The strange story behind Willem de Kooning’s Woman I

On the anniversary of the Dutch abstract expressionist's birth, we tell the tale behind one of his infamous works

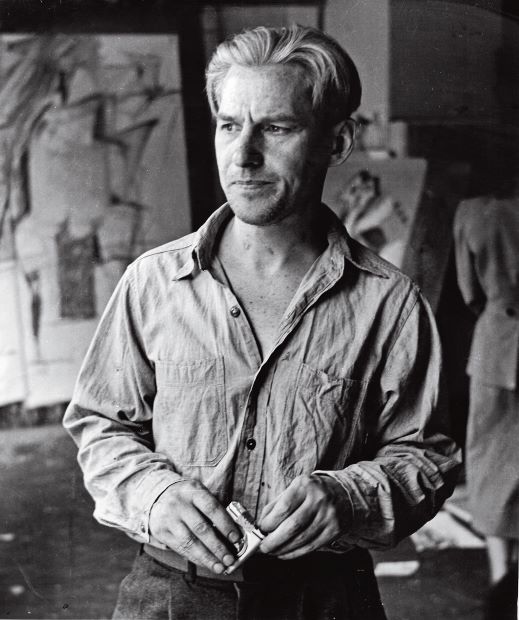

By the middle of the 20th century, Willem de Kooning had pretty much made it. Though he had arrived in New York as a 22-year-old stowaway in 1926, by 1951, as author Judith Zilczer writes in her book, A Way of Living: the Art of de Kooning, “he had already created an impressive array of controversial and compelling masterworks that have become touchstones for any account of twentieth-century art.”

And yet de Kooning’s place among the vanguard of New York’s abstract painters wasn’t something the artist accepted without question. Indeed, “his paintings resulted from a daring elision of abstract and figurative imagery that few of his contemporaries could fathom,” Zilczer writes.

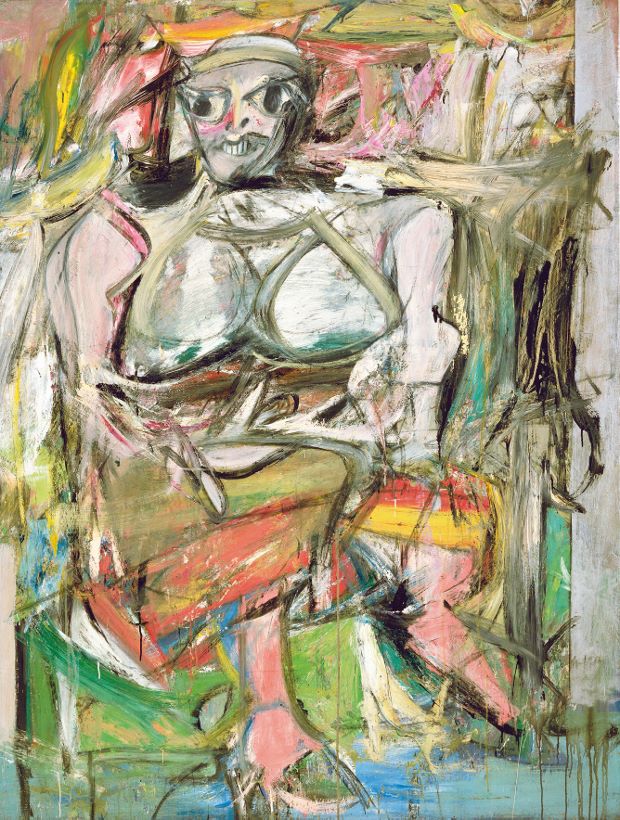

De Kooning both distanced himself most clearly from his fellow abstract painters and expressed this figurative interest most memorably in his Woman paintings, a series that began towards the end of the 1940s and continued into the following decade, upsetting both fans of his early canvases and those used to more genteel depictions of the female form.

These paintings, of buxom, vampish females, knotted up in swathes of abstraction, took detours from earlier ladylike forms into a new and violent direction. “If the facial and anatomical distortions of these figures reveal a kinship with Picasso’s famous series of paintings of Dora Maar, de Kooning’s handling of the figure within the space is far more fluid and energized than the rational geometry of Picasso’s Cubist interior spaces,” Zilczer writes.

The painter added dynamism to these new pictures, with the abstract “almost explosive force through the exuberance of his markings,” as well as laborious, collage-like treatments, as our book records.

“Working, as was his habit, with numerous drawings and collage fragments, de Kooning filled his canvas with image upon image, only to scrape away the figure and repeatedly begin painting anew,” Zilczer writes. “Elaine de Kooning estimated that some two hundred images preceded what is now the final state of Woman I.”

De Kooning, like Francis Bacon, also drew from found photography, often torn from magazines. “Fascinated by the image of alluring lips in cigarette advertisements, he incorporated collages of that ‘T-zone’ in a small painting of Woman, 1950, and in several of the early states of Woman I. In the final painting, however, de Kooning removed the collaged mouth and repainted the face with fang-like teeth and large, globelike eyes that echo the rotund shape of the woman’s enormous, pillow-like breasts.”

This constant reworking proved taxing. “Perhaps it is no wonder that the painter, dissatisfied with his progress, chose to abandon Woman I early in 1952.” Zilczer writes. Indeed, “de Kooning only resumed work on the painting now known as Woman I after art historian Meyer Schapiro, in what critic Peter Schjeldahl has aptly termed ‘history’s luckiest studio visit’, offered words of encouragement about the abandoned canvas during a visit with the artist at his Fourth Avenue studio.” This painting, and others in its series, went on show in New York later that year.

However, de Kooning’s struggles to paint the works were met with an equally tortuous critical reception, with many condemning the canvases as being violent and degrading towards women. Thankfully, the acclaimed critic, Clement Greenberg, best known for championing abstract expressionism, also praised de Kooning’s figurative turn.

“Greenberg, who had hailed de Kooning’s first solo exhibition five years earlier, claimed his painting belonged to ‘the most advanced in our time’, precisely because of the painter’s ambition to invest modern, abstract art with the ‘power of sculptural contour’ derived from the human form. Thus, Greenberg located the artist’s paintings of ‘Woman’ within a ‘great tradition of sculptural draftsmanship’ that encompassed the likes of Leonardo, Michelangelo, Raphael, Ingres and Picasso.”

High praise; though de Kooning may have preferred a fellow artist’s compliment, as Zilczer suggests. “Perhaps the most telling contemporary response to de Kooning’s work, however, came not from the critics but from another artist. In 1953 a young newcomer to the New York art scene, Robert Rauschenberg, approached de Kooning with an unusual request: he asked for one of the drawings of a ‘Woman’ in order to erase the image.

That de Kooning would grant such a request to destroy his work is testimony to his faith in art as a way of life. Rauschenberg may have intended his Dada-like gesture as an act of iconoclasm, but he was, in fact, emulating the older painter’s working method inasmuch as such acts of destruction had been integral to the birth of the series of paintings that would come to define de Kooning’s artistic identity.”

But that’s another story. For a richer understanding of de Kooning’s life and work buy a copy of the book here.