Auguste Rodin’s battle with Balzac

On the anniversary of the sculptor’s birth we look at the botched commission that became a great work

Auguste Rodin, who was born today, 12 November, in 1840, is known both for his classical brilliance, and for his innovative, impressionistic flair - a latter-day heir to sculptors of antiquity and a worthy contemporary of Monet and Manet.

Yet not everyone appreciated these merits during his lifetime, as the troubles associated with one monumental sculpture make clear. In 1891, the writer Emile Zola became president of the French literary body, Société des Gens des Lettres, and appointed the 50-year-old sculptor to create a monument to the late novelist and playwright Honoré de Balzac.

While the commission should have been straightforward, the subject proved problematic. As the art history professor and Phaidon author Jane Mayo Roos explains in our Rodin monograph, “Balzac had been dead for forty years and he and Rodin had never met.”

Moreover, Rodin couldn’t simply fashion a bold, muscled likeness of the writer, since “the giant of French literature had been a short tubby man, ungainly in appearance and by his last years physically ravaged from the effects of overwork.”

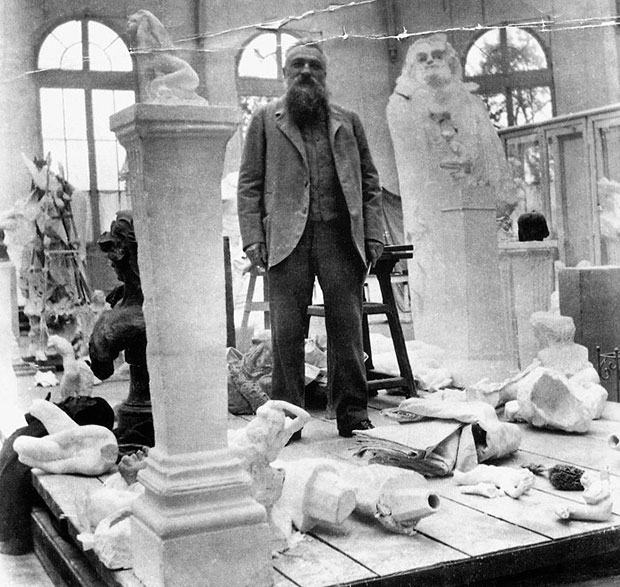

Nevertheless, Rodin sought to capture the late writer’s likeness. He studied photographs and portraits of the man, and even travelled to Touraine in central France where Balzac had been born, to examine the body types common in that area.

The more he looked, the more problems emerged. “The awkwardly protruding stomach,” Mayo Roos explains, “would be hard to conceal if the figure were dressed in contemporary garb.”

To overcome these difficulties the artist took to depicting the writer in a baggy, smock or houppelande. This appeared to satisfy his paymasters. In 1892, the Société forwarded him 5,000 francs, and the following year, Zola himself arranged for a second payment to be made, bringing the total received by the artist for this work to 10,000 francs.

However, Zola lost his position as the Société in 1894, and, the organisation's new management began to question whether its former president had been too high-handed in his dealings with the sculptor. It demanded a quick completion; Rodin demurred, and, finally two parties compromised. “A contract was drawn up whereby Rodin agreed to return the 10,000 francs he had been given, and the money was placed in a special account that could be accessed only upon completion and of the monument.”

Yet completion was still difficult. “Overworked and pressured from all sides,” writes Mayo Roos, “he began to show the strain.” The commission was worked and reworked, often in ways that captured the artist’s greater frustrations, rather than the spirit of the subject itself. “In several studies Balzac’s right hand grasps the end of his penis and holds it several inches outwards.”

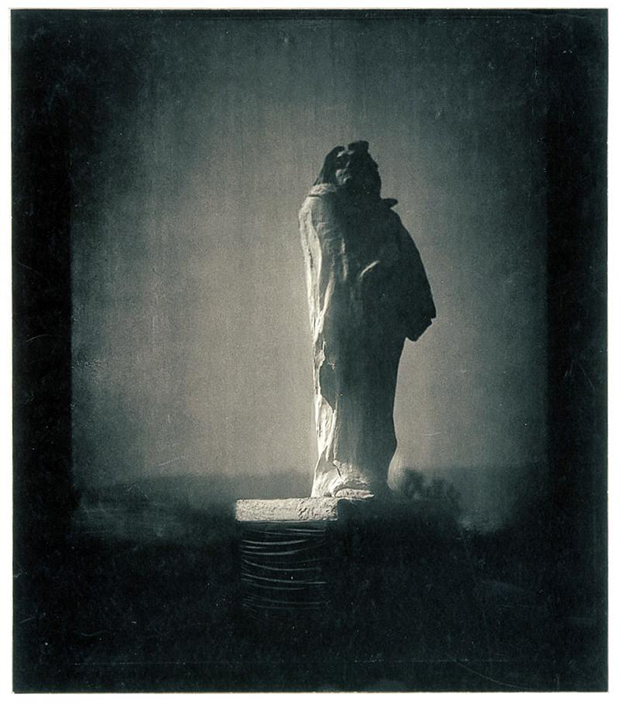

Rodin smoothed out these difficulties, and eventually exhibited his complete statue at the National’s Salon of 1898 in Paris. Public reception was mixed. Commentators described the work as being like “a block, a rock, a monolith”, “a toad in a sac”, “a snowman”, and “a penguin”.

Fellow artists were more sympathetic. “Oscar Wilde, the usually sharp-tongued Irish writer, called the statue ‘superb’," writes Mayo Roos, "and Claude Monet used the same word, writing to Rodin to say ‘it is absolutely beautiful and grand, it is superb and I cannot stop thinking about it.’”

“To be sure,” Mayo Roos goes on, “the statue was a far more original interpretation than the Société was willing to accept. Taking a Symbolist approach, Rodin evoked Balzac’s power as a creator, and the figure soars upwards from a small, rectangular base. Radiantly original in its conception, the Monument to Balzac simulates the unfolding of creative force and the ferocious immersion of the author of his work.”

Initially, it was unclear whether the Société would accept the work. Rodin feared rejection, and told the press: “Make no mistake this refusal of my Balzac would be disastrous for me. Don’t forget that I worked on it for five years and that, consequently, if the Société des Gens des Lettres does not pay me for my work, I will have uselessly employed at my age, five years of my life, without profit, without advantage.”

Unfortunately, politics were not on the sculptor’s side. Zola was, at this point, embroiled in the Dreyfuss affair, and any earlier commission of his was tainted. On 9 May 1898 the Société declared that it “refuses to recognise the state of Balzac,” withheld Rodin’s fee, and passed the commission to another artist.

Although distraught, Rodin kept work, in its raw plaster form, shipping the uncast monument to his house in in Meudon, where it languished until well after his death. Indeed, Monument to Balzac was only cast in bronze, in 1939, well after his death.

Nevertheless, this impressionistic, inchoate work has come to be regarded as one of Rodin’s greatest. The British art historian Kenneth Clark, the composer Claude Debussy, and the statesman Georges Clemenceau all numbered among its admirers, and bronze castings are listed in MoMA, while Edward Steichen’s photograph of the statue’s last (from which it is cast), taken at Rodin’s home in 1908, hangs in the Metropolitan Museum, New York. Not bad for a rejected work.

Rodin himself once said that, "I think of [Balzac’s] intense labour, of the difficulty of his life, of his incessant battles, and of his great courage. I would express all that.” Yet, on reflection, his words could serve as a comment on his own tribulations.

For more on this great artist's life and work, buy a copy of our Rodin monograph, here.