Philip Johnson, the Glass House, and its dark secrets

Though Mies van der Rohe’s influence is undeniable, this weekend retreat was not without some hidden depths of its own...

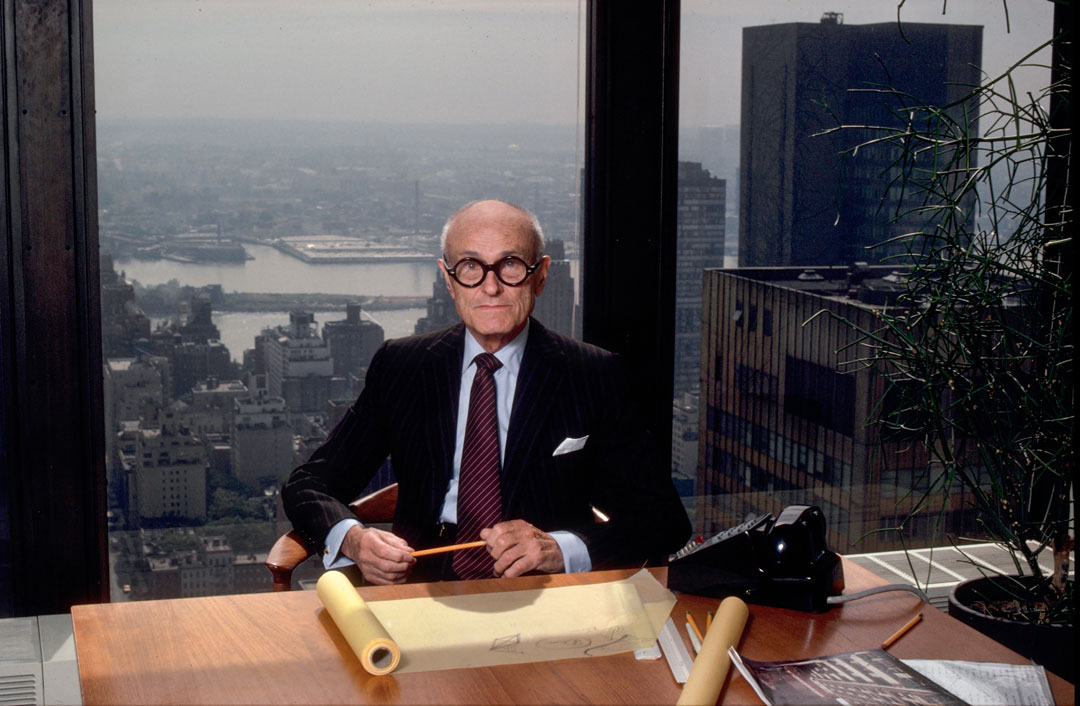

If you wanted to understand the story of American architecture in the 20th century, you could simply read about the life of Philip Johnson. The architect, curator and design agitator, who was born in 1906 and died in 2005, is the subject of our new book Philip Johnson: A Visual Biography and, as its author, Ian Volner says in the introductory text, was a key figure of the period. “In Philip’s absence,” the author writes, “it is unclear whether American architecture in the twentieth century could truly have come into its own, with as much diversity and creative vigour as it did.”

Obviously, there are plenty of landmark buildings within Johnson’s long and illustrious career, yet the best known remains his very own Glass House, the home Johnson built for himself in New Canaan, Connecticut, about an hour north of Manhattan, in 1949.

Here’s how Volner describes the project in our new book. “By 1944—out of Cambridge, out of the military, back in New York, and attempting to launch his practice—Philip began casting around for a country residence, a retreat from the city that could serve as a professional calling card. He had considered settling in Washington, D.C., where he’d done his military service, or perhaps in New Haven, until he saw a site in nearby New Canaan, Connecticut: a 47- acre (19-hectare) parcel below Ponus Ridge, adjacent to its eponymous road. Philip bought it almost on sight, enchanted in particular by a rocky plateau in the middle of the property with a sweeping view ‘almost to New York,’ as his friend John Stroud declared on his first visit. With the help of his graduate school colleague Landis Gores, Philip set about dreaming up the kind of home he might build there and what kind of statement he might make with it.”

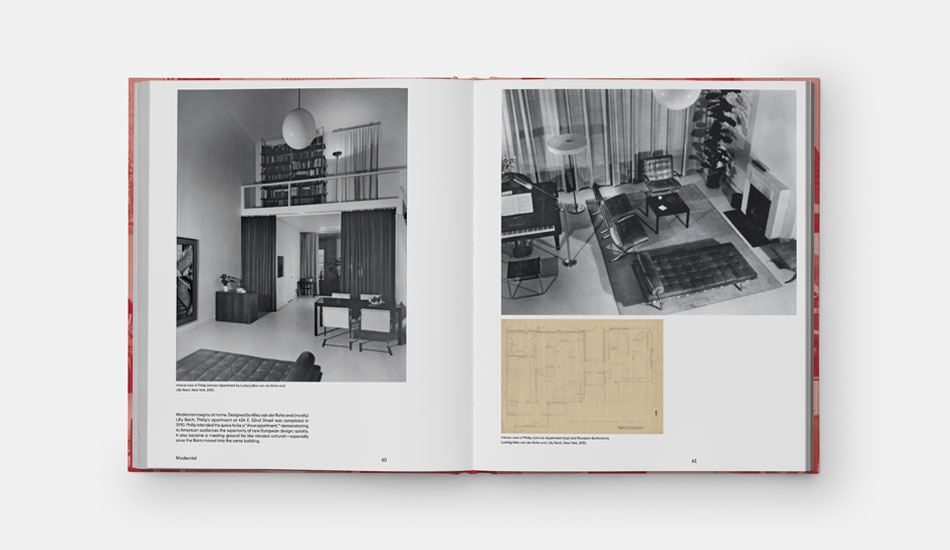

Johnson’s simple, glass-walled home was largely shaped by his great idol of the time, the German architect and erstwhile Bauhaus director Mies van der Rohe. Johnson met van der Rohe in Berlin in the summer of 1930, and soon developed a rapport with the architect. Johnson hired Mies and his then collaborator Lilly Reich to design his private apartment in New York; and Johnson also organized a highly influential 1947 retrospective of Mies’s work at the Museum of Modern Art, which, as Volner notes, “solidified Mies’s reputation as the preeminent European Modernist working in America.”

Did all that admiration assert an undue influence over Johnson’s domestic masterpiece? Some believe so. Mies had been a pioneer of the glass-walled building, a style of architecture largely developed in Germany. Johnson’s Glass House was actually completed a year before Mies’s own landmark, domestic American glass box, the Farnsworth House; and Johnson’s 1947 exhibition even featured plans for the Farnsworth House, leading many to assume that Johnson took more than a little influence from his idol.

Also, as Volner writes, while Johnson’s own simple, economical 1,800 square feet (167 m2) dwelling remains beautifully conceived and austere, the home wasn’t without its flaws. “Though nothing was left to chance, much of its creation was ad hoc: the roof was of simple (and leak-prone) timber, and the corner details do not resolve as neatly as in Mies’s projects,” he writes. Even Johnson himself admitted that it was hard to heat.

Perhaps this explains why van der Rohe did not warm to the Glass House. “Philip’s homage to the recently emigrated eminence was not warmly received by Mies—his first visit ended in a drunken rage.”

Frank Lloyd Wright wasn’t especially taken with the place either; according to Volner, “Wright on entering it for the first time declared that he didn’t know whether ‘to take my hat off or leave it on.’”

Yet this did not stop the Glass House from making Johnson’s career, and popularising the notion of modernist architecture in the United States. “As Gores said, ‘every architecture editor in New York’ paid a call, and through them the house became known to millions who might otherwise have had no conception of what Modernist architecture could mean for the American landscape, much less that it could be so luxurious and romantic,” Volner writes.

“This was Philip’s great coup as an architect, and whatever its functional and aesthetic defects, it was the one work to which almost no one, then or now, could pronounce themselves indifferent. That, after all, was the one reaction Philip never wanted his architecture to produce.”

Socially too, The Glass House served as a great place to entertain; Merce Cunningham staged choreographic works here, and the Velvet Underground even entertained guests, all apparently oblivous to the muted reception the house had received from two architectural heavyweights.

Indeed, Johnson even found a way to take joy in some of the Glass House’s shortcomings. The house’s extreme openness might be read as a one of high modernism’s follies; a design from an architectural fraternity who believed in some imagined, progressive society, where the privacy of brick walls were no longer required.

Johnson didn’t actually see his weekend place like this, and always understood its see-through walls as engagingly problematic. “The idea of a glass house,” Johnson once told an interviewer, “where somebody just might be looking—naturally you don’t want them to be looking. But what about it? That little edge of danger… ”

Besides, this famously transparent house also allowed Johnson to hide some of his darkest secrets, as our new book explains. “The cylindrical brick volume, breaking the simplicity of the steel box, was once likened by Philip to a ruined village he had seen years before;” Volner writes. “He meant, of course, a place he’d seen in Poland during his fascist period. As historian Anthony Vidler once wrote, the Glass House could then be read as ‘a Polish farmhouse “purified” by the fire of war of everything but its architectural “essence”’: an uncanny echo of a dark past, lurking within the familiar icon of American glamor.”

In fact, Johnson used the hearth of his see-through home to expunge the darkest parts of his career. “Following his notorious pre-war flirtation (closer to a full-blown romance) with Nazism, he was careful to cover his tracks, burning the bulk of his incriminating letters and articles in the brick-clad fireplace of his landmark Glass House,” writes Volner.

Like the man himself, Philip Johnson’s Glass House is both famous and recognisable, and, upon closer inspection, a little more complicated than first appearances suggest. To see many more pictures and to learn much more about this building and many others order a copy of Philip Johnson: A Visual Biography here.