Sonia Delaunay - Planes, Prints and Automobiles

In the second part of our chat with Juliet Bingham, the Tate curator talks us through Delaunay's later works

The new Sonia Delaunay exhibition at the Tate Modern in London (until 9 August) not only proves how important this early 20th Century artist was in helping to form Modernism, but also demonstrates how all-encompassing Delaunay’s work was, taking in clothes and interior design, fabric prints, needlework and collage, as well as all manner of self-promotion and presentation that, today, seems remarkably prescient.

This, the second part of our interview with the Tate's curator, Juliet Bingham, covers the theories behind Delaunay's Simultanism style of abstract art, as well as the position of decorative works in the artist's canon, and which arrangement in the new London exhibition Juliet is most pleased with. You can read the first part of the interview left.

Could you explain the ideas behind Simultanism? "Well, the critic Guillaume Apollinaire called Sonia and Robert Delaunay Orphists, though he also put a lot of artists under that umbrella term. Sonia and Robert rejected it. Instead, they described their art as Simultanism, which was to do with theoretical ideas that Robert was looking at - new scientific ideas about colour theory. Simultanism was about using simultaneous contrasting colours, as an activating force in modern life and modern painting. Sonia was less theoretically involved, but was perhaps more intuitive. Experiments in colour were very important to her. She took these ideas of simultaneously contrasting colours into the real world; into her paintings, but also her interiors, book bindings and clothes designs. In the exhibition there’s a dress she made in 1918, the first simultaneous dress, to go to parties at places like Paris’s Magic City pleasure garden."

It's unusual seeing these a pair of embroidered court shoes next to a more formal oil painting. Do you think Sonia saw the fine artworks as superior to the decorative pieces? "No, I think she saw them on an equal plane. She was expressing her ideas across media. She wouldn’t have made the distinction that one was necessarily more valid than another. Early on in Paris, when she and Robert were making their home in the city, conceived of their home’s interior as a kind of artistic environment. She covered in white linen, and she embellished lamp shades with different cut fabrics, so that they would cast the light in different ways around the room. In Spain too she worked with interiors, and in 1921, when they moved back to Paris, she created another three dimensional environment in their home, which became a great salon."

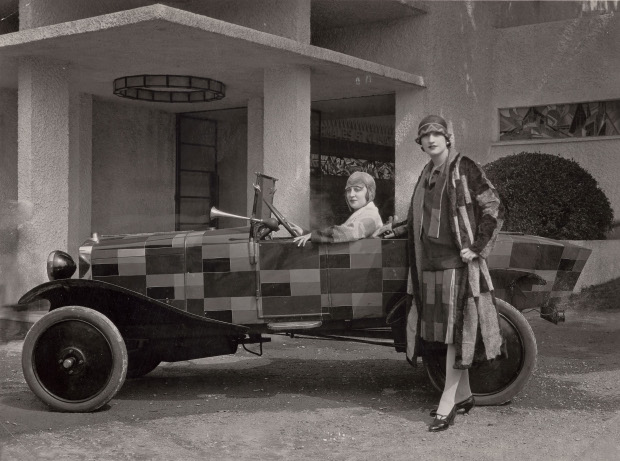

Do any of these interiors survive? "No, but the show has lots of documentary photography, because Sonia knew how to control her image. She was very careful as to how she marketed herself. She was her own brand in some respects. She set up her boutique Casa Sonia in Spain in 1918, and Maison Sonia in Paris in 1925. She also registered Simultane as a brand name and, through her workshop, made products under these names. She also worked very closely with certain photographers, like Germaine Krull and Florence Henri to specifically staging shoots of herself and her models, always against juxtaposing colourful backgrounds."

Most of the later pieces are abstract works, but there’s one room of huge figurative collages, assembled from images of aeroplane propellers and such. Tell us about this " Those date from 1937 and were a massive commission for International Exhibition of Art and Technology in Modern Life in Paris. Robert Delaunay was invited to oversee two huge pavilions, one devoted to air travel and the other devoted to railways. The exhibition was staged in part to boost trade. Robert and Sonia were given a collective of out-of-work artists to work on their project. Sonia sketched the designs for them. They are more realistic and diagrammatical than much of her other work, but you still see her style in the pieces and her use of colour. She gifted the aviation panel to the Skissernas Museum in Lund, Sweden in the 1960s. It came to the show rolled and it was a really interesting seeing the work re-stretched."

The exhibition also features some great fabric designs, including scarfs and ties made in Delaunay prints. Where did all that material come from? "Many came from the very large collection for her drawings that belong to Metz and Co, the department store in Amsterdam. Metz commissioned maybe 200 or more designs that were used for print silks or curtain fabrics. These were very well archived by Metz themselves. They have original sketches, swatch books and so on. Everything is really beautifully preserved, there has been quite good academic work on those materials."

How did your view of Sonia change in curating this exhibition? "I think I was just impressed by the breadth of her practice, and her consistency in expressing her ideas. She contributed to the first wave of abstraction and then later to the second wave; she was very supportive of a younger generation of artists, even if she felt her influence wasn’t always acknowledged. For instance, Sonia thought that [founding figure of op-art] Victor Vasarely did not recognise Robert and Sonia’s influence in his work."

The show has been open for a little over a week now. Is there a part you're particularly pleased with? "I like how three related works go together. These are Electric Prisms, a Le Bal Bullier and her first simultaneous dress. They give you an incredible insight into the modernity and vibrancy of urban life in Paris in 1913-14, and the way she presented herself as a living work of art."

Read the first part of our interview with Juliet Bingham in which she discusses Delaunay's early life, her place within art history and her marriage of convenience to Phaidon author Wilhelm Uhde. Meanwhile, For more on this new exhibition go here. For more on Modernism, consider this overview; and to learn about one later abstract artist who did acknowledge Delaunay as an influence, get our Harvey Quaytman monograph.