A Movement in a Moment: Art Brut

How one French artist took the works of mentally ill patients and placed them at the forefront of Modernism

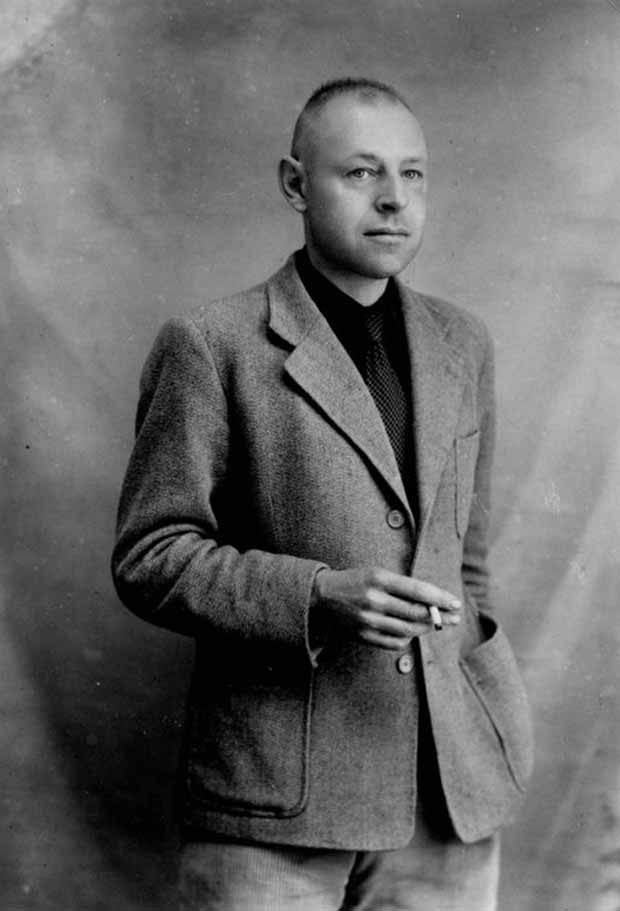

It was a two-week summer jaunt to one of the prettier countries in continental Europe. Yet for the French artist Jean Dubuffet, this trip to Switzerland was no simple vacation. The painter, accompanied by Swiss-French architect Le Corbusier and French critic and publisher Jean Paulhan, visited the country 5-22 July 1945, at the invitation of Dubuffet’s friend, the Cultural Ambassador of French-Swiss Tourism Paul Baudry.

It is unclear whether Baudry believed that Dubuffet, then a rising figure within the French art world, would delight in the region’s meadows and hill towns, or uncover the less-obvious appeal of the nation’s famous sanatoriums. However, it was in the Swiss asylums Dubuffet focussed during his trip, as he gathered artworks unblemished by conventional sensibilities.

As Paulhan would later recall, Dubuffet “ran around the asylums” gathering “different drawings and gouaches”; works that would form the basis of his famous movement, Art Brut.

Dubuffet was already a practicing painter, with an interest in works made by psychiatric patients. As author John Maizels explains in our book Raw Creation, the French artist was greatly influenced by the German book, Bildnerei der Geisteskranken or Artistry of the Mentally Ill, which he first read in 1923, a year after it had been published.

Indeed, the art of the insane asylum had always attracted a small audience. Yet, as a member of the French avant-garde, Dubuffet understood how works by psychiatric patients fulfilled certain Surrealist ideals, in that they seemed to flow directly from the subconscious.

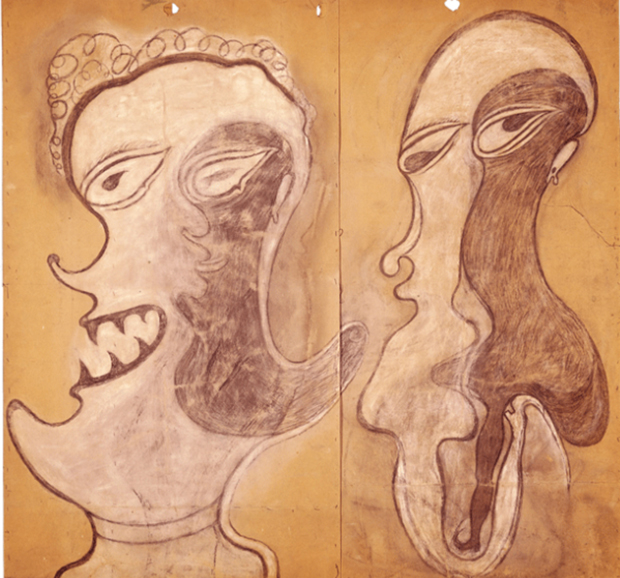

He had already begun to buy such pieces prior to his 1945 trip. However, it in the Swiss institutions that he truly established his mad collection. “He came across the works of [artist and psychotic sex offender] Adolf Wölfli and [French-born psychiatric patient and illustrator] Heinrich Anton Müller at the Waldau asylum,” writes Maizels, “he met [Swiss schizophrenic painter] Aloïse Corbaz at the psychiatric clinic of La Rosiere, near Laussanne, and saw the chewed bread sculptures of [Italian prisoner and sculptor] Joseph Giavarini at Basel prison.”

Dubuffet was sure that these artists fulfilled Modernist ideals better than the habitués of Parisian salons. Yet how could he get this across to the greater art world? Dubuffet knew that refined cultural circles would never accept a simple collection of works by lunatics. “He was aware of the stigma attached to ‘insane’ or ‘psychotic art’ and felt the need for a more dignified term,” writes Maizels.

It was this consideration in mind that Dubuffet wrote the Art Brut Manifesto in 1947, and, alongside fellow artist and author of the Surrealist Manifesto André Breton, and the art critic Michel Tapié, founded the Compagnie de l’Art Brut in 1948.

“Art Brut translates literally into English as Raw Art," Maizels explains, "raw because it is ‘uncooked’ by culture, raw because it came directly from the psyche, and, in its purest form, touched a raw nerve.”

In coining the term, Dubuffet switched the dysfunctional focus away from the mad inmates and towards the critics and galleries. His 1947 Art Brut manifesto declared that “We understand by this term works produced by persons unscathed by artistic culture, where mimicry plays little or no part (contrary to the activities of intellectuals). These artists derive everything - subjects, choice of materials, means of transposition, rhythms, styles of writing - from their own depths, and not from the conventions of classical or fashionable art."

As a movement, Art Brut captured certain Modernist sympathies, including the belief that an honest lack of sophistication was both morally and aesthetically superior – The Preference for the Primitive, as the art historian EH Gombrich once put it.

Perhaps this is why Art Brut drew a great deal of attention among the 20th century demi-monde. The dramatist and filmmaker Jean Cocteau; the anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss; and the painter Joan Mirò were all among it's admirers.

Unfortunately, by rejecting the art-world influence, Art Brut found it hard to sustain itself within the gallery system. Though Dubuffet continued to add to his Compagnie de l’Art Brut’s Collection de l’Art Brut, the works went on show just twice – once in 1949 at Paris’s Galerie René Drouin, and again in 1967 at Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Paris – before Dubuffet bequeathed the collection to the Swiss city of Lausanne.

Nevertheless, Dubuffet’s idea, that the strictures of the art world and society in general inhibit pure expression, remains potent. The photography of Roger Ballen, the drawings and animations of David Shrigley, and the renewed interest in outsider art – a more recent coinage that more or less expresses the same ideas – proves the art of the asylum patient can outlast the more mannered work on offer of the art-school graduate.

For greater insight into Art Brut buy our Raw Creation book; for more on art made outside the gallery system, get Wild Art. Meanwhile to understand how this movement fits into the greater sweep of art history, buy a copy of Art In Time.