How to view the colours in Faith Ringgold’s Black Light paintings

When the artist engaged with American abstract art she did not leave race relations out of the picture

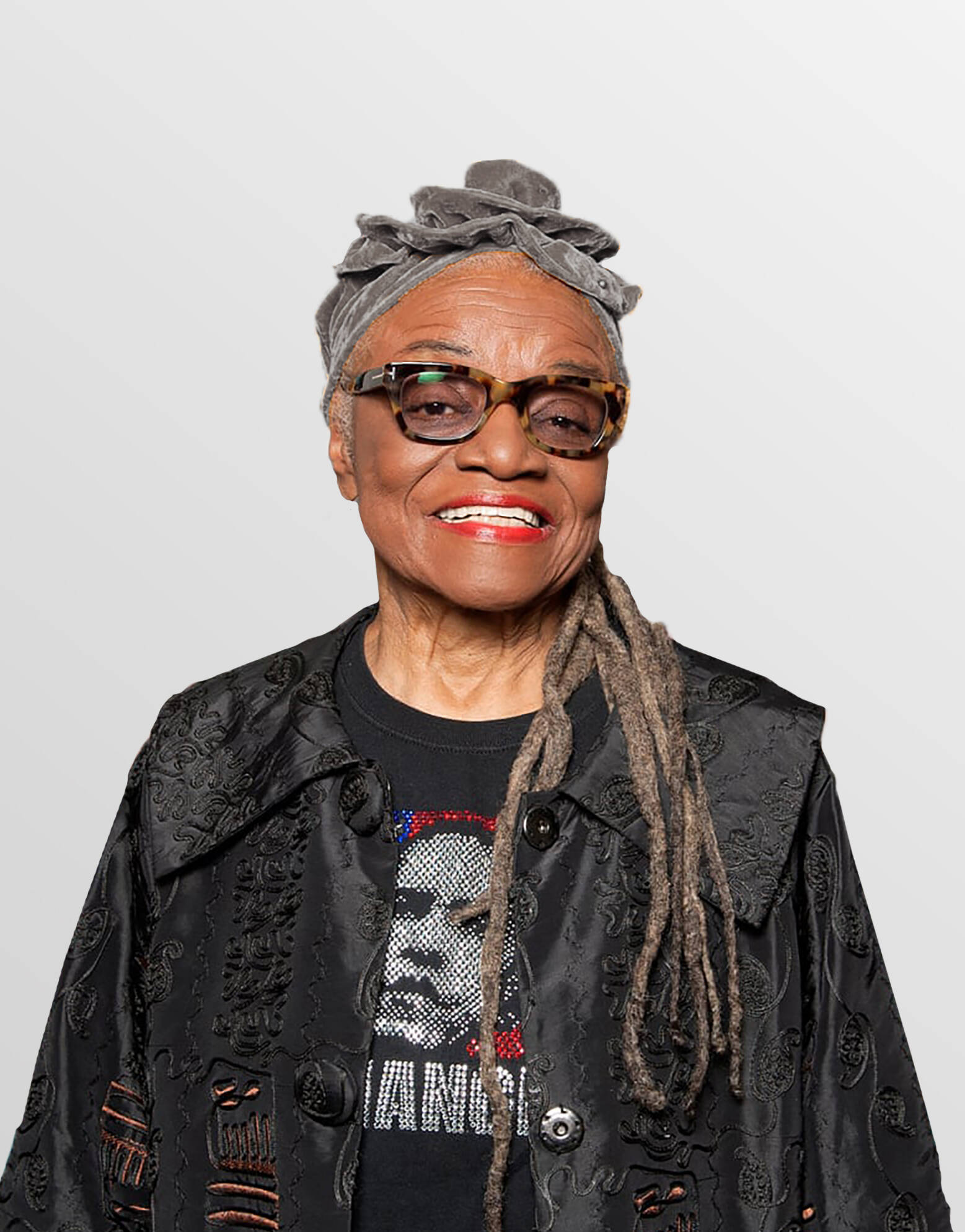

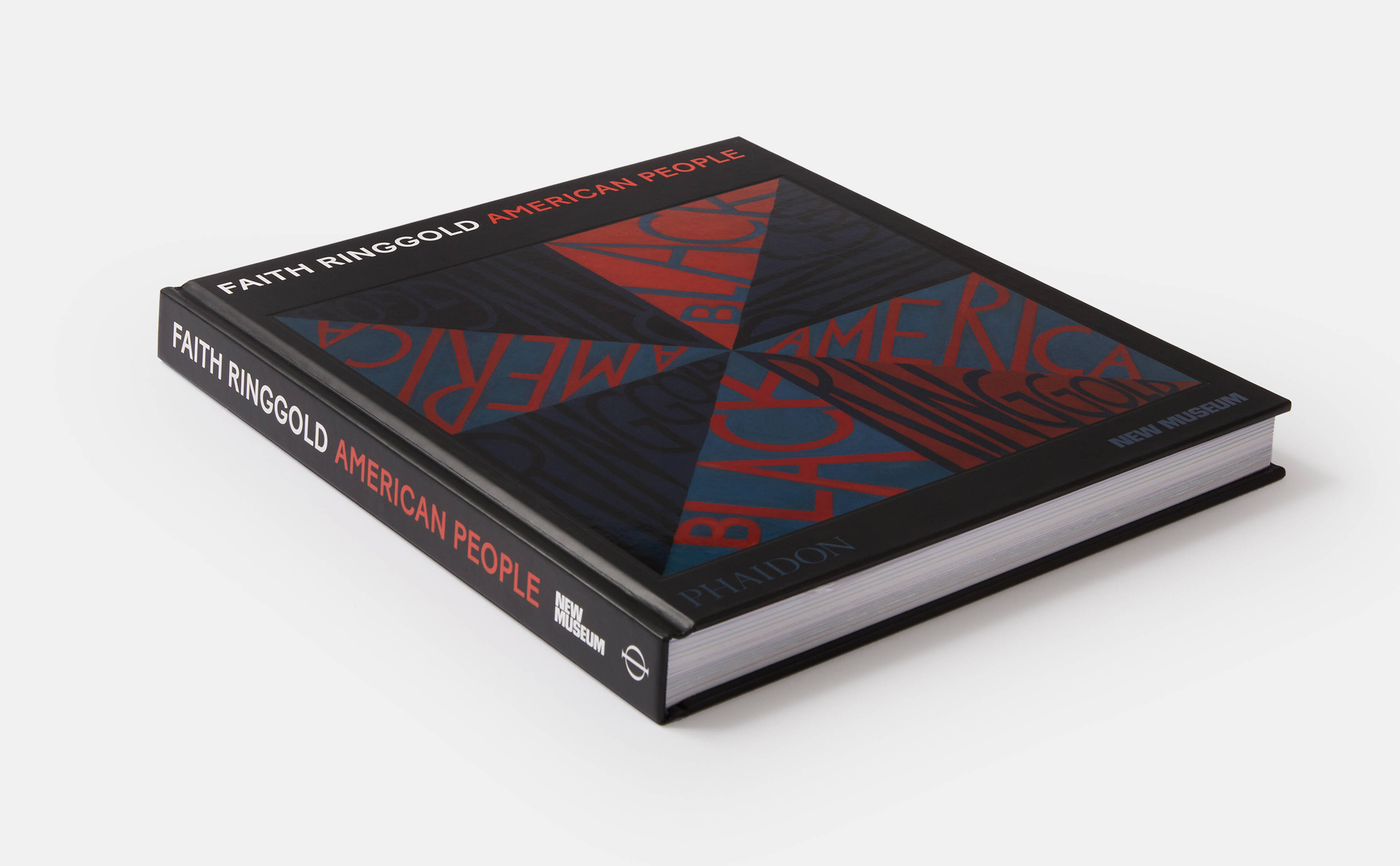

For almost all of Faith Ringgold’s long life, she has been a vital and important American artist. Yet, as the poet and essayist Amiri Baraka points out in Faith Ringgold: American People (which accompanies the artist’s career retrospective at the New Museum), Ringgold’s hasn’t always sat well within the limits of the gallery system.

“Faith Ringgold’s works have existed within the parameters of ‘American Art’ but have never been squashed by the exclusion and denial of reality that American art sometimes is,” writes Baraka. “Faith’s work is not the art of the drawing room, so that you have to ask those coming in and out of the drawing room (the servants) where stuff is ‘really at’.”

During the middle of the 20th century, abstract painting of one sort or another was hugely popular in American galleries. Works by Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, Mark Rothko and Ad Reinhardt inflamed and delighted those within the American art world of that time, while remaining, it seems fair to suggest, relatively disengaged from concerns beyond the gallery walls.

Take, for example, Reinhardt’s black paintings of the early to mid 1960s. Executed in slightly differing shades of black and near black, the works were, Reinhardt once said one such work was “a pure, abstract, non-objective, timeless, spaceless, changeless, relationless, disinterested painting—an object that is self-conscious (no unconsciousness), ideal, transcendent, aware of no thing but art.”

Today, Ringgold is better known for her quilts, books, and figurative paintings, many of which depict black people’s lives in America. Yet in the 1960s, Ringgold was still a relatively obscure artist, cognisant of the trends within the New York Art world. She appreciated and understood Reinhardt’s work, but couldn’t respond to such material herself without bringing race relations into the picture. So, when she created her Black Light series, colour was far from an abstract concept.

“Her Black Light Series was based in part on Ad Reinhardt’s ‘colored’ black paintings,” writes the critic and curator Lucy R. Lippard in our new book, “an ultra-formal idea that she hijacked for her own antiracist ends. At the same time, Ringgold adapted African Bakuba design—eight triangles in a square—precisely ‘to get rid of that up-and-down business’ (the ubiquitous grids of Minimalism) and ‘create a poly-rhythmic space.’”

Faith Ringgold, Black Light Series #7: Ego Painting, 1969. Oil on canvas, 30 x 30 in. (76.2 x 76.2 cm). Art Institute of Chicago; Wilson L. Mead Trust Fund; Claire and Gordon Prussian Fund for Contemporary Art; Mr. and Mrs. Frank G. Logan Purchase Prize Fund; Ada S. Garrett Prize, Flora Mayer Witkowsky Purchase Prize, Gordon Prussian Memorial, Emilie L. Wild Prize, William H. Bartels Prize, William and Bertha Clusmann Prize, Max V. Kohnstamm Prize, and Pauline Palmer Prize funds. © Faith Ringgold / ARS, NY and DACS, London, courtesy ACA Galleries, New York 2021. Photo: Art Institute of Chicago / Art Resource

The first work in the Black Light was created in 1967, the year Reinhardt died; the final work was finished in 1969, a year of enormous cultural and political foment, which saw the moon landings and the assasination of Fred Hampton, deputy chairman of the Black Panther Party. Throughout the series, Ringgold engaged with the American abstract movement, without entirely losing some figurative sense, or distancing herself from the political concerns of the day.

Works such as Red White Black Nigger, and Flag for the Moon: Die Nigger (both painted in 1969) demonstrate her dedication to political causes. Indeed, her flag work led to her arrest, when Ringgold took part in The People’s Flag Show, at the Hudson Memorial Church in New York’s Greenwich Village in November 1970.

Faith Ringgold. Courtesy ACA Galleries, NY

Here’s how curator LeRonn P. Brooks describes the turn of events in our book: “At the opening on November 9, Ringgold could tell that several of the plainclothes men in attendance were undercover policemen blending in with the hip Greenwich Village crowd. Once they were arrested on November 13 and charged with desecration of the flag by the US attorney general’s office, Ringgold, (and fellow artists) Hendricks, and Toche were taken from the gallery by plainclothes detectives to the local precinct and then to the city jail—also known as the Tombs—on Centre Street in Manhattan.”

The charges were eventually dropped, yet Ringgold didn’t manage to garner as much attention from the art world, as she did from the authorities of law enforcement. It wasn’t until 1987 that Ringgold received a solo exhibition in New York’s SoHo, writes Lippard, “then the mainstream’s stronghold.”

The current New Museum retrospective makes up for this oversight to some degree, and ultimately, Lippard argues, Ringgold’s uncompromising position has led to a more consequential career.

“All of Ringgold’s art, even that which appears abstract, is informed by activism,” writes Lippard. “In my opinion, this makes her doubly important. Determinedly marginal and proud of it, Ringgold has persisted and triumphed.”

Faith Ringgold: American People

To better understand Faith Ringgold's art, and life, order a copy of Faith Ringgold: American People here.