The unexplained questions in Lorna Simpson’s Waterbearer

The US artist’s enigmatic images and captions aren’t easy to respond to or reconcile

If you know the work of Lorna Simpson, then you’ll probably recognise a Lorna Simpson photograph when you see one. Though the New York artist has worked in a wide variety of media, including collage, painting, sculpture and video, she came to prominence in the 1980s, with a distinctive take on photography.

In our newly updated Simpson monograph, which forms part of our Contemporary Artist Series, the art historian and curator Kellie Jones picks out the key characteristics of a Simpson photograph: “those elegant black female figures, their backs to us, rejecting any familiarity yet communicating with us feverishly in accompanying written messages located just beyond the borders of the image.”

The works first appeared at a time when artists were querying the reliability and treachery of images and Simpson’s work formed part of this interrogation. “Using the traditional format of the silver print, Simpson questioned the authority of realism that defined the photographic project,” writes Jones. “Particularly at issue were the tropes of documentary practice, which in their illumination of human suffering mostly framed such realities as natural, inevitable occurrences, the political causes behind the events remaining invisible and unexamined.”

By way of example, Jones focuses on Simpson’s 1986 work, Waterbearer. As Jones sees it, this picture “might once have been seen as the handmaiden common to many of Vermeer’s domestic dramas or as a classic caryatid of ancient Greece. But the addition of language meant that the work spoke to us simultaneously in different ways and on a number of levels.

Lorna Simpson, New York, 2021

“The figure in Waterbearer strikes a delicate and graceful pose. She holds a pitcher in each outstretched hand. These paired vessels – one silver and the other plastic – seem to mark the endpoints of the economic spectrum. Women of all classes, it appears, face regulation and impediments to expression and power. The text gives voice to women’s language and memory, even while revealing how this speech is stifled and controlled: ‘She saw him disappear by the river, They asked her to tell what happened only to discount her memory’.”

It’s a powerful passage of text, which seems to raise more questions than it answers. “What Simpson does in Waterbearer and in other works from this period is to comment on the lived truth of women in general and black women in particular,” writes Jones. “Yet, embedded in the very structure of the work itself, in this case in the confrontation between the specificity of individual vision and the need of social forces to control what is recorded, is the action of the artist prying into the history of photographic practice, questioning what we see and how we see it.”

We can’t see the photograph, read the caption, and draw one, simple, conclusion; instead, Jones writes, “Simpson works against a seamless, naturalised view of the universe. The photographic truth lies somewhere in the space between the image, the text and our responses to it.”

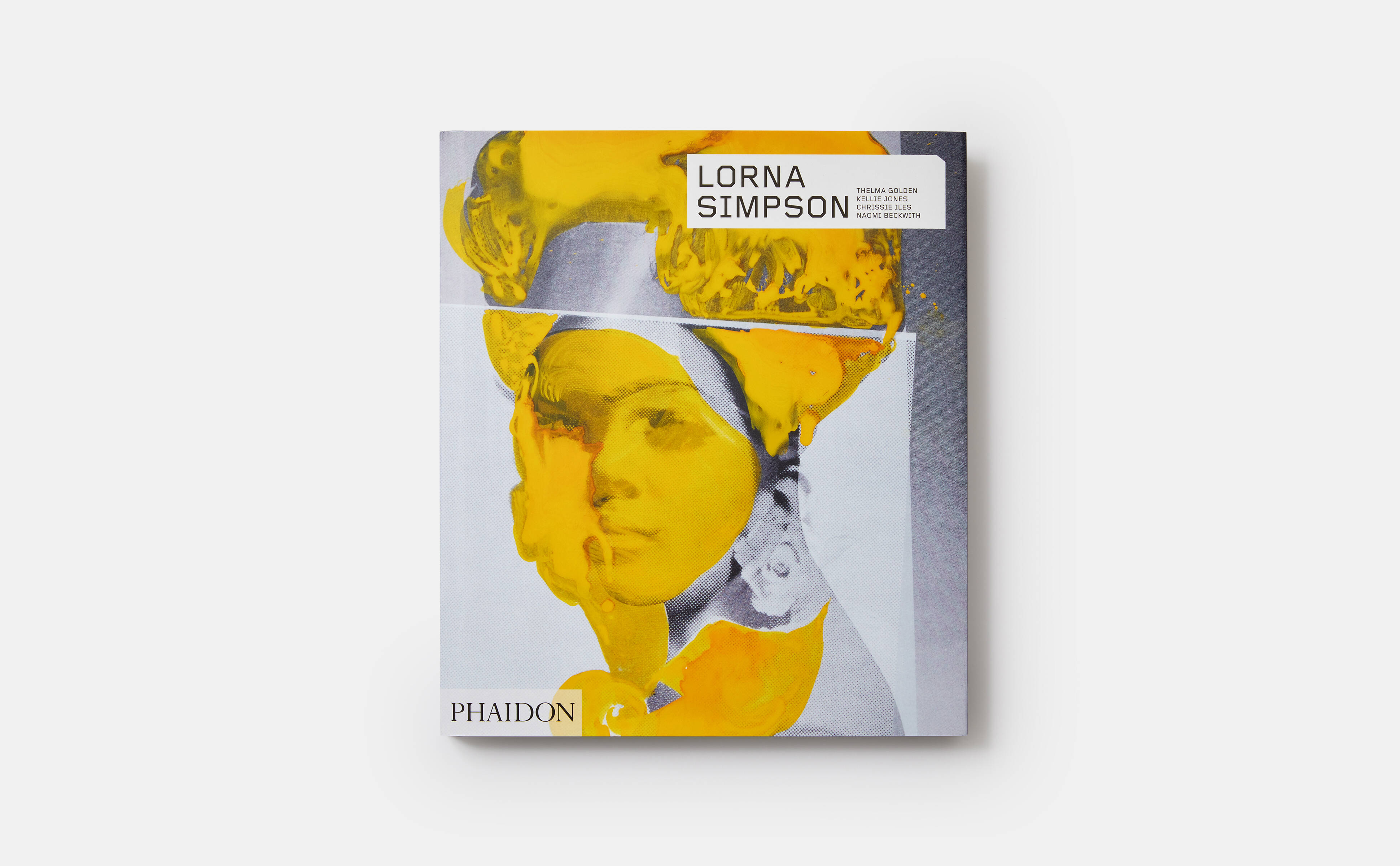

Lorna Simpson

Lorna Simpson

To see many more of Simpson’s work, and to better understand its meaning and effect, order a copy of our new Lorna Simpson book here.