The motherly ambition that spurred on Philip Johnson

Philip was the vehicle for achieving his mother’s cultural aspirations, and she poured all of her knowledge and energy into his intellectual formation

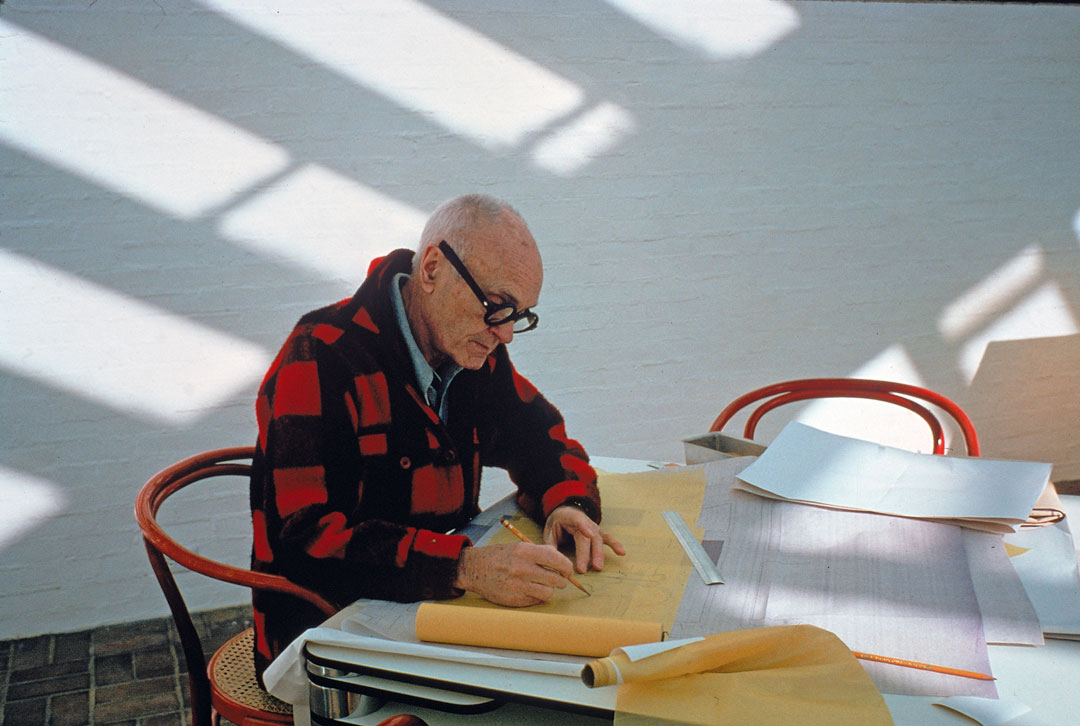

Philip Johnson is, without a doubt, one of the most influential architects of the 20th century. A Zelig-like figure, who was on good terms with Frank Gehry and Mies van der Rohe, Anni Albers and Zaha Hadid, he promoted, influenced and brought together numerous fruitful partnerships; what’s more, his own works, such as his Glass House in New Canaan, Connecticut, earn him his place in the Modernist pantheon. Nevertheless, as Ian Volner puts it in his new book, Philip Johnson: A Visual Biography, the great man is sometimes regarded as “American architecture’s greatest chinwag-exhibitionist.”

He was, of course, a rich, prominent and gossipy man, whose best-loved buildings were often constructed at his own expense; or as Calvin Tomkins put it in his 1997 New Yorker profile,“From the beginning of his career, Philip Johnson’s best client has always been Philip Johnson.”

Much of that wealth came from his family. In the 1920s and 30s, Johnson’s personal fortune, increased hugely, thanks to the rising value of his stocks in ALCO, an aluminum supplier, writes Volner, “soaring far above anything his father had imagined when he gifted them.”

Yet Johnson’s mother also bequeathed another great asset: cultural ambition. As the author explains, Mrs Johnson, or Louise Pope, as she was known before her marriage, “descended from a wealthy Cleveland industrial family, and had gone east to attend Wellesley College before traveling to Europe to continue her studies, a rarity for an American woman in the nineteenth century.

“Her artistic sensibility was as well-informed as it was progressive, and shortly after her (rather late, at the age of thirty-two) marriage to [Philip’s father] Homer, she briefly considered commissioning a new house for the two of them from a still relatively obscure Chicago architect—Frank Lloyd Wright. The project was derailed, but the family home was always a stylish affair, with Louise’s taste guiding the way.”

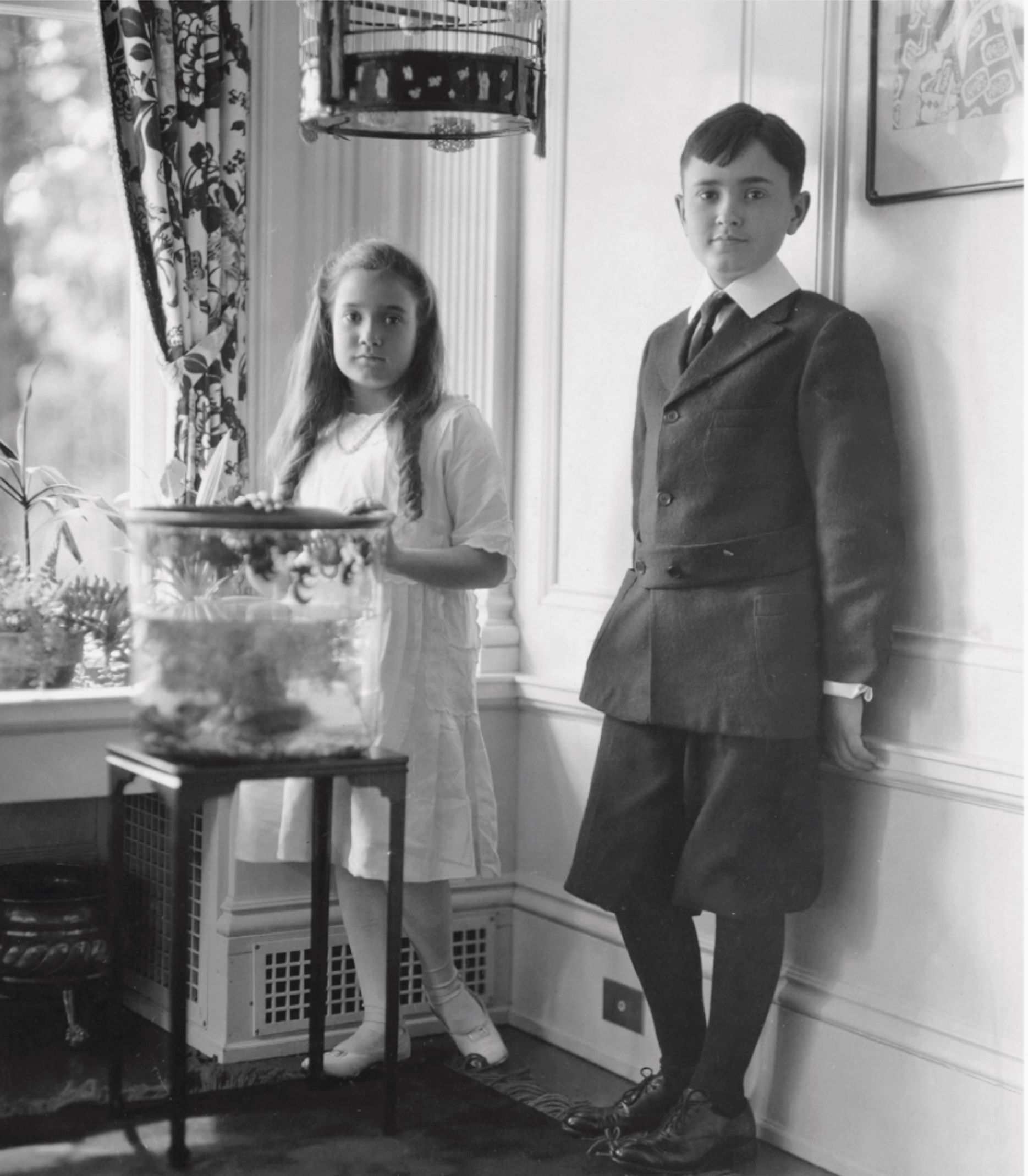

Mrs Johnson would have passed these sensibilities on to all her children, yet an early tragedy in the family prevented her from fully raising her eldest son. "In 1908, when Philip was only two, his brother Alfred—then five—died suddenly of what today would be an easily curable ear infection,” writes Volner. “This left Philip as the best and only vehicle for achieving his mother’s cultural aspirations, and she poured all of her knowledge and energy into his intellectual formation.”

As the eldest boy in the family, Johnson would receive a greater monetary inheritance, but perhaps more importantly, he also may have carried with him greater cultural ambitions, which he would put to good use in his long and fruitful life.

To find out more about Johnson’s formative years, as well as much more besides, order a copy of Philip Johnson: A Visual Biography here.