RIBA winner Sir David Adjaye on the future of memorials

Following the announcement that the architect is to receive RIBA’s Royal Gold Medal, British architecture’s highest honour, we share some of his thoughts from our new book In Memory Of: Designing Contemporary Memorials

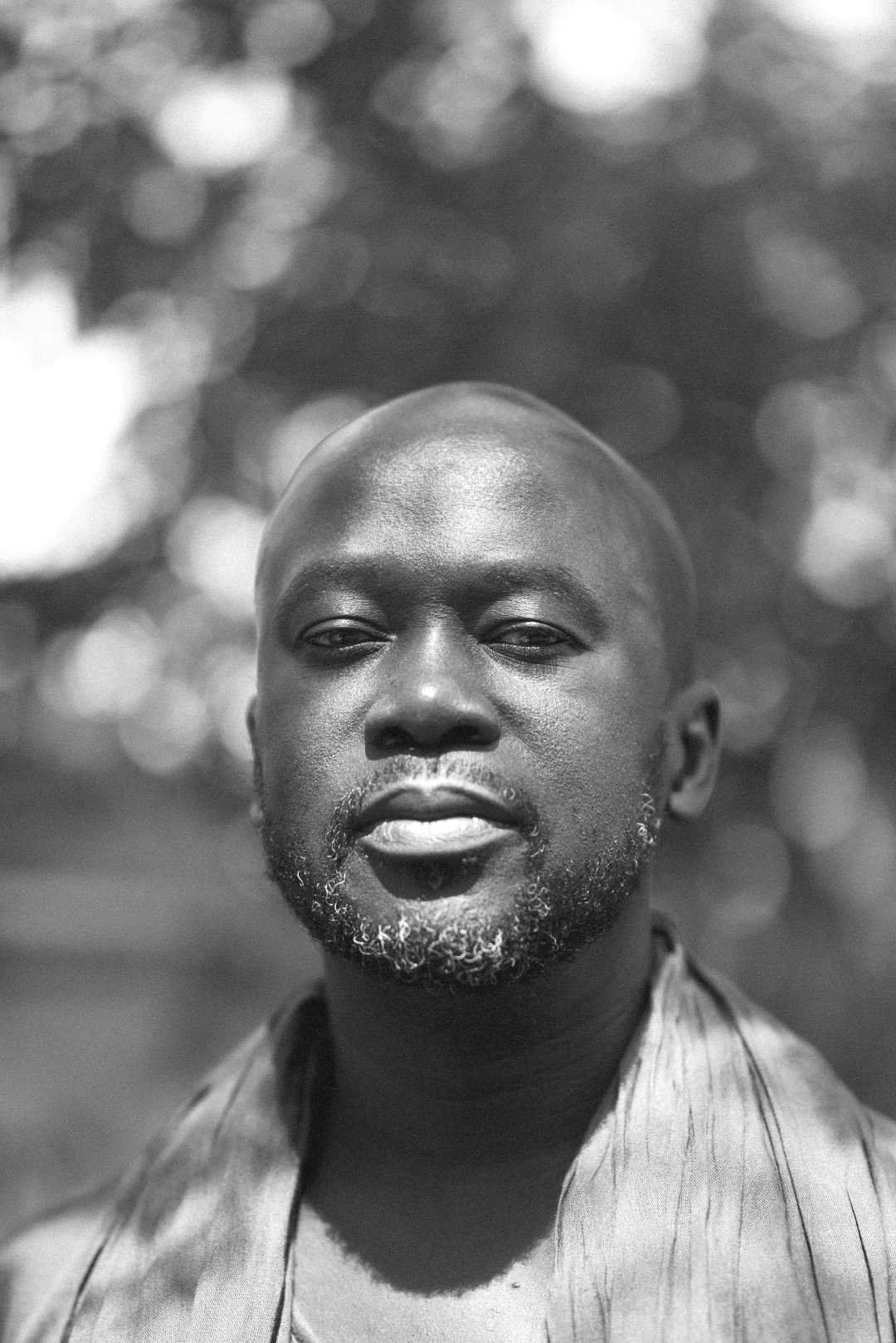

David Adjaye is one of those rare architects who can look forward while also looking back. Our new book, In Memory Of: Designing Contemporary Memorials, features a number of his works, including the Gwangju Pavilion, built to commemorate the protesting students massacred in South Korea in 1980, and the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, in Washington, DC. Both demonstrate how, with innovative, contemporary forms, architects as great as Adjaye can create works that can commemorate the past while remaining thoroughly up-to-date.

So, it comes as no surprise to discover that the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) has chosen to award this Ghanaian-British architect with its Royal Gold Medal, the UK’s highest honour for architecture, and one which is approved personally by Her Majesty The Queen. “Blending history, art and science he creates highly crafted and engaging environments that balance contrasting themes and inspire us all” said RIBA’s president Alan Jones.

However, Adjaye isn’t just a great, practicing architect; he is also a talented architectural tutor and an articulate writer. In the foreword to In Memory Of: Designing Contemporary Memorials, he considers how our new book approaches its timeless subject at an apt point in history.

“This book comes at a time of rethinking spatial storytelling,” he writes. “It is encouraging us to look more critically at the memorials we’ve made in the past, and question the relevance of memorials in the twenty-first century. Rather than the imperialist idea of enshrining a singular view, I am interested in exploring the democratization of the memorial. As narratives unfold and splinter, there’s almost a fracture—or even a certain failure—in the very idea of making memorials. Given the fragility of this terrain, designing monuments and memorials should be borne out of a desire to make architecture that represents our collective consciousness. Personally, I believe in remaking the role of memorials from static objects to dynamic spaces.

“Architecture always has the potential to reflect an experience of time and place. My design for the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture was about creating a living memorial to black life, but also about forming a new urban room for the city so that the building becomes a monument to everyday life within a charged landscape. In the notion of the memorial, the monument is being made. My provocatively titled 2019 exhibition Making Memory, which opened at the Design Museum in London, allowed me to think about the form of memorialization and to explore some of the deeper meanings behind a series of my projects. The focus of my work is not about the changing of space through an object, but about the way in which we can adjust the context and landscape to encourage a more open form of engagement. [Author] Spencer [Bailey]’s writing shares this sensibility.

“Right now, I feel a call to action about visibility and form. The consciousness, nature, and implication of form is profoundly important for architects to understand. With this, the narrative of memorials is a device to project the many things facing people across the planet: nationhood, citizen rights, human rights, climate action. Memorial form is an important act of un-forgetting. I believe this book makes a valuable contribution to the debate about the form of memorialization and the shape that it can take in the future.” To share in Adjaye’s enthusiasm for this important subject, get a copy In Memory Of here.