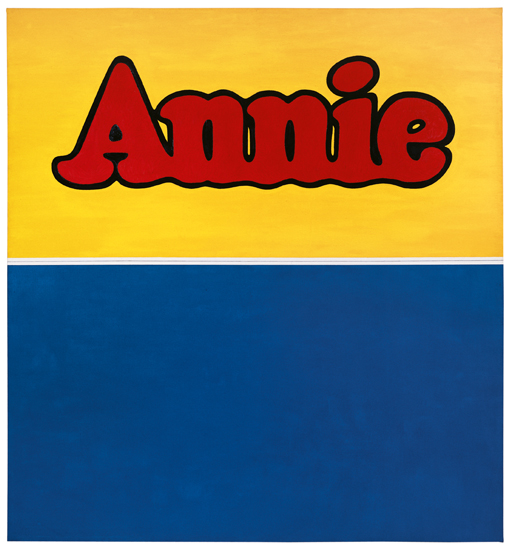

Ruscha has been painting, drawing and printing words on paper, canvas and in lithographs since the early 1960s, as the late critic and curator Richard D. Marshall explains in our Ruscha monograph, the artist began with simple, single word-works, such as Comics, from 1961, and Oof, from 1962, drawing inspiration from cartoon strips and other pop sources.

He moved on to multiple-word combinations in the following decade, with more obscure combinations, such as Cotton Puffs and Baby Cakes, both of which date from 1974.

Ruscha combined this extension of subject with a concordant development of materials; Cotton Puff is created using egg yolk; in Baby Cakes he uses blueberry extract to get his words down; while later works were created using tobacco juice, mint-leaf stains and gun powder.

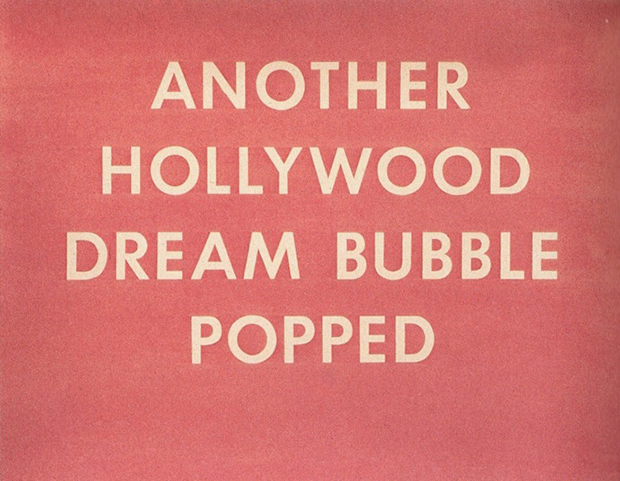

The sources for these longer strings of texts are less clear, although the artist has offered explanations in the past. “Some words are found ready-made, some are from dreams, some come from newspapers,” Ruscha says. “I don't stand in front of a blank canvas waiting for inspiration.”

Ruscha’s progression, from the kind of poppy words that wouldn’t have looked out of place in a Warhol print, to more cryptic text, was in keeping with the times. As Marshal points out, the artist’s more ambiguous pieces bear similarities to the work of conceptual artists like Bruce Nauman and John Baldessari, Jenny Holzer, who came to prominence in the 1970s and 1980s.

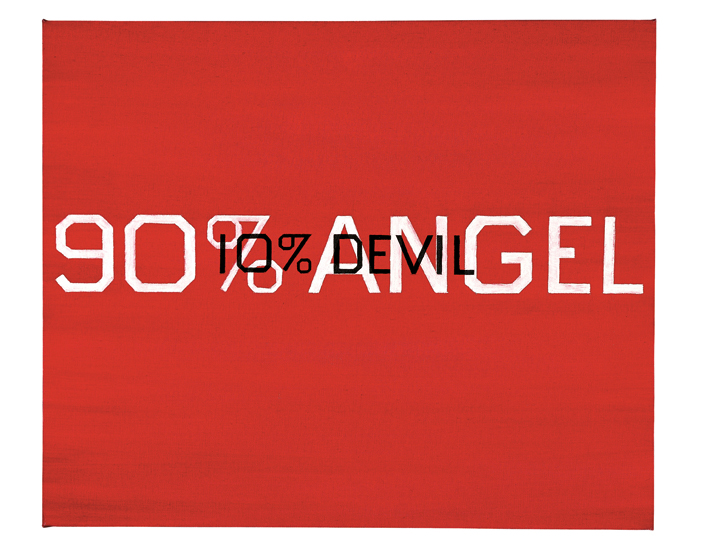

However, Marshall is careful to distinguish between the “strong physiological and emotional states relating to life and death,” evoked by Holzer, Nauman and co., and Ruscha’s phrases, which, in the author’s view, “are not concerned with opinionated content. Ruscha’s combinations have a more indefinite and illogical quality.”

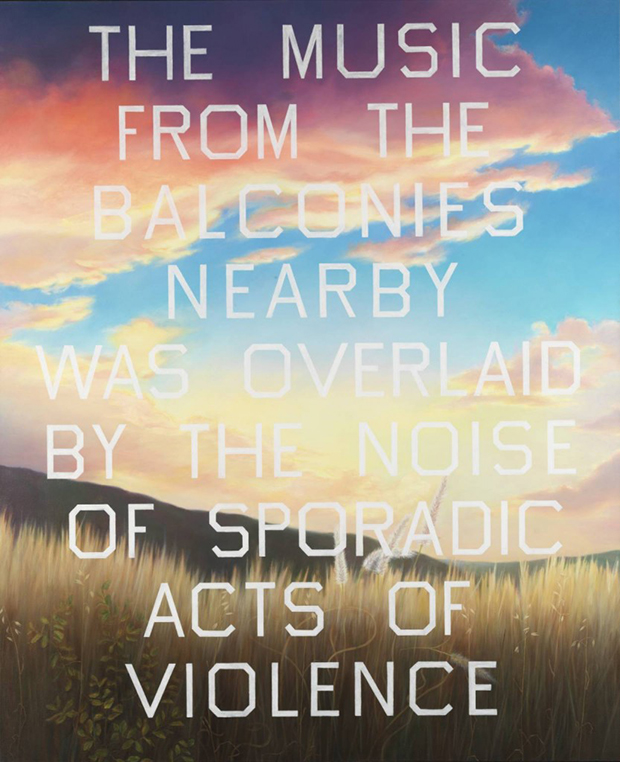

A few of the phrases, such as Artists Who Do Books, from 1976, clearly relate to Ruscha’s own life. Others, such as The Music from the Balconies was Overlaid by the Noise of Sporadic Acts of Violence, from 1984, is a directly attributable quote, in this case from the British novelist JG Ballard’s book, High Rise.

However, the phrases seem strongest when the source and meaning isn’t entirely clear, as the artist himself acknowledges. “Sometimes found words are the most pure because they have nothing to do with you,” Ruscha explains. “I take things as I find them. A lot of these things come from the noise of everyday life.”

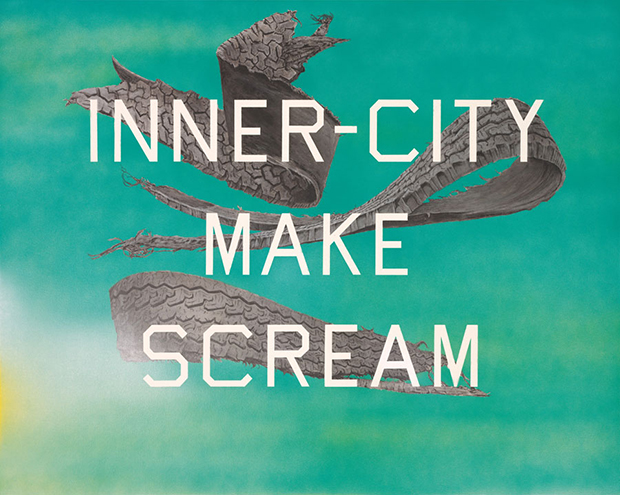

Look at paintings like Piggyback Daggers from 1976, Sea of Desire from 1990, or Inner City Make Scream from 2014 and you see how well Ruscha records that daily noise. If the words mean anything, perhaps they are simple records of those linguistic ear worms that we all come across; Ruscha’s artistry lies in his ability to get them down on paper without sharpening them, prettying them up or tuning them out.