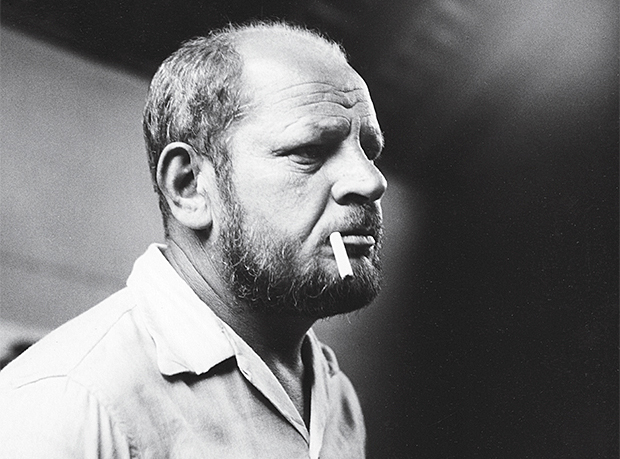

The final days of Jackson Pollock

On the anniversary of his death in a car crash we look at the last months of the great abstract expressionist

A memorial retrospective, held at the Museum of Modern Art four months after the death of Jackson Pollock, on this day in 1956 was notable not for what it included but for what it left out. Only five, possibly six, of Pollock's paintings can be ascribed to the last three years of his life, and none of them were included in the show that marked his passing.

Explaining the dearth of late work, the show’s curator, Sam Hunter, wrote that Pollock had had "periods of prolonged inactivity during the last three years of his life". Hunter referred to "the deep mental anguish of a paralysing spiritual crisis," which reinforced the impression that all Pollock’s efforts at redirection had failed.

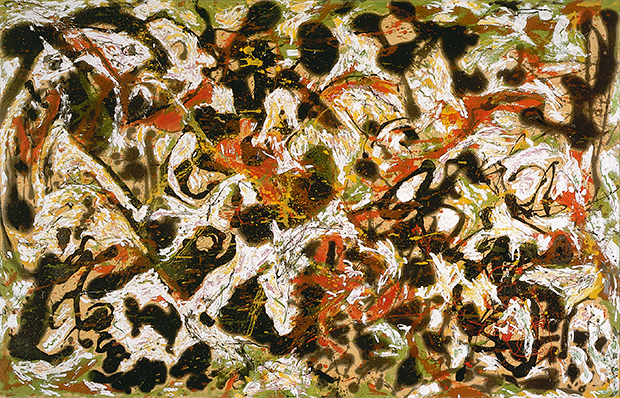

In fact, Pollock’s painting career culminated in a canvas aptly titled Search – a hybrid combining areas of dense, clotted pigment with viscous pourings – probably painted about a year before his death. Originally a vertical composition, signed and dated along what is now the lower-right edge, it was turned on its left side some time before its inclusion in a November–December 1955 exhibition at the Sidney Janis Gallery in New York. For this, the last solo show in Pollock’s lifetime, there was so little new work that Janis was forced to mount a mini-retrospective. Fortunately the earlier pieces were selling well, providing the artist with a comfortable income, some of which was spent on a round of psychiatric treatment that was to prove fruitless in curbing his drinking or relieving his depression.

If, (as our Focus book on the artist reveals), Pollock told the interviewer Selden Rodman, he believed that "painting is self-discovery", then this canvas, with its framework of graceful black arabesques accented by earthy green contrasting with dissonant overlays of intense opaque red and chalky white, expresses a deeply conflicted self. When the painting is viewed upright, as Pollock initially intended, its forms radiate positive energy, ascending diagonally and culminating in a cloud-like swirl. Rotated 90 degrees counterclockwise, however, its energy turns negative, implodes and flows downwards, as though it were being drained away."

So with his painting career effectively at an end, Pollock conceived the idea of pursuing his earliest artistic enthusiasm, sculpture. In the spring of 1956 he hired a tractor to dig up some of the glacial boulders on his property and had them piled behind the house. When friends asked about them, he said he planned to carve them, recalling his youthful desire ‘to mould a mountain of stone to fit my will’. However, the granite boulders outside his back door remained untouched.

In an abortive effort to find fresh impetus in three-dimensional form, Pollock created his last works of art. In July 1956, while visiting his friend Tony Smith, an architect who was then turning to sculpture, he made two small plaster pieces cast in sand. In Smith’s New Jersey studio, Pollock hollowed out a series of biomorphic shapes in damp sand, laid in an armature made of wire coat hangers, and poured liquid plaster into the mould. When the plaster set, he twisted the exposed wire to make a freestanding lobed object, about a foot long, that arches upwards like a primitive organism rising from the sea floor. Apparently, however, this experiment failed to inspire him, and he left the sculpture in Smith’s studio.

By this time, Pollock’s downward spiral had taken its final twist. In February, aged forty-four, he had begun an affair with a twenty-six-year-old aspiring artist named Ruth Kligman, further widening his rift with his wife Lee Krasner, who was losing hope that he would ever pull himself together and get back to work.

They had been planning a trip to Europe where, friends assured them, Pollock’s art was far more appreciated than it was at home and where, as critic, champion and friend Clement Greenberg had predicted, he would be hailed as a modern master. But with his marriage and professional life in shambles, and the hero-worship and sexual favours of a young lover to distract him, he decided not to risk humiliating himself in a sophisticated milieu that might recognize him as a has-been. In mid-July Krasner sailed for Europe alone, both to distance herself from the situation and to give herself time to decide what to do about it. The decision was to be taken out of her hands, however.

On 12 August, Krasner was in the Paris apartment of their friend, the painter Paul Jenkins (1923–2012), when a telephone call from Greenberg informed her that her husband had died the night before in a drunken car crash, in which Kligman was injured and another passenger, Kligman’s friend Edith Metzger, was also killed. The artist who led the vanguard of postwar American art with his pioneering method of painting, which broke with tradition in both subject matter and technique, was no more. For more on Pollack check out Morgan Falconer's masterful Painting Beyond Pollack and for a great introduction and overview buy our Phaidon Focus book.