Philip Johnson and Friends: Andy Warhol

“It was joked about Andy that he would ‘attend the opening of an envelope’ — and so might Philip, if only the name on the envelope were interesting enough"

Many of us see Philip Johnson as prefiguring the twenty-first-century ‘starchitect,’ the boldname designer whose presence adds sizzle to big-money developments. And yet, unlike most of the practitioners who would later assume that title, Philip Johnson’s success did not rest on creating a singular, iconic, and instantly identifiable aesthetic that could then be replicated the world over.

As our new book Philip Johnson: A Visual Biography makes clear, what Philip Johnson sold, at all events, was Philip Johnson.

“In that regard,” argues author Ian Volner, “his was a kind of 'pure' fame, the variety best exemplified by his friend Andy Warhol: Philip was famous for being famous, for keeping company with famous people — people like Warhol himself, who also embodied this new kind of social agent, living his life to the rhythm of flashbulbs."

"It was joked about Andy that he would 'attend the opening of an envelope' — and so might Philip," writes Volner, "if only the name on the envelope were interesting enough." Our new book features a great Christopher Makos photograph of the two kissing at an event in 1979. Sadly, copyright restrictions prevent us from publishing it here.

In what must be a credit to the architect’s capacious intellect the people he found interesting came in infinite shapes and sizes: Isaiah Berlin, Shimon Peres, Barbara Walters, Kitty Carlisle Hart and, yes, Andy Warhol. Philip took them all in, seemingly without fear or favour, and they all returned the compliment. It was in the postwar years, that the sphere that Philip inhabited would dilate dramatically.

“A whole new realm of acquaintanceship opened up to him through his last and longest romantic partner, David Whitney," writes Volner. "While no relation to the museum of the same name, Whitney moved in the most rarified circles of contemporary art, and through him the emerging New York avant-garde suddenly had a conduit to the now nearly sixty-year-old architect.

Whitney was Andy Warhol’s personal confidant (“We were [like] two lonely widows,” he said of the artist, speaking of their shared sense of isolation) and a fairly ubiquitous figure on the New York scene.

Along with Warhol, Lou Reed, John Cage, and Merce Cunningham all became intimates, at least by proxy, and various of their collaborators and hangers-on would put in at least cameo appearances at Johnson's Glass House.

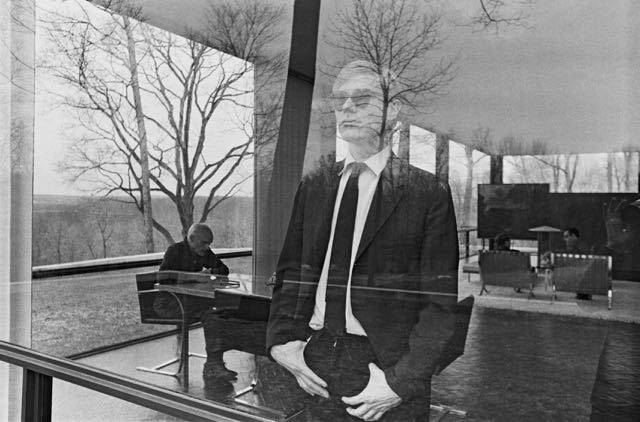

"Nothing else was as much of an asset in Philip’s social dealings as the New Canaan, Connecticut, property, a place everybody knew about but only a privileged few were able to visit in person," Volner writes. "The events that Philip staged there were the stuff of legend, and the great and the good would flock there to see and be seen—and to see the house, a celebrity in its own right." (Even if Warhol’s concerns were of a slightly more down to earth nature.“People always ask me, ‘How does he go to the bathroom in that place?’” the artist is quoted as saying.)

Warhol’s influence on Johnson was reflected in the art Johnson collected and even, at times, the manner in which the bespectacled guru-like figure doled out pithy quotes such as “I am a whore” or “Architecture is the art of how to waste space.”

However, one project on which the two collaborated, did not go as perhaps either would have wanted. "In tandem with his New York State Pavilion project for the 1964 World’s Fair, Johnson was responsible for wrangling pieces from a slew of contemporary artists to adorn it - a tricky proposition, only grudgingly accepted at the last minute by fair organizer Robert Moses," Volner reveals in the book.

"The most contentious submission ended up being Warhol’s 13 Most Wanted Men, a silvery montage of assorted criminals then wanted by the New York Police Department.

“It just had something to do with New York and they paid me just enough to have it silk screened,” Warhol said. The authorities cried foul, obviously concerned it would tarnish the state’s image and the work was painted over (in silver paint, no less) before the fair opened."

For more on Johnson’s social side, his lasting architectural legacy, as well as some incredible stories about the artists and socialites he attracted, get a copy of Philip Johnson: A Visual Biography here.