How Leonardo da Vinci used science to elevate art

On the anniversary of his birth, how the Renaissance Master used learning to raise the status of painting

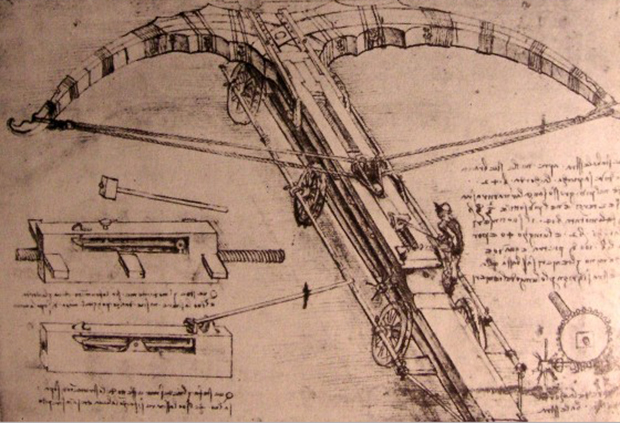

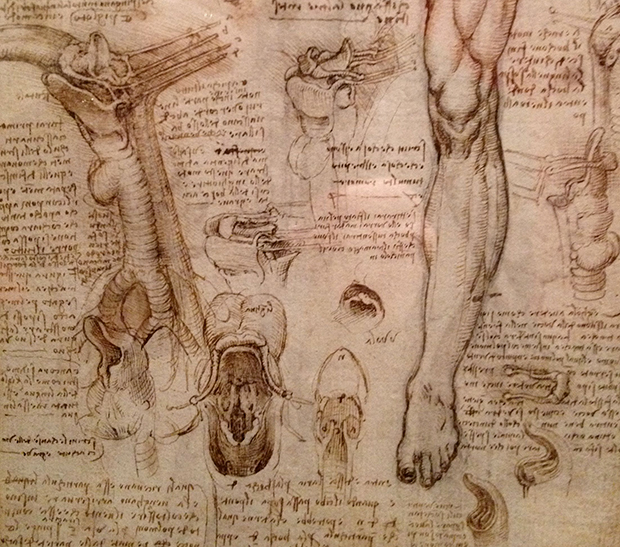

With his studies of biology and civil engineering, astronomy and human anatomy, the Italian painter Leonardo da Vinci is the polymath we think of when describing a Renaissance man.

Yet, today, on the anniversary of his birth, are we correct in regarding da Vinci as much a scientist as an artist? Not according to the great art historian EH Gombrich. He argues in his canonical work of art history, The Story of Art, that da Vinci did not take up these diverse fields of learning to distance himself from the role of the painter, but rather to elevate its position.

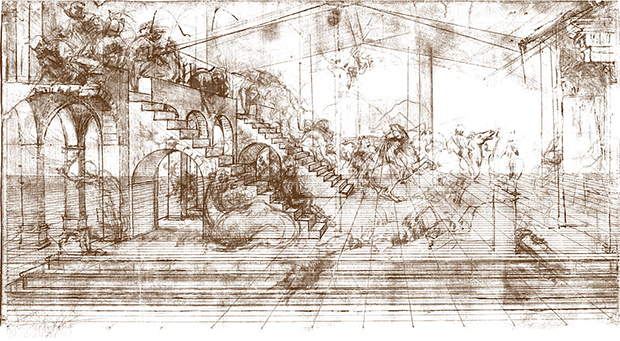

As Gombrich explains, da Vinci began his career apprenticed in the Florentine workshop of the painter and sculptor Andrea del Verrocchio where he studied metalwork, the human form, plants and animals, optics, perspective, and the use of colour, among other disciplines.

Da Vinci continued to pursue these and other areas of learning throughout his adult life, privately deducing such revelations as ‘the sun does not move’ in his notebooks, an assertion that perhaps anticipated the heliocentric theories of Copernicus.

How could a painter excel in such fields of knowledge? Perhaps because such learning improved both his art and the artist’s standing more generally.

“It is likely that Leonardo himself had no ambition to be considered a scientist,” writes Gombrich. “All this exploration of nature was to him first and foremost a means to gaining knowledge of the visible world, such as he would need for his art.”

To truly depict a person's physique, for example, da Vinci knew that he must first understand how a human's muscles and skeleton fit together. Yet scientific learning also served a social ambition, beyond improving his creation of art, as Gombrich acknowledges.

“He thought that by placing it on scientific foundations he could transform his beloved art of painting from a humble craft into an honoured and gentlemanly pursuit,” writes Gombrich. “To us, this preoccupation with social rank of artists may be difficult to understand, but we have seen what importance it had for men of this period.”

To comprehend this, Gombrich offers us a little background. “Aristotle had codified the snobbishness of classical antiquity in distinguishing between certain arts that were compatible with a ‘liberal education’ (the so-called Liberal Arts such as grammar, logic, rhetoric, and geometry) and pursuits that involved working with the hands, which were manual and therefore ‘menial’, and thus below the dignity of a gentleman. It was the ambition of such men as Leonardo to show that painting was a Liberal Art, and that the manual labour involved in it was no more essential than the labour of writing poetry.”

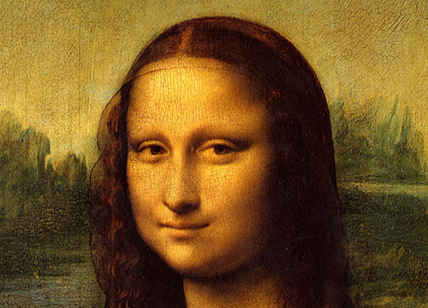

For an appreciation of how greater learning and study can improve a painter’s technique and standing, Gombrich alights on da Vinci’s best-known painting, which in turn demonstrates one of the painter’s best-known innovations.

“Mona Lisa (c. 1503-1506) really seems to look at us and to have a mind of her own. Like a living being, she seems to change before our eyes and to look a little different every time we come back to her.”

Decades spent studying colour, light, nature and human anatomy allowed da Vinci to create “his most famous invention which the Italians call ‘sfumato’ - the blurred outline and mellowed colours that allow one form to merge with another and always leave something to our imagination."

“Everyone who has ever tried to draw or scribble a face knows that what we call its expression rests mainly on two features: the corners of the mouth and the corners of the eyes. Now it is precisely these parts, which Leonardo has left deliberately indistinct, by letting them merge into a soft shadow. That is why we are never quite certain in what mood Mona Lisa is really looking at us.”

Scientific learning allowed da Vinci to improve the look of his works, and the way he was looked upon more generally – an elevation of both artistic practice and position that the fine art of painting is still enjoying today. Quite a birthday gift, we are sure you will agree.

For more on Leonardo’s work and his place within art history, buy a copy of The Story of Art here; for more on this particular period, consider Gombrich's three-volume examination of the Renaissance.