The sons of Phaidon reveal how dad helped shape their creative lives

For Father's Day we salute the paternal role within the creative lives of artists, chefs, designers, photographers and architects

How does the creative act of parenting play into the artist’s life? Often the two are viewed in antithesis, but, as Father’s Day approaches, it’s worth offering a ‘papa bravo’ for all those paternal drives that have led towards great work.

The French artist Jean Jullien has such a great relationship with his dad Bruno that he includes an interview with him in his new monograph. Bruno, a public servant, was a patient and loving father, according to the text in the book, always willing to indulge his son’s nascent artistic talents.

“You drew all the time,” he tells Jean in the book, “even on tablecloths when we were out at restaurants. It was your way of expressing yourself, of describing the tiniest routine events. You did this in sketchbooks that you would carry around with you, the ones we would offer you regularly. It was a ritual.”

Jean, in turn, thanks his father for introducing him to a wide range of popular culture. “You, Dad, have always been steeped in what I would call popular culture, whether it be comics, music, or film,” Jullien fils says. “I remember you describing films to us that we were too young to see at the time, like The Shining, Basic Instinct, and stuff like that. I was fascinated by your descriptions, and they helped develop my imagination.”

Leandro Carreira. Photo: Jodi Hinds

For the chef and author Leandro Carreira, food also serves as a vital link between the generations. Beside the recipe for cockle rice In Portugal: The Cookbook, the chef and author writes, “I grew up on the west coast of the Algarve where my father used to collect all sorts of seafood with his friends, from the barnacles on the cliffs to crabs and ultimately cockles inshore of the Praia da Amoreira.”

In introducing the dish, pig’s ear salad, Carreira says, “I remember my dad ordering this dish from an old tavern in our city – chewy, vinegary pieces of meat served with thick slices of cornbread”. In the entry for cured sardines grilled with pine needles he reveals, “this recipe is one I have always wanted to try as my grandmother used to cook this for my father, although I never understood why he liked it so much. But after making this dish, I finally understood. The flavour of the pine needles infusing the fish is simply superb.”

Carreira’s dad also helped with the book’s research, helping his son better understand the delicate, flour-free pudding-like cake, fatias de tomar, which can only be cooked in a special, hand-made stainless-steel steam.

“I sent my dad on a mission to find someone that makes one, and he found an artisan who still makes a few a week,” writes the chef. “It is an extraordinary piece of kit, as it is a special double boiler pan; the result is a light, fluffy cake.”

A young Paul Smith leans proudly on his Paramount bicycle. Courtesy and copyright © Paul Smith

The fashion designer Paul Smith also credits his dad with delivering some impressive bits of kit. In his Phaidon book, the designer covers 50 years in the fashion industry via 50 beloved objects. Two of these – his camera, a Kodak Retinette, and his first racing bike, a Paramount made by Mercian in Derby, England – were given to Paul by his dad. However, the paternal bequest the designer values most is intangible. Beside a black-and-white picture of his dad clowning around with Paul on a family holiday, the designer writes how he truly cherishes his father’s sense of humour.

"My father was brilliant at breaking the ice with people. When we went to a relative’s house on a Sunday, he’d demolish the stiffness and formality of the occasion within a couple of minutes. Maybe he’d have a pocketful of plastic spiders or some of his funny photographs to show round. His character and, particularly, his sense of humour have been very important to me over the years.”

“My dad was something that doesn’t exist any more: a credit draper,” Smith explains. “He travelled round and went to people’s houses to sell them clothes for which they could pay him so much a week. He was almost like a counsellor for some of those people, if they were going through difficulties with their health or whatever. He was a good listener and always very positive. It was his job, but people liked being able to have an honest conversation with him.

“One of the most important things I do is go into one of my London shops for a couple of hours on a Saturday afternoon, not just selling things but also talking to customers. You meet so many people from different walks of life, drawn by the common thread of an aesthetic interest. And you learn about the things that are not right as well as the things that are right."

Catherine and John Pawson. Photography: Gilbert McCarragher

John Pawson also credits his father with shaping his world view. While his mother– the daughter of Yorkshire Methodists – eschewed material possessions, “my father – and I – in contrast, always quite liked the best of things, nice cars, a big old Irish wolfhound for a dog, the best racing bike,” the architect told the Guardian.

Pawson tried to work within the family business – a textiles and clothing concern – and it was his father who, “in a gentle way” pointed out that he wasn’t an ideal fit for the company. At a loss as to what to do next, Pawson decided to head to Japan, having seen a documentary about Zen Buddhist monks. “Being 24, I thought, ‘Oh, I’ll go and be one of those.’ I flew to Japan.” That trip was the first step upon Pawson’s path towards becoming one of the world’s most admired minimalist architects.

Now he has children of his own, he finds their needs shaping his work. Home Farm, Pawson’s beautifully reworked farm house and accompanying outbuildings on the edge of a hamlet in the Cotswolds, was developed by the architect in part to accommodate his three adult children and their families, who like to visit John and his wife Catherine at this country place.

In Home Farm Cooking, John and Catherine’s cookbook, inspired by time they’ve spent at the property, is deeply informed by the wider family. One of their sons is vegan, which means they’ve shifted their focus away from fish and meat; their kids also introduced them to London’s Violet bakery; and its owner, food writer Claire Ptak, contributed a recipe to the book.

“We are a large family,” writes Catherine in one section of the book. “Our grandson was born recently and there are now four generations of the family, spanning ten decades. With friends, there are sometimes twenty people sitting around the Christmas table. The preparation of the food is planned with military precision and everyone helps. In our family the preference is for either goose or roast beef, instead of the traditional turkey, alongside which is a hearty nut loaf, prepared for vegetarians but enjoyed by everyone. The meal stretches long into the afternoon, with games played afterwards and presents unwrapped.”

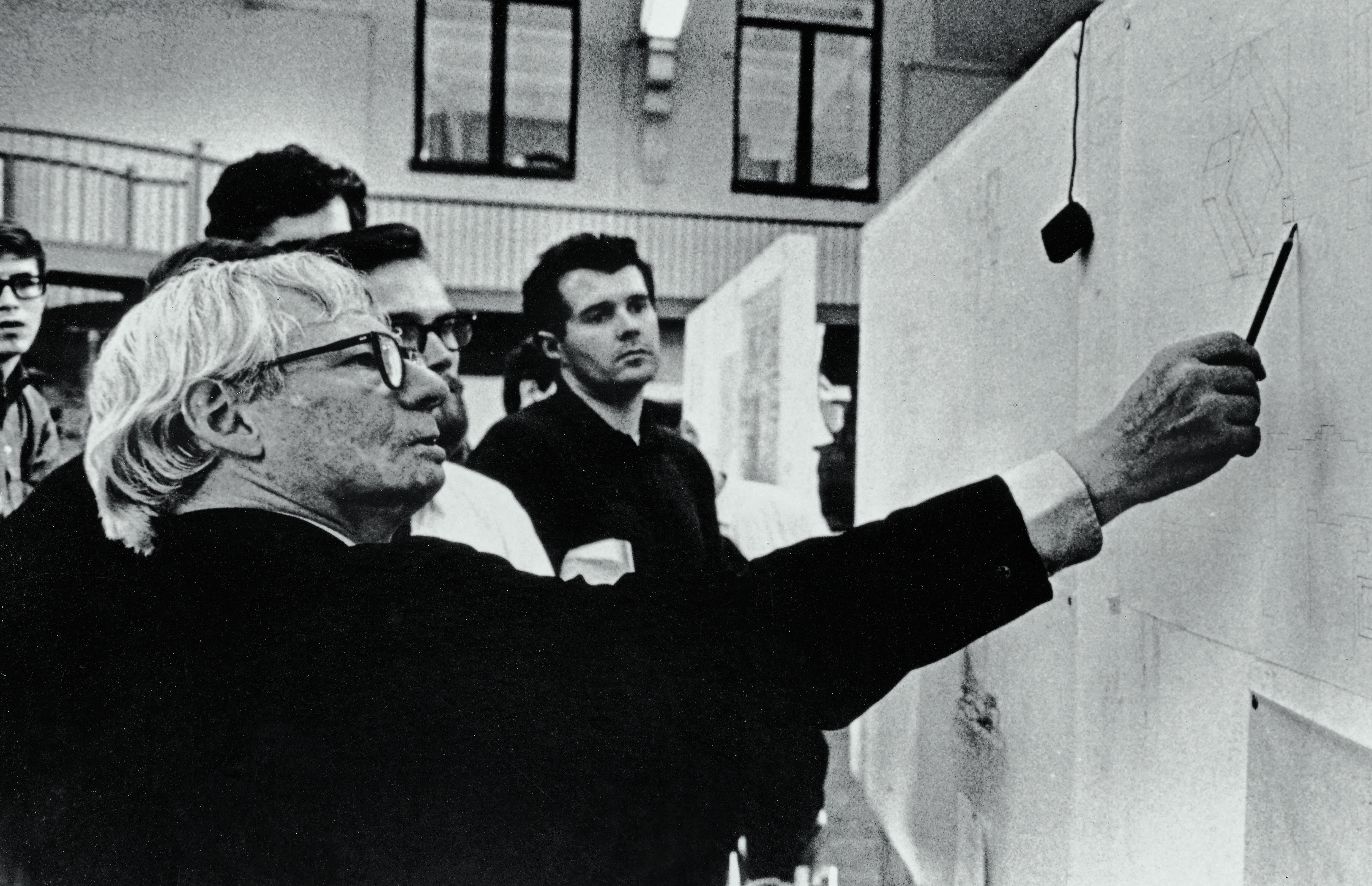

Louis Kahn teaching graduate architectural studio, University of Pennsylvania, USA, c.1967. Photo by Eileen Christelow Collection, The Architectural Archives, University of Pennsylvania

The Estonian-American architect Louis Kahn received a similar gift from his father, Leopold, albeit one which turned out to be a mixed blessing. “Leopold’s beautiful handwriting secured him work as a scribe and paymaster for the Russian army, and it was he who encouraged Kahn to draw from an early age,” explains the author Robert McCarter in our newly updated Louis Kahn monograph. “Leopold also worked as a glass craftsman, both with painted and coloured glass, and Kahn would later develop a particularly powerful sensitivity to light in his own work. The fascination for bright colours was also the likely cause of the terrible accident that befell Kahn at the age of three, when he shovelled burning coals onto the apron of his pinafore. The flames severely burned Kahn’s face and hands, scarring him for life.”

Despite these scars, Kahn flourished both professionally and socially. McCarter’s book describes the architect’s progress, creating libraries, museums and, of course, the great Salk Institute, as well as smaller-scale housing. In these final works, Kahn’s own parenting experience may well have informed his sensitive, modernist dwellings. McCarter focuses on the architect’s understanding that a home needs dedicated spaces for the hard work of home making, which was remarkably deft for the 1940s. “If the storage, laundry and workshop is left out of the plan,” writes the author, “these activities must take place in the living room, kitchen and bedroom of the house, – McCarter adds that this foresight “may also reflect Kahn’s own experiences as a new father and family man, coming with the birth of his daughter Sue Ann in 1940.”

Magnus Nilsson. Photo by Erik Olsson

Khan, of course, lived in a time before Facebook and Instagram – a period the chef and author Magnus Nilsson looks back on with some envy. In his book, Fäviken: 4015 Days, Beginning to End, the chef and author reflects on his career to date, having closed his incredible, award-winning restaurant in 2019. In the section, Blowing your mind in the Anthropocene?, Nilsson considers fine dining, social media, and the way in which our heavily mediated world can limit, misrepresent or stymie some – though not all – experiences.

The 38-year-old chef ponders how much better going to a incredible, out-of-the-way restaurant in the time before the iPhone – an era before we “openly started imposing our experiences on the whole world and depriving our fellow humans of much of the pleasure of discovery that is, and has been, such an important factor in motivating our species into development.”

“There are fortunately a few things that are still impossible to experience before you actually experience them yourself,” he goes on. “Having kids, for example. Even if you have read parenting books and even if your friends have bombarded your Instagram feed with baby pics and heartfelt accounts of what it felt like to receive their little bundle of joy, the feeling you experience when first holding your baby is one that you won’t experience even a little until you are actually there.”

That singular experience doesn’t end when the kids begin to walk and talk. In Joel Meyerowitz’s two-volume monograph, Taking My Time, author Francesco Zanot describes Meyerowitz’s touching documentary (and accompanying limited-edition comic), Pop, which focuses on the photographer’s relationship with his father, Hy Meyerowitz. The 80-minute film was shot in 1995, when Hy was suffering from Alzheimer’s. In the film Joel, Hy and Joel’s son Sasha take a road trip from Hy’s home in Fort Lauderdale to Hy’s old family home in the Bronx.

Pages from Pop by Joel Meyerowitz, as featured in Taking My Time

“The faint hope is that Pop might still be able to recognise the neighbourhood in which he had spent most of his life, that he might benefit from returning to where he was once regarded as the ‘Mayor of the Block’” writes Zanot. The film, which was included as a DVD in early editions of Taking My Time, and is now available to watch online, “is first and foremost the loving tribute of a son to a father,” writes Zanot.

“Hy Meyerowitz is unquestionably the star of this road movie,” writes Zanot, “an eighty-seven-year-old capable of joking in front of the camera with the same defiant spirit he had once enchanted audiences in the Borscht Belt hotels with his Charlie Chaplin imitations.” Ultimately, the key audience for Hy remains his family. Towards the end of the film, Hy reflects on his life, lamenting that neither his mother nor his wife truly understood him or “saw” him.

“He cries, ‘No one saw me,’” writes Zanot. “And Joel replies, ‘We saw you Pop; your boys saw you. Hy finally grasps what his son is saying and exclaims the words that lie at the heart of the film: ‘YOU SAW POPPA!’’ On father’s day, what poppa could ask for more?