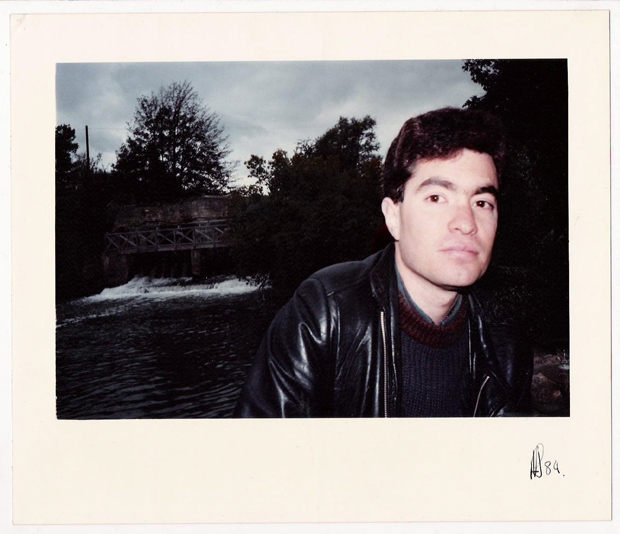

Knowing Kitaj: Marco Livingstone on his friendship with the artist

Livingstone's research for his thesis led to a lasting friendship with Kitaj until the artist's suicide

I first met Kitaj in April 1976 when, as an M.A. student at the Courtauld Institute of Art, I was researching my thesis on the work that he and a small group of fellow students at the Royal College of Art – David Hockney, Allen Jones, Peter Phillips and Derek Boshier – had produced between 1959 and 1962. I had, in fact, sought to write my dissertation entirely on Kitaj’s early work, but my tutors, Alan Bowness and John Golding, thought there might not be enough material for a dissertation of 10,000 words.

In the event, there was so much material from this fertile period in the work of five very inventive artists that Dr Golding graciously admitted I should have been allowed to concentrate just on Kitaj. Though the contact I made then with the other four artists was valuable, Kitaj remained a key figure - one whom all the others acknowledged as an influence and inspiration at a turning point in their lives.

John Golding was at that time in the middle of an intense series of sessions with Kitaj as the subject of a double portrait with his partner, James Joll. Kitaj returned the favour by agreeing to see me, the kind of distraction from his studio routine that he might well otherwise have avoided. He was expecting an artist friend for tea, the virtuoso French-Israeli draughtsman Avigdor Arikha, and his family, so on my arrival I knew that he would be able to give me no more than about two hours.

I went prepared with my tape recorder, as I had with the other artists I was meeting, only to be told that he was not fond of spontaneous conversations and that it would be preferable if I took notes. Less than a decade later, when badgering him with questions for the monograph that Phaidon had commissioned from me at his suggestion, it became evident that written correspondence suited him much better. As with his carefully planned paintings, the ability to consider his replies in his own time allowed him to be more precise in expressing his meaning. When, in the early 1980s, he first offered to revise the written transcript of our first encounter, he said to me, ‘Even if you wrote down exactly the words that I said, they might not have been exactly what I meant.’

We ended up with a voluminous correspondence conducted over two years, and then added to periodically when I was again writing about his art, curating a museum exhibition of his work (as I was to do in 1998 and 2004) or preparing a new edition of my Phaidon monograph. He was always immensely helpful and attentive to detail, with a stunning recall of books, art and people who had affected his outlook. For the fourth and final edition of my book, prepared in the aftermath of his suicide just short of his 75th birthday in October 2007, the sense of loss was made even more palpable by the unfamiliar situation of writing about new pictures without being able to ask him any questions about them.

Although Kitaj was only 43 when we first met, he had been in the public eye for over 15 years and already had a distinguished reputation. On that very first meeting he was already speaking about preparing for his ‘old age style’. I found him congenial but rather intimidating, as I was to continue to do during my visits to him in later years on Elm Park Road in Chelsea, where he lived with his companion (and eventually his wife) the American painter Sandra Fisher.

Around Kitaj it was difficult to ever let one’s guard down completely, and not only because his formidable intellect and wide reading could make one feel vulnerable and lacking in knowledge. Visits to his home tended to be planned with military precision and certainly with an American sense of time-keeping that fortunately was familiar to me from my own childhood in the USA. You were instructed to arrive for tea at, say, 4 on the dot, and it was always obvious when your audience with him had come to a close.

Only on my last visit to him in Los Angeles, where he had resettled in 1997 after turning his back on Britain, did I find him in a more relaxed mood that dispensed with the clock-watching. Should one have been fortunate enough to see him in the company of his old friend Hockney, whom he called affectionately ‘the blond bombshell’, an altogether more carefree side of his character was revealed: it was on such occasions that I saw him smiling, laughing and joking, all activities that he would normally carry out only with deadly earnestness. His humour was so dry you could easily miss it. Hockney, he told me once, had invited the curator Henry Geldzahler to stay at his mother’s house in the sleepy seaside town of Bridlington in East Yorkshire. ‘I told him to take a gun, it’s dangerous up there.’

Marco Livingstone is an independent art historian, critic and curator, and the author of the final edition of Kitaj