.jpg)

John Stezaker - Why I Make Collage

The Vitamin C+ featured legend on why collage is like a card game, early inspirations, and discovering his first collage among his mother's personal effects

"Since the mid-1970s John Stezaker’s work has aimed at unpacking the technical, formal and conceptual foundations of collage," writes Yuval Etgar in Vitamin C+ Collage in Contemporary Art.

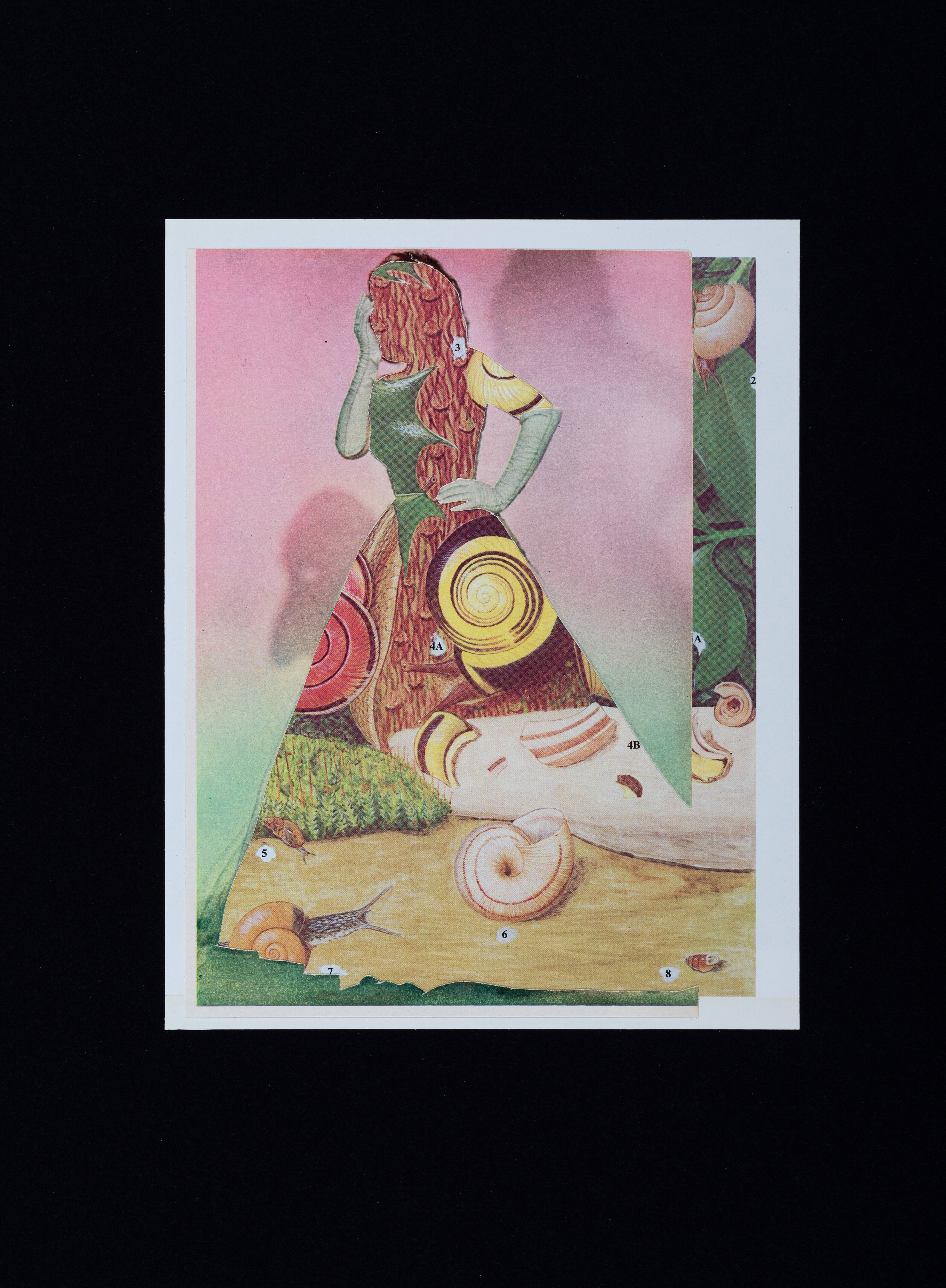

The London-based artist's works are characterised by two photographic elements - often from the world of film, photography or tourism - juxtaposed with one another. In his collages, Stezaker appropriates images found in books, magazines, and postcards and uses them as ‘readymades’.

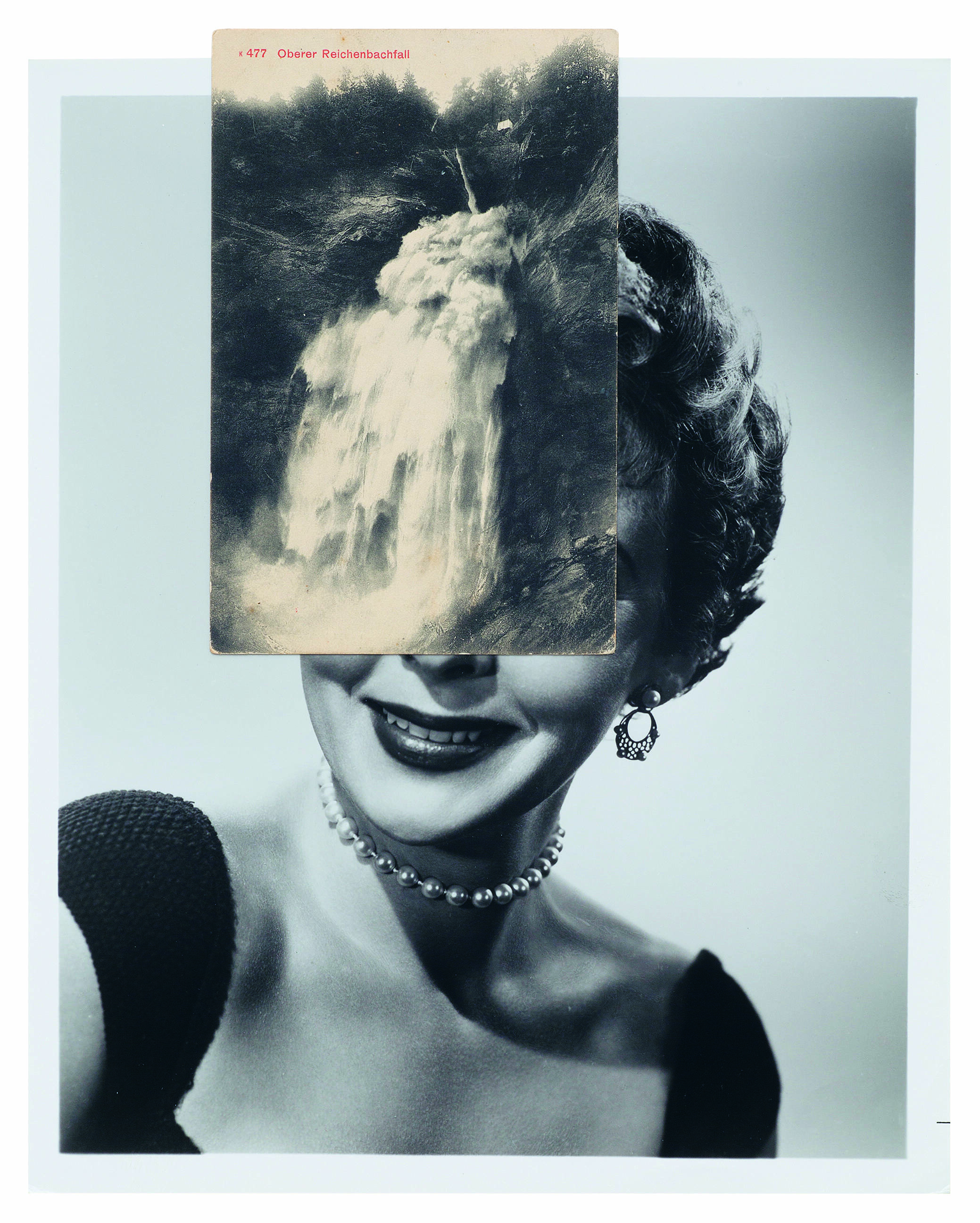

His best-known ‘Mask’ and ‘Insert’ series combine Cubist and surrealist influences in found postcards depicting natural landscapes from the early twentieth century with film-still photographs from the 1940s and 1950s.

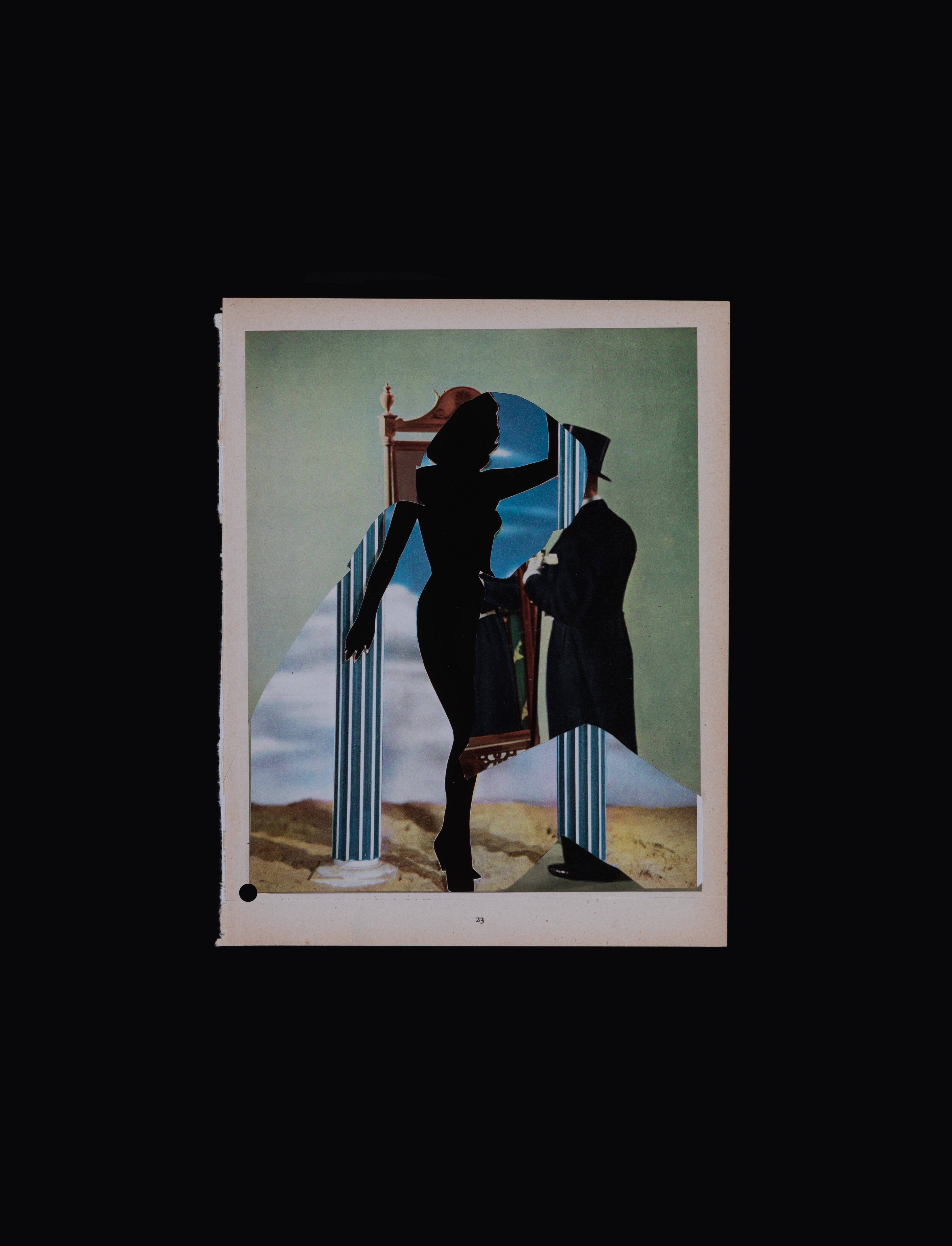

His ongoing ‘Double Shadow’ series, where the dark background infiltrates the image, creates "an anonymous placeholder for the viewer’s imagination to fill," according to Yuval Etgar.

Stezaker is one of 108 artists featured in Vitamin C+ Collage in Contemporary Art which showcases living artists who employ collage as a central part of their visual-art practice. The artists have been chosen by 69 experts in the field, including museum directors, curators, critics, and collectors. Yuval Etgar, an internationally renowned expert in the area provides the introduction and writes many of the excellent texts. Phaidon.com is talking to a select group of artists featured in the book.

We caught up with John Stezaker who told us why he sees collage as a "card game of risk", "an escape from duration", and how seeing one of his first ever collages when clearing out his mother's things after her death immediately brought back a memory of the taste of licking the fragments of the gummed paper.

John Stezaker - Double Shadow, 2021 Picture credit: © John Stezaker. Courtesy the artist

Who are you and what’s on your mind right now? I wish I could answer that. Does anyone know who they are or for that matter what they do? Blanchot observed that the writer is the least able to read their writings. Similarly, I’d say that artists are inherently blind to what they show in their work. It’s harder still to say, amongst the multitude of things, what is particularly on one’s mind. However, if the question is about what I might be thinking of doing next in the work, I can say that at present I am planning to pursue some work with Victorian and Edwardian illustrations, photo-engravings and gravures that I have broached mostly unsuccessfully - so far - from time to time over the past decade or so.

What draws you to collage, what are the properties that excite or intrigue you? Speed and mobility. I love the instantaneity of collage. It’s almost always already there. The components are present from the start. There is none of the instrumental work of conception and construction. One is free of the constraints of end-orientated activity and thus liberated from the slavery of teleological thought, in other words freed from the boredom of everyday activity. I have always seen collage as escape - from duration. I completely loose time when I am “working”. It is neither exactly a collapse of time, though I am often shocked to find how many hours have passed in what seem like moments of activity, nor an expansion, though at times the multitude of image possibilities can suggest a vast and momentous evolutionary process has taken place. It’s more a suspension of time. Blanchot refers to the “absence of time” of fascination. For me, collage is both mobility and stillness, becoming and being.

John Stezaker - The Kiss, 2022 Picture credit: © John Stezaker. Courtesy the artist

To the outsider, collage seems like the most freeing of mediums to work in, but is it? I find it so, but it is a freedom within limits as is all play. You accept from the outset the overall constraint of the limits of the available. But, this is the necessary limit for the freedom of playing. It is like the need for rules in a game. We need parameters within which we can take risk. I like to think of collage as a game of risk like a card game. Picasso and Braque in their early collages recognise this affinity by their inclusion of playing cards. I think they also recognised early on that this was a liberation from the regular procedures of realist painting. No longer was representation tied to the instrumentality of diachronic time. Collage belongs to the absence of time, the synchronic dimension. Everything is already there all at once. It’s just a question of organising, or disorganising, what is already there. It’s a question of finding rather than seeking, as Picasso said, of yielding to the caprices of Fortuna rather than struggling to make.

How improvisatory a medium is collage? Do you have a strict sense of what will happen before you start? Improvisatory is not a concept I associate with collage, or at least not my collages. The word makes me think of Jazz (which like Adorno I dislike) with its "pseudo-emancipatory” stringing together of outworn musical cliches into preordained sequences. I have little sympathy for collage or art in general which pretends to embody freedom of self-expression by taking on an “improvisatory look”. Having said that, collage, at its best, is a confrontation with the genuinely unpredictable and with what is beyond any form of “self-control” or “self-expression”. In my view collage comes from elsewhere. The collage artist may seek to take possession of it, but the power of collage comes from its transcendence of selfhood.

John Stezaker. Mask CLXXXIX, 2016. Picture credit: © John Stezaker. Courtesy the artist, The Approach, London; Gallery Sofie Van de Velde, Antwerp; Richard Gray Gallery, Chicago; Petzel Gallery, New York; Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne; and Kaufmann Repetto, Milan

John Stezaker. Mask CLXXXIX, 2016. Picture credit: © John Stezaker. Courtesy the artist, The Approach, London; Gallery Sofie Van de Velde, Antwerp; Richard Gray Gallery, Chicago; Petzel Gallery, New York; Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne; and Kaufmann Repetto, Milan

Collage is often something that most people encounter in childhood, can you remember your first attempt (and how you felt when you created it?) I recently saw one of my very first collages after nearly 70 years, as a consequence of going through my mother’s things after her death. I was surprised that she had kept one of them. They were made with ready gummed papers sold in packs of different colours made just for the purpose of children’s collages in the 1950s.

Seeing it brought back the memory of the taste of licking the fragments of the gummed paper and of the difficulty of getting them in exactly the right place before mounting them because of their stubborn irreversibility. They would stick to one’s fingers. But what they lacked in terms of the control of the overall images, I remember they made up for in the intensity of their colours, which I loved. You couldn’t get that brightness of colour with poster paints or crayons.

What also came to mind was how quickly I would run out of my favourite colour, blue and the need to ration my use of blue. It now seems paradoxical that what at first drew me to collage was the brightness of the gummed papers in the light of the dominantly monochrome nature of my adult productions. In the 1950s collage was not much practised in the kindergarten of that time though I enjoy the infantile association it has now.

There is something inherently playful and regressive in assembling collages and it mirrors the way children use the available detritus of the adult world to create their own miniature worlds. Winnicott’s “Playing and Reality” looks at the role of play in the psychological development of children. I believe his ideas have much to offer in giving insights into the practice of collage and especially into the regressive dimension of this activity.

John Stezaker - Spell, 2022 Picture credit: © John Stezaker. Courtesy the artist

John Stezaker - Spell, 2022 Picture credit: © John Stezaker. Courtesy the artist

Is there a collagist from history that made you realise collage was a thing? Joseph Cornell. I had been making collages since my late teens; so for a couple of decades before the Whitechapel exhibition of Joseph Cornell. I had been aware of Cornell through catalogues, books and magazines a long time before this show in London. But it was only in the encounter with his exhibition that I got the opportunity to see his work in the flesh, rather than just in reproduction.

I am not usually one to spend a lot of time in front of works of art. I am more in the habit of checking things out until I find something that arrests me, and I hardly ever return to a show I’ve seen. But something happened at the Whitechapel before Cornell’s work, which is difficult to relate, I can barely remember what it was any longer. I felt both transported and stilled at the same time. The whole experience was of entering a dream or succession of dreams and coming out of the show was accompanied by a similar amnesia that happens to dreams on awakening.

Perhaps because of this I found myself thinking about nothing else and so returned to see the show not just once but several times. Each time feeling the same sense of having entered a dream world that afterwards I could no longer remember. What puzzled me was, how could images designed for mundane and transient attention found by Cornell could be made to reveal this oneiric dimension, this strange other side. What was he up to?

After several visits I realised I wasn’t going to penetrate this mystery, but there after I read everything I could about him. However, no matter how revelatory and interesting the writers were, including Cornell himself, they got me no closer to grasping the mystery of these tiny works nor to my experience of them. His example gave me the confidence to pursue the image and only the image and to follow my own image fascinations. His lifestyle as a reclusive “exile from life in the world of images” became for me an aesthetic ideal, one that until I retired from teaching I was unable to fulfil entirely, but remained as an ideal. Cornell taught me that images find you, rather than you finding the images, and that the found image for all its ubiquity and everydayness can represent the most profound confrontation with the unknowable.

Is it wrong to think of collage as something ephemeral, or less durable? If that’s true does it concern or maybe attract you? Yes. Just because it is composed of material that is designated for transient consumption should not make it ephemeral itself. On the contrary, the found image is at best an arrest of the transience of turnover and collage an interruption of the process by which the image is absorbed into the momentum of consumption. Most collage work falls victim to the forces which put the image on the edge of disappearance, makes it go away or pass by. I call such work montage and this has become a dominant force in communication and, as a result, in the annulment of the image through its use.

The strategies I employ in my collages are to do with disrupting and arresting these vectors of consumption, though I recognise through the history of collage and the media that these disruptive activities are often recycled by the media as montage. In my work I like to think I am revealing the illegible in the image - what is left when drained of legibility.

I like to see my work as a confrontation with these remains of the image once, through contextual disassociation, illegibility and sometime physical violence breaks the ties with the world of communication to which the found images once belonged. The best collages liberate the image from the flows that make it go away. What remains can be seen as the corpse of meaning, but it is also the point at which the image emanates its own aura of dark fascination.

What’s next for you and what do you think is next for collage? Impossible to predict. I’m never in charge of that no matter how much I try to be. I find that each collage series has its own momentum. It’s a question of allowing oneself to be drawn along by it. I often feel I have had enough of employing a particular collage strategy only to find that the series has not had enough of me. It could just be in the process of putting the work away that something happens to reopen the series.

I have come to see each series as being like a game with particular parameters or rules. Once the variations seem exhausted and repetition sets in, it can feel like it’s time to move on, to change the rule and create a new game. But, the decision to discontinue more often than not itself leads to its resumption. I could never anticipate what’s coming next in my work, even less in what the future might bring for the practice as a whole. Since collage is parasitically dependant on pre-existent media its future is largely determined by changes in the image world and in the nature of image mediation and its technological development.

Vitamin C+ Collage in Contemporary Art, featuring over 100 artists including: Njideka Akunyili Crosby; Ellen Gallagher; Peter Kennard; Linder, Christian Marclay; Wangechi Mutu; Deborah Roberts; Martha Rosler; and Mickalene Thomas is available now. We'll be running more interviews with artists featured in the book in the coming weeks.