Gombrich Explains Frans Hals

Why should we delight in this Dutch painter? Well how about the spontaneity he brought to portraiture for starters?

As we approach publication we're getting increasingly excited about our new Frans Hals book, a monumental monograph devoted to one of the major painters of the Golden Age of Holland. Why should you care about this? Because, As art historian EH Gombrich makes clear in the best-selling art book ever, The Story of Art, Hals brought a degree of immediacy and levity to portrait painting that has never truly gone away.

Gombrich examines the painter in chapter 20 of The Story of Art, under the title The Mirror of Nature: Holland, Seventeenth Century. In it he explains how Hals and his contemporaries introduced lightness to the representation of people which, hitherto had been a formal, staid activity.

As with much of Gombrich’s writing he identifies the cause for this change within the context of greater world events. The reformation divided the Netherlands during the seventeenth century, with the Southern Netherlands, which we now called Belgium, remaining Catholic, and the Northern provinces adhering to the Protestant faith.

The Protestants never took fully to the Baroque style popular in Catholic Europe, preferring instead a more modest, devout style of art. “Painters,” writes Gombrich, “had to concentrate on certain branches of painting to which there were no objection on religious grounds.” Chief among these branches was portrait painting.

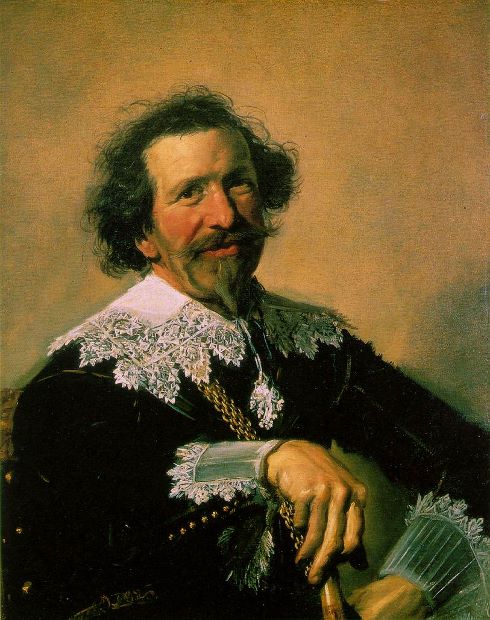

Hals, who was born in either 1582 or 1583 and lived until 1666, excelled in this art, possessing a talent for capturing both individuals and large groups in an informal, lively manner. Take, an early work, Banquet of the officers of the St George Militia Company, (1616) (above).

“Hals understood from the beginning how to convey the spirit of the jolly occasion,” Gombrich writes, “and how to bring life into a such a ceremonial group without neglecting the purpose of showing each of the twelve members present so convincingly that we feel we must have met them.”

Such a talent would keep Hals in work for most of his long life. Yet, his abilities are not immortalised in the canon of art history, because, Gombrich writes, compared with earlier portrait painters, Hals’ paintings “look almost like a snapshot.”

Yet his capacity for lifelike painting comes as much from his talent for balance and composition as from the speed and accuracy of his brush.

“The Portraits of Hals give us the impression that the painter has ‘caught’ his sitter at a characteristic moment and fixed it forever on the canvas.” Gombrich writes. “It is difficult for us to imagine how bold and unconventional these paintings must have looked to the public. The very way in which Hals handled paint and brush suggests that he quickly seized a fleeting impression. Earlier portraits are painted with visible patience – we sometimes feel that the subject must have sat still for many a session while the painter carefully recorded detail upon detail. Hals never allowed his model to get tired or stale. We seem to witness his quick and deft handling of the brush through which he conjures up the image of tousled hair or of a crumpled sleeve with a few touches of light and dark paint. Of course, the impression that Hals gives us, the impression of a casual glimpse of the sitter in a characteristic movement and mood, could never have been achieved without calculated effort. What looks at first like a happy-go-lucky approach is really the result of a carefully thought-out effect.”

For a greater understanding of this painter, and to see his works reproduced in exquisite detail, buy a copy of our new book; for more insight into this period and others, buy a copy of The Story of Art here.