Ebay, surrealism and Lorna Simpson

From found footage to dime-store photo booth portraits, the artist’s vintage online finds have freed her to create arbitrary and occasionally surrealist installations

Browsing thrift stores and second-hand websites might not seem like the kind of thing they’d teach you at art school, but, for Lorna Simpson, it’s a vital part of her artistic practice. Simpson found fame with her own photographs, films and installations; yet she is also, as Naomi Beckwith, deputy director and chief curator of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, puts it in our newly updated Simpson book “a consummate eBay scavenger and thrift-store aficionado.”

“Simpson has amassed a collection of, among others things, Black vernacular photography and vintage film reels,” Beckwith goes on. “She is fascinated by the ways in which the materiality of Black history is encapsulated in these orphaned images.”

Simpson has used dime-store photo booth portraits to populate her installations; taken found images as the basis of her collages; and developed whole series from the vintage moving and still images she’s picked up over the years. Our new book focuses on works developed from reels of 1950s promotional footage made for a special-education facility in Wichita, Kansas. Simpson created two films from this found footage, as well as a series of portraits of Barbara, one of the special school’s more senior students.

Chess, 2013. 3-channel video installation, black and white, sound, looped, 10 min. 19 sec., installation view of Jeu de Paume, Paris, 2017

“The portraits start as a study of Barbara’s facial features, glasses and jewellery and quickly morph into a model for all sorts of fantastical interventions that Simpson describes as a ‘shift in imagination’ toward more surreal possibilities,” writes Beckwith.

Though works use the footage as a jumping off point, they don’t really relate back to the subject too closely. Instead, in Beckwith’s view, the arbitrary nature of these film reels gave Simpson “permission to explore other forms and activities that would not have occurred within a strict ordered system.”

A different online purchase led the artist to take off in a different direction. “Yet another fortuitous search on eBay led Simpson to an extraordinary trove of black-and-white snapshots of an African-American man and woman in Los Angeles who staged a series of poses and tableaux,” writes Beckwith. “Simpson’s response was to restage these photographs by recreating the scenarios as faithfully as possible, including hairstyles, clothes, poses, and playing the parts of both male and female figures. This marks a profound shift for Simpson: for the first time, she appears in her own photo work. Heretofore, she had deliberately avoided performing in any projects, understanding – though never fully avoiding – the dual risks of her work being interpreted as autobiographical while at the same time speaking on behalf of all Black women.

“The result is 1957–2009, an installation in which the original vintage photographs and Simpson’s contemporary re-embodiments co-exist,” Beckwith concludes. “By staging these photographs, taken in the years just before she was born, Simpson revives Conceptual photography’s celebrated tendencies toward pastiche and performance. In her recasting, however, photography’s critical interrogations of subjectivity-as-role-play now has a Black figure as its subject and agent.”

In 2013 she returned to this anonymous photo archive to create a three-channel video installation, Chess, copying photographs from the trove depicting the man and woman playing chess.

Yet again, Simpson wasn’t hemmed in by the original source, but instead chose to create a surrealist film, only partly based on her Ebay finds. “She presents the two characters engaged in a match that unfolds over the decades, from the late 1950s to the era of Simpson’s encounter with those photos, a ‘coming to life and into time’ of ideas set out in the initial photography project,” writes Beckwith. “With Chess, Simpson moves out from the register of the historic toward the surreal in terms both of concept and of visual reference.”

Lorna Simpson. Photograph: James Wang

Marcel Duchamp, the pioneering surrealist turned chess devotee, is an obvious reference point here; Duchamp posed for a similar five-way portrait in 1917. By fracturing the point of view in the same way, “viewers must also undergo a complicated, perhaps impossible, process of experiencing the multi-channel Chess project as a gestalt,” writes Beckwith. “As such, the viewer is othered too – our attention is dispersed among the multiple images, the multiple temporalities, the multiple genders. We are spectators of ourselves in the cinematic space, subjects of a surrealist experience of infinite fragmentation.”

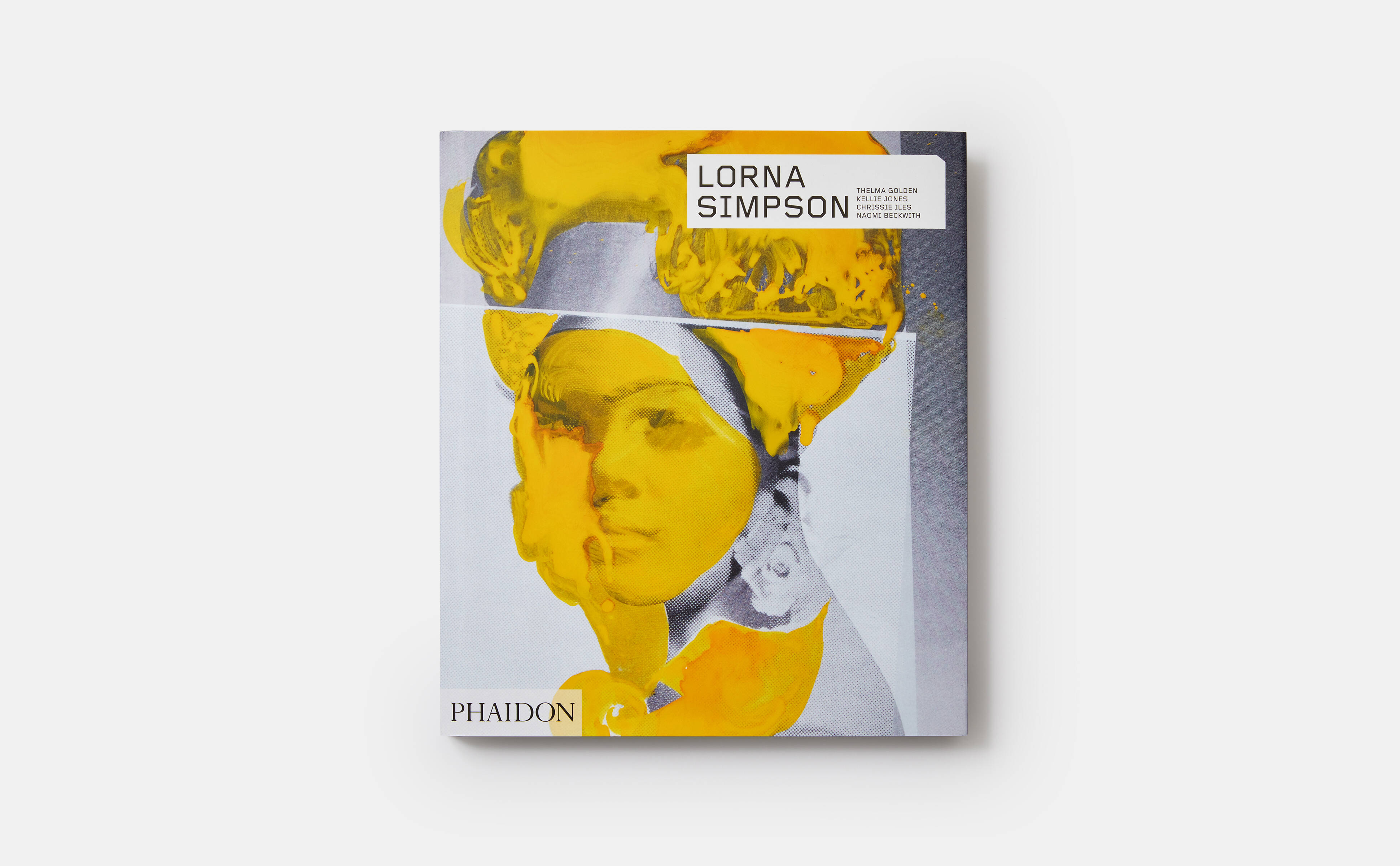

Lorna Simpson

With Simpson, it only takes one successful online bid to conjure up a world of possibilities. To see further images from this great artist, order a copy of our Simpson monograph here.