Gombrich Explains Katsushika Hokusai

Some good reasons to catch the Grand Palais show - the last time many prints will be seen outside Japan

Have you been to the Hokusai exhibition in Paris? The show, which runs at the city’s Grand Palais until 18 January next year, spans the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century artist’s entire career, and features a total of over 500 pieces, many of which, due to the fragility of the paper, will never leave Japan again. Indeed, the exhibition has been divided into two phases to protect the most fragile works, with around a hundred works replaced by equivalent prints, often from the same series during the course of the exhibition. Once a proposed Hokusai museum is completed in 2016 many of the works will never leave Japan again.

The works are beautiful, of course, but why should we take an interest in these images from an art-historical perspective? Because of the influence Katsushika Hokusai had on an earlier generation, as the great EH Gombrich explains in the world’s most popular art book, The Story of Art.

Gombrich addresses this in chapter 25 of the book, Permanent Revolution: the Nineteenth Century. The art historian argued that French Impressionists changed painting, by dismissing the worn-out conventions and practices that, despite being popular in academic painting, did not represent the world as they truly saw it.

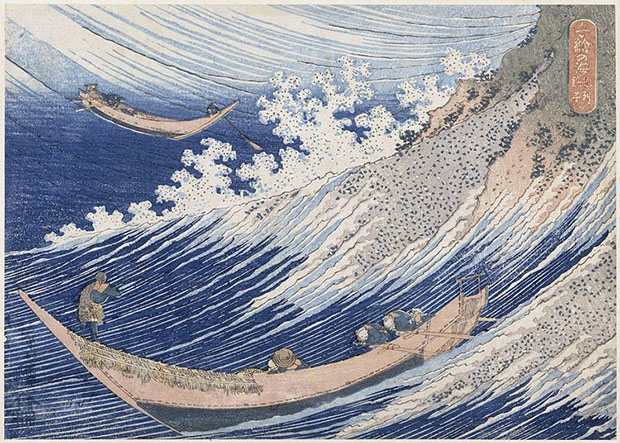

Where did painters such as Manet draw inspiration from, for this painterly iconoclasm? In part from the Far East. “Another ally which the Impressionists found in their adventurous quest for new motifs and colour schemes was the Japanese colour print,” Gombrich explains. “The art of Japan had developed out of Chinese art, and had continued along these lines for nearly a thousand years. In the eighteen century, however, perhaps under the influence of European prints, Japanese artist abandoned traditional motifs of Far Eastern art, and had chosen scenes from low life as a subject for colour woodcuts, which combined boldness of invention with masterly technical perfection."

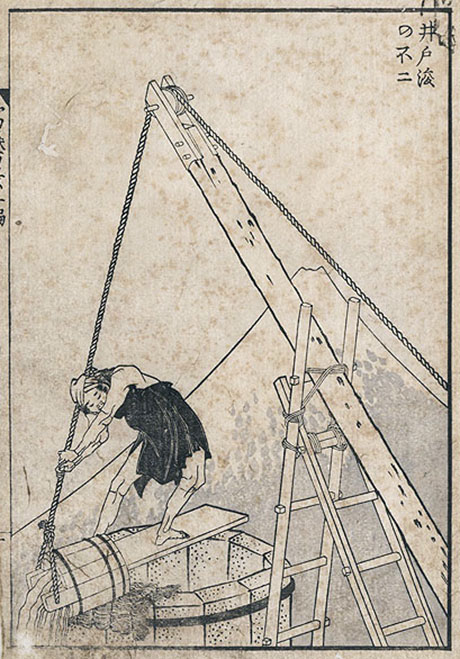

"Japanese connoisseurs did not think very highly of these cheap products," he goes on. "They preferred the austere traditional manner. When Japan was forced, in the middle of the nineteenth century, to enter into trade relations with Europe and America, these prints were often used as wrappings and padding, and could be picked up cheaply in tea-shops. Artists of Manet's circles were among the first to appreciate their beauty, and to collect them eagerly. Here they found a tradition unspoilt by those academic rules and clichés which the French painters strove to rid the world of. The Japanese prints helped them to see how much of the European convention remained without them really noticing. The Japanese relished every unexpected and unconventional aspect of the world. Their master, Hokusai, would represent Mount Fuji seen as by chance behind a scaffolding.”

Today, it's hard to see this image as revolutionary, yet these simple, matter-of-fact drawings - unlike anything being produced in Europe at the time - allowed Western artists to perceive very deep traditions in their own work, as Gombrich notes. “It was this daring disregard for an elementary rule of European painting that struck the Impressionists,” he explains. “They discovered in this rule a last hide-out of the ancient domain of knowledge over vision.”

For a richer understanding of this important artist, buy a copy of our stunning monograph. And more on Hokusai’s position in the canon more generally, buy a copy of The Story of Art, here.