The story behind Andy Warhol's Heart paintings

Volume 6 of The Andy Warhol Catalogue Raisonné documents the enormously inventive period of Warhol’s career from mid-1977-1980, including his two series of Heart paintings

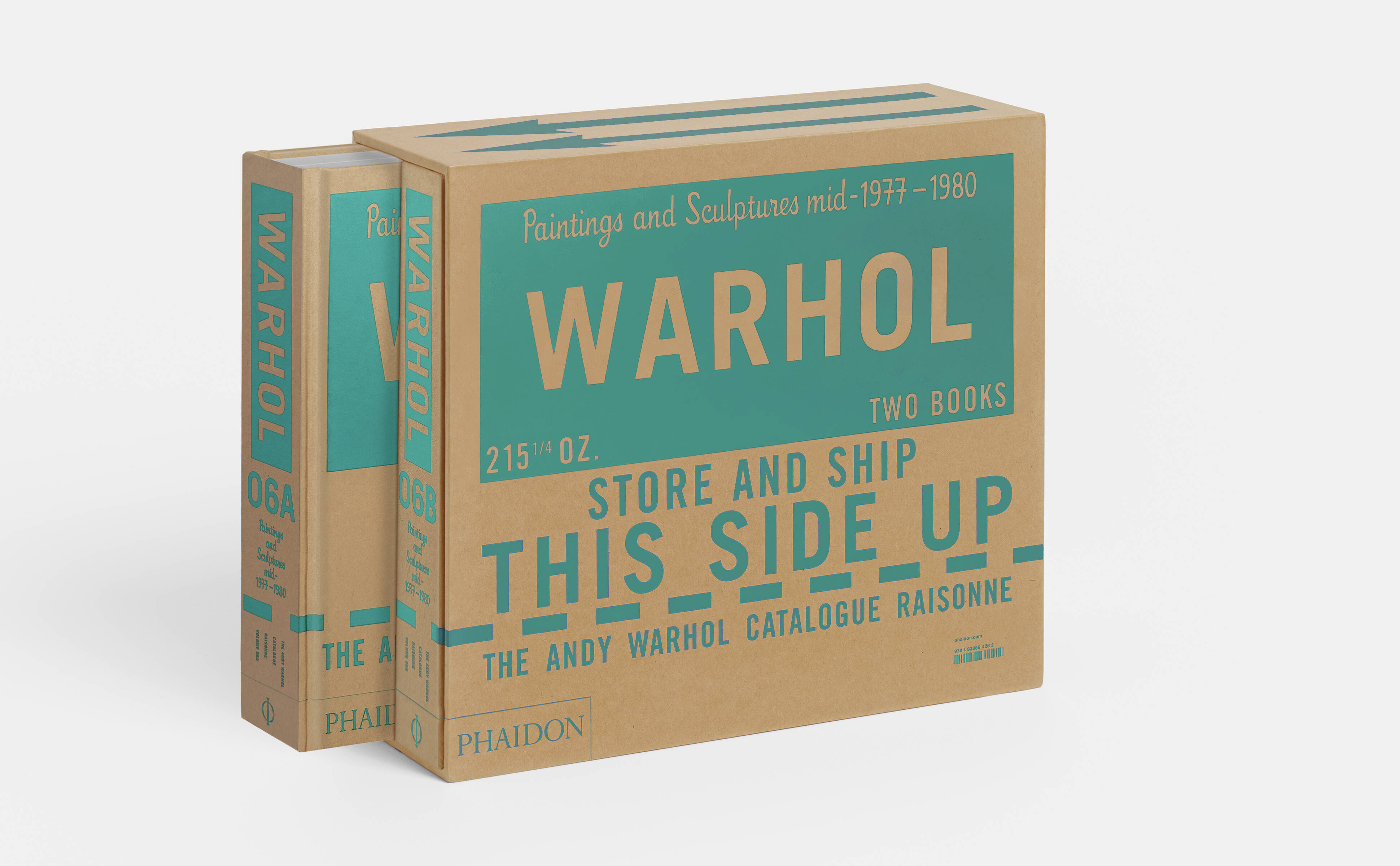

At 802 pages and consisting of two hardcover books in a slipcase with over 740 paintings and sculptures, Volume 6 of The Andy Warhol Catalogue Raisonné - the highly praised, definitive reference to Andy Warhol’s extensive artistic production - covers an enormously inventive and productive period of Warhol’s career from mid-1977 to 1980.

Today's story focuses on Andy Warhol's Heart paintings with text excerpted from the two volume set.

“In early 1979, when Warhol painted the ‘backgrounds,’ as he called them, for a group of small paintings to be distributed as handmade Valentines, two-thirds were multicolored and a third mostly monochrome. A field of black silkscreen ink printed over the paint layer framed the twinned chambers of the heart-shaped silhouette. Bob Colacello, who received one of the new Heart paintings as a gift, remembered it fondly in Holy Terror: ‘Andy gave me a tiny painting of a heart for my birthday that May [1979]. The heart was mint green, but the background was shiny black. He had done a bunch of small heart paintings for Valentine’s Day, “for all my 54 friends,” he said. Some were black and grey, others were candy-colored. I liked mine the best, because it was both hard and sweet–just like Andy, I thought. Andy had left it on my desk, wrapped in an Interview cover, which is what he usually used for gift wrapping. When I thanked him for it, he said, “Those are your favorite colors, aren’t they, Bob?” They were.’

“That Warhol intended the Heart paintings as Valentine’s Day gifts for his ‘54 friends’ directly links them to the Studio 54 Complimentary Drinks Ticket paintings he had recently produced as Christmas gifts for ‘all the Halston family.’ Indeed, to a large degree, Warhol’s ‘54 friends’ and ‘the Halston family’ made up much the same social set. Twenty-seven single Heart paintings produced in early 1979 have been documented by the Catalogue Raisonné to date, but it is noteworthy that only two are inscribed ‘H.V.D.’ [Happy Valentine’s Day] on the reverse, and both are dedicated to Warhol’s lover Jed Johnson.

“Prior to the gift paintings of early 1979, Warhol intermittently introduced hearts as whimsical, romantic, or erotic attributes of the figures in his early drawings of the 1950s, for example the heart on a string carried by the cavalier in the final plate of his 1953 self-published book, Love is a Pink Cake. Hearts are most abundant in the drawings he made of young men during the later 1950s and associated with an unrealized project, known as The Boy Book. In certain Boy drawings, tiny hearts flutter beside the mouth like a kiss, mirroring the silhouette of the lips, or are planted on strategic parts of the body, including the chest (where the heart lies) and the erogenous zone of the genitals.

“Touch is inscribed by the hand-drawn hearts of the 1950s and later autograph sketches in two ways: first as an intimate sensation, i.e., the act of touching the desired bodies of young men or the treasured souvenirs of fans; and second, as the embodiment of Warhol’s ‘touch,’ the personalized marks of his hand. For the paintings of early 1979, Warhol appears to have generated the silhouette of the heart from a readymade image or a stencil, in contrast to the irregular and variable shapes he drew by hand. His touch, however, comes into play in the hand-painted backgrounds of the multicolored canvases.

“The subject matter of the Human Heart paintings probably suggested itself to Warhol in response to a proposal for a public commission for the new headquarters of the National Institute of Health (NIH) in Bethesda, Maryland. With the commission in mind, Warhol painted a mural-sized canvas showing the organ serially repeated 156 times. The painting was the first of two proposals submitted to the NIH on his behalf, but both were rejected by the panel overseeing the commission. In tandem with the mural-sized canvas, Warhol also produced twenty smaller paintings of a single heart that vary slightly in size from 22 by 22 inches to 21 by 20 inches. The small Human Heart paintings were completed by September 1979, but whether they preceded or followed the mural is not known. Eight small paintings are based on the same image used in the mural; two other groups of six paintings each are based on different images. All three images are sourced from the photographic plates in two medical atlases. Like the mural, the smaller paintings failed to find a receptive audience during Warhol’s lifetime, and were exhibited only in 2002 at Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac, Paris.

“In a sense, the two bodies of work may be said to occupy polar positions within the spectrum of representation: from a rudimentary graphic notation to a photographically detailed specimen. They also derive from categorically distinct contexts: popular consumer culture, on the one hand, and specialized professional studies, on the other. Finally, their intended audiences couldn’t have been more different: the first series privately circulated as gifts, while the second, had it been accepted, a public-facing mural. Although they respond to different conditions and contexts, the two series were surely linked in Warhol’s mind. While he was casting about for ideas for the mural proposal, the motif of the heart, associated with personal feelings in the earlier paintings, may well have suggested itself as a promising image of a vital body organ for the NIH mural.

“Looking back on his Human Heart paintings Warhol observed in a diary entry on Monday, May 9, 1983: ‘Those Hearts of mine weren’t a hit because I didn’t figure out how to do them right. I was beginning to use my abstract look.’ If the 1977-78 Oxidation and Shadow paintings were Warhol’s first concentrated forays into abstraction—one camera-less, the other derived from photographs—the ‘abstract look’ he mentions in reference to the Heart paintings would seem to refer to something else, something that was not quite abstract painting per se, but in which abstract painting makes an appearance, inhering in the ‘look’ of the painting.

“It was, of course, the hand-painted portion of the Human Hearts—what Warhol called the ‘background’ of the painting—that was abstract, or to be more precise, a painterly, multicolored all-over field. The abstract look that Warhol was ‘beginning to use’ in his Human Heart paintings is a conspicuous feature in the painted backgrounds in his contemporaneous Reversal series, especially the mural-sized canvases of Marilyn. Multicolored, all-over backgrounds may also be noted among the smaller, serial compositions of the Reversal series (including Marilyn, Mao, Self-Portraits, and Cows), although they alternate with the monochromatic backgrounds more characteristic of Warhol’s ‘hard’ Pop style of the 1960s.” (Excerpted from Volume 6B, pages 9-11, 18)

The paintings and sculptures reproduced in The Andy Warhol Catalogue Raisonné: Paintings and Sculptures mid-1977–1980 (Volume 6) are accompanied by over 700 images of source materials, the artist’s Polaroids, contact sheets, and archival photographs of gallery and museum installations, as well as related works.

The editors of the catalogue raisonné and a team of researchers scoured the secondary literature, examined thousands of works of art, reviewed the artist’s archives and diary entries, and interviewed assistants, colleagues, portrait sitters, and friends to elucidate Warhol’s materials, techniques, and artistic process. Take a closer look here.