Cerith Wyn Evans on Art, Life, & Everything In Between

A tour of the Tate archive at the age of 12 proved revelatory for the Welsh contemporary artist who went on to forge a life of conceptual art brilliance

In 1976 a teenage Cerith Wyn Evans visited the Glynn Vivian Art Gallery in Swansea, Wales, and saw Michael Craig-Martin’s work, An Oak Tree.

The work, which comprises a glass of water on a shelf, accompanied by a text in which Craig-Martin claims that the glass of water has been transformed into an oak tree, proved revelatory to the young boy.

“It was this extraordinary impertinent act of magic made present. The auratic presence of an idea. A conceptual art. A transubstantiation,” the artist tells the curator Hans-Ulrich Obrist in Evans’s new Phaidon Contemporary Artist Series book. It was, he says, “something like a miracle.”

Few teenagers would have appreciated such a challenging work, yet Evans, who is today one of the UK’s leading contemporary artists, was, back in the 1970s, quite unlike his contemporaries. Born in Llanelli, Wales, in 1958, to Suwlyn and Myfanwy Evans, he developed an interest in the art world remarkably early.

By the age of 11 he had convinced his local library to stock periodicals such as Studio International and Flash Art. Aged 12, Evans’s father, a tailor and keen amateur photographer, drove them both to the Tate Gallery (now Tate Britain) in London, to see the works of Mark Rothko.

Cerith Wyn Evans, Take My Eyes and Through Them See You…, 2006. Artwork © Cerith Wyn Evans, 35mm film, plants, installation view at Institute of Contemporary Arts, London, 2006

Cerith Wyn Evans, Take My Eyes and Through Them See You…, 2006. Artwork © Cerith Wyn Evans, 35mm film, plants, installation view at Institute of Contemporary Arts, London, 2006

The paintings weren’t on display, but, as Evans told the Art Newspaper, “Alan Bowness [later director of the Tate] wrote me a letter, inviting me back to see the Rothkos, and a few months later he met me in person and took me backstage, downstairs. I think there were four that you could lift the polythene off.”

Evans returned to the British capital in 1977, winning a place at Saint Martin’s School of Art, where he studied under the acclaimed English artist and tutor, John Stezaker. He also landed a role as an invigilator at the Tate, where he gained a deep knowledge of the institution’s permanent collection.

The artist’s early output was as a filmmaker, producing his own experimental shorts; influenced by pioneers such as Kenneth Anger, while also working as an assistant on Derek Jarman’s films, including Caravaggio and The Last of England. The artist also produced films and music videos for such bands as The Smiths, The Fall, Throbbing Gristle, and Psychic TV.

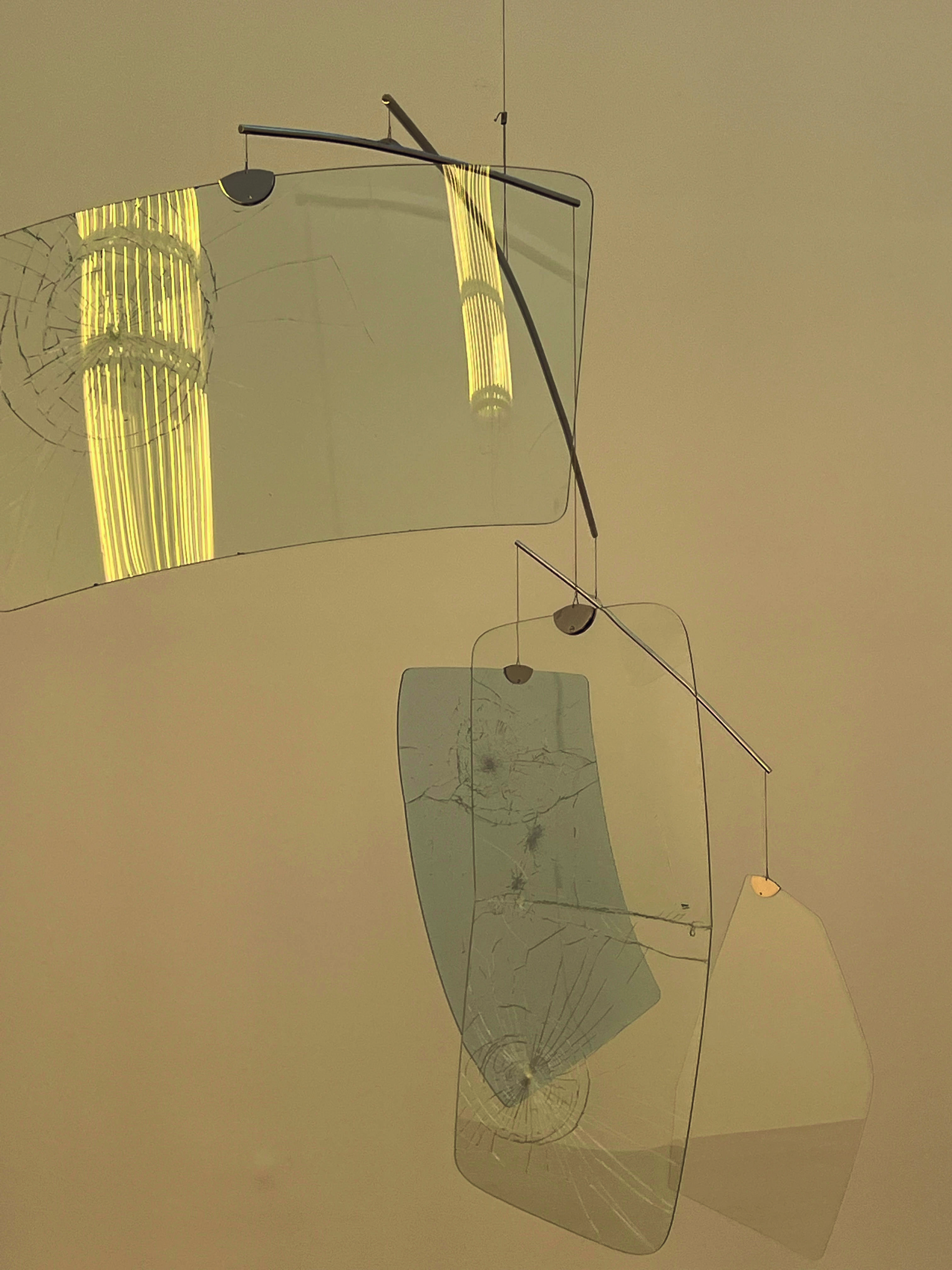

Cerith Wyn Evans, Phase Shifts (after David Tudor) (detail), 2020. Artwork © Cerith Wyn Evans, 4 screens, windscreen, mobile, Ø 500 cm

Cerith Wyn Evans, Phase Shifts (after David Tudor) (detail), 2020. Artwork © Cerith Wyn Evans, 4 screens, windscreen, mobile, Ø 500 cm

Yet, as the 1980s drew to a close, Evans began to branch out, beyond the moving image, to create sculptures, installations, photographs and works on other media, using a diverse array of materials, including fireworks, chandeliers, neon lighting, and plants.

Inverse Reverse Perverse, the huge, concave mirror from his 1996 White Cube solo show of the same name, was acquired by Charles Saatchi and shown in The Royal Academy’s 1997 group show, Sensation – a group exhibition widely regarded as a high watermark for the UK’s Young British Artists.

Cerith Wyn Evans, fig. (0), 2020. Artwork © Cerith Wyn Evans white neon, 730 x 707 x 519 cm, installation view at White Cube, London, 2020

Cerith Wyn Evans, fig. (0), 2020. Artwork © Cerith Wyn Evans white neon, 730 x 707 x 519 cm, installation view at White Cube, London, 2020

Evans never truly joined their ranks, but instead singled out his own influences which include John Cage, Kenneth Anger, Marcel Broodthaers and Marcel Duchamp, as well as figures such as Genesis P-Orridge and Brion Gysin, who straddled the divide between art, music and counterculture.

This list is by no means exhaustive; Evans’s art is filled with hidden references and esoteric meanings, drawn both from the artist’s personal experience, and from our wider culture, including Japanese theater, particle physics and classic rock, to name just three of very many sources.

Cerith Wyn Evans, TIX3, 1994. Artwork; Cerith Wyn Evans, green neon, 14 x 34 x 2 cm

Cerith Wyn Evans, TIX3, 1994. Artwork; Cerith Wyn Evans, green neon, 14 x 34 x 2 cm

His 1992 neon sculpture, TIX3, consists of a backwards exit sign, and was inspired by the moment when, upon deciding to leave the showing of a Hollywood film Evans had attended under duress, he found himself blocked in the exit corridor of the cinema. “All I could see was ‘TIX3’ - ‘exit’ written backwards,” he later recalled. “The work is about being in a space you are not ‘meant’ to be in.”

The artist’s 1998 work, Pasolini Ostia Remix, consists of a 15-minute film, shot on the banks of the Tiber, where the badly beaten body of the murdered film director Pier Paolo Pasolini was discovered. In this location, “four men erect a billboard bearing a text taken from Pasolini’s screenplay for Oedipus Rex (1967): ‘the banks of the Livenza / silvery willows are growing / in wild profusion, their boughs / dipping into the drifting waters’,” writes curator Nancy Spector in Evans’s new book.

Cerith Wyn Evans, installation view at Neu Galerie, Berlin, 2016. Artwork © Cerith Wyn Evans ‘E=L=A=P=S=E’ in Glass with Sound, 2016, 11 pieces toughened low iron glass, 5 channel audio, 11 speakers, 3 amplifiers, 1 waveplayer8, clear audio wire, 1mm stainless steel cable, 196 x 520 x 470 cm

Cerith Wyn Evans, installation view at Neu Galerie, Berlin, 2016. Artwork © Cerith Wyn Evans ‘E=L=A=P=S=E’ in Glass with Sound, 2016, 11 pieces toughened low iron glass, 5 channel audio, 11 speakers, 3 amplifiers, 1 waveplayer8, clear audio wire, 1mm stainless steel cable, 196 x 520 x 470 cm

The idyllic setting described here is none other than the site of the Italian filmmaker’s own childhood, which, when recalled against the backdrop of the litter-strewn sand in Ostia, makes a stark contrast between past and present. The individual letters are composed from twisted cords of gunpowder – fireworks – which are ignited as the sun sets. Evans captures their sequential combustion, filmed at eye level with the horizon, in a ritualized tribute that seeks to free Pasolini’s soul – a tribute and an exorcism.”

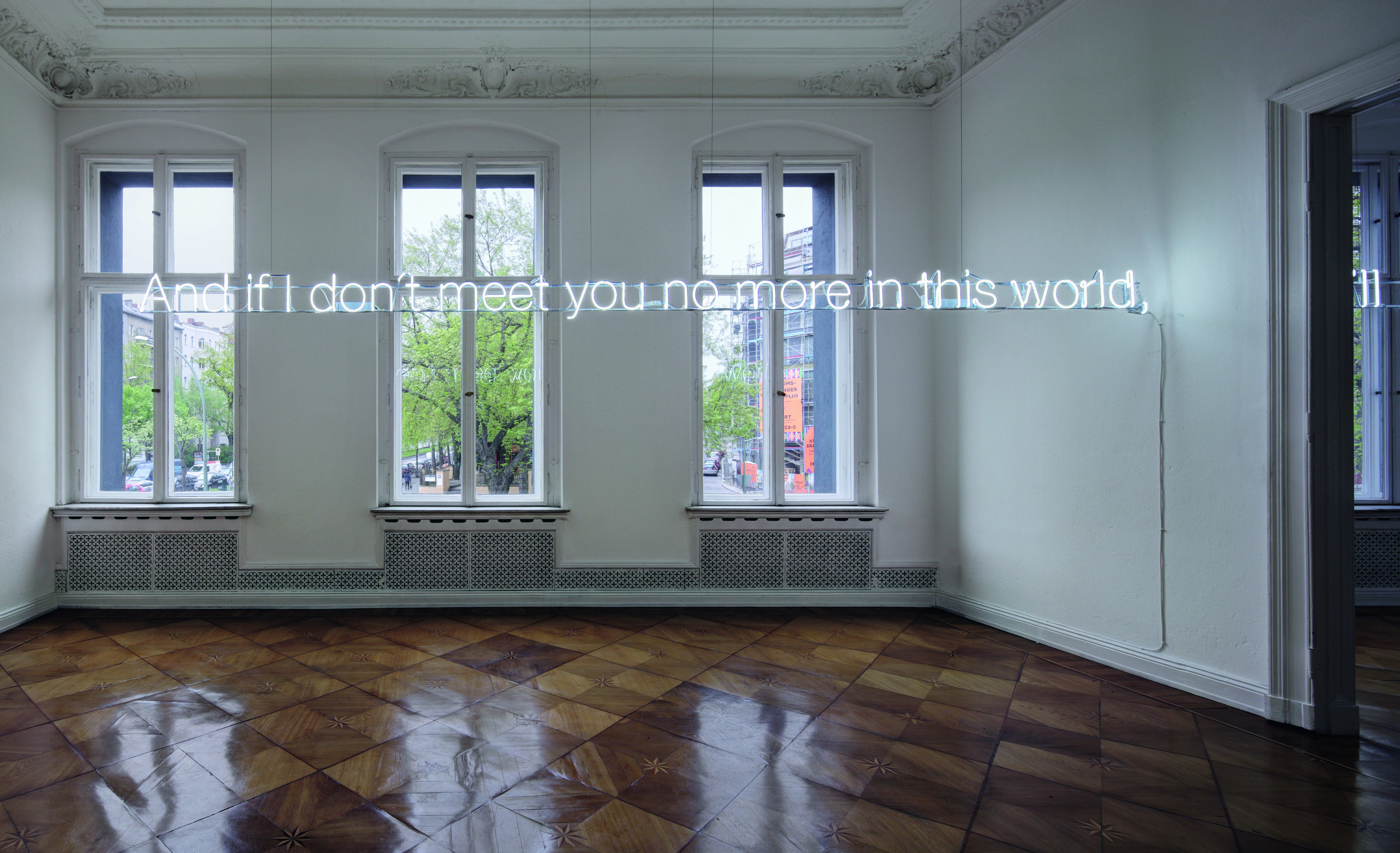

His 2012 piece, Voodoo Child, seems simpler; and reproduces a line from the Jimi Hendrix song of the same name.

Evans’s neon work from the following year, however, is a little harder to handle. Entitled Community Predicated on the Basic Fact Nothing Really Matters, it was inspired by the artist’s trip to CERN’s Large Hadron Collider in Switzerland and references the hypothetical model of particle physics investigated there, while also featuring depictions of another great Swiss discovery: the molecular compound for LSD.

Cerith Wyn Evans, The Illuminating Gas…(after Oculist Witnesses), 2015. Artwork © Cerith Wyn Evans, white neon, 378 x 319 x 191 cm, installation view at Pola Museum of Art, Hakone, Japan, 2020

Cerith Wyn Evans, The Illuminating Gas…(after Oculist Witnesses), 2015. Artwork © Cerith Wyn Evans, white neon, 378 x 319 x 191 cm, installation view at Pola Museum of Art, Hakone, Japan, 2020

“With this resonant juxtaposition,” writes Spector, “Evans makes a correlation between the exploding theories of the cosmos with the expansive capacities of the brain, unleashed by psychotropic agents.”

All heady, challenging stuff. Evans accepts he doesn’t open himself up to simple interpretations. “It is not meant to be deciphered or comprehended,” writes Spector, “rather, his work is to be sensed, experienced subliminally, almost prelingually. Of course, the myriad, erudite references imply latent subtexts, but taken too literally, they get in the way of one’s intuitive understanding or, at least, experience of the work.”

Cerith Wyn Evans, installation at White Cube, Hong Kong Sar, 2022. Artwork © Cerith Wyn Evans clockwise from left: Speaker III, 2022, 1 piece toughened low iron glass, 1 stainless steel, hanging bracket, 1 channel audio, 1 speaker (audio exciter, 32mm type, 30w, 4 ohm), 1 amplifier (S.M.S.L.), 1 audio player, clear audio wire and 1mm stainless steel cable, 143 x 78 x 3 cm; Neon After Stella (Arundel Castle), 2022, white neon, 256 x 155 cm; Still Life (in course of arrangement…) VIII, 2015–22, plant and turntable, 276 x 180 x 180 cm; Speaker II, 2022, 1 piece toughened low iron glass, 1 stainless steel hanging bracket, 1 channel audio, 1 speaker (audio exciter, 32mm type, 30w, 4 ohm), 1 amplifier (S.M.S.L.), 1 audio player, clear audio wire and 1mm stainless steel cable, 143 x 78 x 3 cm; Neon After Stella (Tomlinson Court Park), 2022, white neon, 161 x 219 cm; Speaker I, 2022, 1 piece toughened low iron glass, 1 stainless steel hanging bracket, 1 channel audio, 1 speaker (audio exciter, 32mm type, 30w, 4 ohm), 1 amplifier (S.M.S.L.), 1 audio player, clear audio wire and 1mm stainless steel cable, 143 x 78 x 3 cm; Neon After Stella (Clinton Plaza), 2022, white neon, 205 × 161 cm

Cerith Wyn Evans, installation at White Cube, Hong Kong Sar, 2022. Artwork © Cerith Wyn Evans clockwise from left: Speaker III, 2022, 1 piece toughened low iron glass, 1 stainless steel, hanging bracket, 1 channel audio, 1 speaker (audio exciter, 32mm type, 30w, 4 ohm), 1 amplifier (S.M.S.L.), 1 audio player, clear audio wire and 1mm stainless steel cable, 143 x 78 x 3 cm; Neon After Stella (Arundel Castle), 2022, white neon, 256 x 155 cm; Still Life (in course of arrangement…) VIII, 2015–22, plant and turntable, 276 x 180 x 180 cm; Speaker II, 2022, 1 piece toughened low iron glass, 1 stainless steel hanging bracket, 1 channel audio, 1 speaker (audio exciter, 32mm type, 30w, 4 ohm), 1 amplifier (S.M.S.L.), 1 audio player, clear audio wire and 1mm stainless steel cable, 143 x 78 x 3 cm; Neon After Stella (Tomlinson Court Park), 2022, white neon, 161 x 219 cm; Speaker I, 2022, 1 piece toughened low iron glass, 1 stainless steel hanging bracket, 1 channel audio, 1 speaker (audio exciter, 32mm type, 30w, 4 ohm), 1 amplifier (S.M.S.L.), 1 audio player, clear audio wire and 1mm stainless steel cable, 143 x 78 x 3 cm; Neon After Stella (Clinton Plaza), 2022, white neon, 205 × 161 cm

Evans himself agrees. “There are many layers to it and multiple points of entry,” the artist told The Art Newspaper’s Louisa Buck in 2017. “Very importantly, my take is not the only take on it. If anything, it’s a kind of zone for meditation and a place for reverie on the transference of energy. I feel there’s an insufficiency of means to come to even a conventional description of what it is to live through a revolution in information technology and to look at the exchanges of energy that go across the surfaces of the earth, let alone what fantasies we might have about parallel realities. I want people to be in a place where they might be able to pick up on some of these things.”

He went on to add that his friend, the critic and art historian Molly Nesbit, described his work as “‘a rendezvous of question marks’, which I like very much.” Do you share the appreciation? Then take a look at our Contemporary Artist Series book on Cerith Wyn Evans’ and his artist page on Artspace.