Is Theaster Gates America's most exciting artist?

Our new monograph lays bare the civil, spiritual and capitalist components that make up this extraordinary artist

In 2013 Theaster Gates flew to Switzerland, to sell bank bonds in the home of European banking. These weren’t conventional investment instruments, and Gates, a 41-year-old African-American artist from the South Side of Chicago, had a background in pottery, religious studies and town planning, not high finance.

Indeed, the 100 bonds he took to the Art Basel fair two years ago were engraved on marble bathroom partitions salvaged from the derelict Stony Island Trust & Savings Bank, which the city of Chicago sold to Gates for a dollar, on the understanding he would raise the funds to turn the building into an arts centre.

Gates’ bonds, priced at $5,000 each, sold out, and the arts venue and artists’ residence, replete with a collection of 60,000 magic-lantern slides from the University of Chicago and the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, and the vinyl collection of the late Chicago house DJ Frankie Knuckles, will open this October.

It might sound like an unlikely property development, let alone a bone-fide art project, yet Gates, whom the New Yorker glowingly dubbed ‘the real-estate artist’, is quite used to thinking outside the white cubes of the gallery system.

Though he has produced pottery and paintings, sculptures, music and video works, Gates is best known, as we put it in our new monograph, for projects that “bridge the gap between art and life and encourage change by reaching beyond a traditional art audience.”

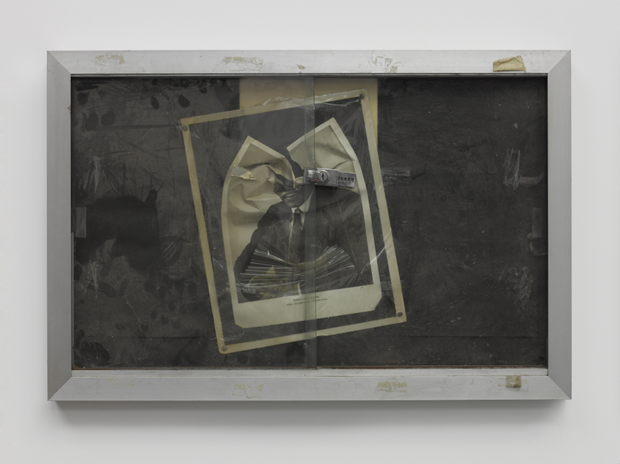

He saved remnants of derelict churches, created black-tar paintings in tribute to his father (a retired roofer), founded his own quasi-religious music group, The Black Monks of Mississippi, and repurposed, decommissioned fire hoses, of the kind used to spray civil rights protestors, into handsome, near-abstract collages. In each instance, a work’s success feeds back into a greater civic scheme that underlies almost everything Gates does.

In his mind, the art world shouldn’t wonder why he is behaving like a bank, a charity or a government department, but rather why fellow artists choose to limit themselves.

“One challenge for artists is to think of themselves as a sector,” says Gates in a wide-ranging interview with professor Carol Becker, which is reproduced in the book. “Maybe that’s why, in some ways, I sleep well at night, because I understand that what makes a thriving neighbourhood or a thriving city or a thriving environment is more a complicated mix of things.”

He adds that, “while I don’t identify as an activist, I do recognise the value of an ethical life and the importance of fighting for things you believe in.”

Our new Theaster Gates monograph comes at time when the artist is winning quite a few of his battles. The book’s publication not only coincides with the opening of the Stony Island Arts Bank, and the artist’s first UK public project, to be staged in a derelict Bristol church this autumn; it also arrives at a point when social practice, or a kind of art making that reaches beyond aesthetic limitations, to create intentional connections within artist and an audience’s greater social background, is on the rise. Think of fellow Phaidon artist JR’s current popularity; Assemble, the London architecture collective nominated for this year’s Turner Prize; or Ai Weiwei’s on-going tussles with the Chinese government, and you’ll recognise that Gates, at the vangard of this movement, is not alone in his ambitions.

He is also in good company as the latest addition to our ongoing Contemporary Artists series. Over the past two decades, these monographs have introduced such artists as Ai Weiwei, Richard Prince, Marlene Dumas and Marina Abramovic to a much wider audience.

Yet, while Gates’ work is clearly of an equal stature, he is quite distinct in creating these simple, exquisitely conceived, meticulously moral and artistic undertakings. The book reproduces plans and documentary photographs for all his best-known works, as well as pictures from the artist’s own archive, installation images and high-quality reproductions. Long-running photographic collaborator Sara Pooley shoots a visit to the artist’s studio; Lisa Yun Lee, the Director of the School of Art & Art History at the University of Illinois contributes an illuminating survey; while Achim Borchardt-Hume, director of exhibitions at Tate Modern in London, is the author of the book’s brilliant focus section.

Theaster himself has urged us to reproduce some of his own writings, including sketches, notes and diary entries, all of which offer unprecedented insight into his inimitable work, which combines a city planner’s eye for social environments, a believer’s feel for spiritualism, and an artist’s understanding of the sublime.

“I never thought of myself as a joy-production machine,” Gates says to Becker, “but it seems to be so.” To experience a little of this joy first hand, order a copy of this book here, and check back soon for more from this great new title.