INTERVIEW: William Hall on why the future of architecture is set in Stone

The author of the latest book in our Building Materials series believes Stone is hard to beat in a climate emergency

William Hall understands that everyone, secretly, is an architecture critic. His Building Materials series of books present concrete, brick and wood structures in such a way as to undermine a casual reader’s architectural prejudices and expectations. Concrete includes many graceful, organic-looking and plainly beautiful buildings; Brick goes far beyond simple houses, to take in the ziggurats of Mesopotamia and the cathedrals of northern Europe; while Wood proves just how limber timber can be, slipping into contemporary architecture as well as it dovetails into vernacular buildings.

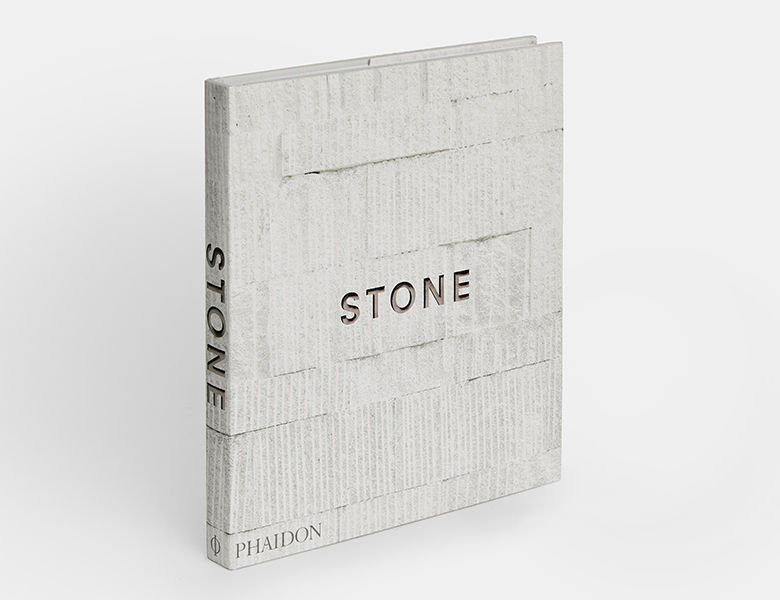

In Hall’s new book, Stone, the author, designer and architecture enthusiast carried out this feat for a fourth time, uncovering a rich seam of rocky buildings, before chipping away at a long list of 6,000 structures, to present a perfectly formed collection, which runs from prehistoric edifices through to recently topped-out creations.

While the oldest inclusions show just how enduring a building substance stone truly is, the newer ones demonstrate that it is, in fact, more than fit for future cityscapes. As Hall says in this interview, stone is not an anachronism; it has a real role in the future.

Why do you think the Concrete, Wood, Brick - and now Stone - series of books are proving such a hit? These books give you a really extraordinary overview of what is going on in architecture related to a particular material throughout history and today. I think of them as a gateway drug to the rest of Phaidon’s books. These are the books that I wanted when I was 18 and a graphic designer who was more into architecture than graphic design. Back then, books on architecture were either tomes about the history of architecture that were a little bit inaccessible, or they were single company monographs where there was too much detail about one architect and I didn’t know which architect I was interested in.

__Why stone (as opposed to say glass or steel?) __ I think it’s useful if there’s some sort of polemical aspect to the books. With Concrete that was very clear. It was about re-presenting a material that had been denigrated. When you ask someone in the street about concrete buildings they think about rain-stained social housing. It’s got these miserable associations, and, of course, the reality of concrete is that it’s one of the most important building materials of the twentieth century and has this wealth of import in architecture.

Brick was another straightforward polemic: brick is pervasive and ubiquitous, but we don’t notice it. It tends not to be used for important buildings and yet there are some really amazing examples. With all of these books I’m interested in eking out the creativity in materiality and demonstrating that, while it is easy to have a fixed sense about a particular material, it can actually have incredible potential.

So what's the polemic with Stone then? When one thinks about stone architecture it’s easy to think of classical or neo classical temples or structures of great importance. We think of it as an historical material, but actually the reality is that architects today are using it in new inventive, creative and breathtaking ways that are really thrilling. And, in addition to that, because the embedded carbon that is the full life cycle of a material – its extraction, transportation, application, and use – is significantly lower in stone than it is for example concrete or steel, it’s pertinent to the climate emergency. So I feel that stone is not an anachronism, it is the future, and it has a real role in that future.

Give us an example of that in action. Well, one interesting example is the one I mention in the introduction to the book, 15 Clerkenwell Close, by Amin Taha. That has a completely stone structure. The project is on the site of a Norman convent which was built with stones from Normandy. He decided to source as close as he could get to the original material. While working with the stonemasons Taha realised there was an ecological aspect to working in that material. He calculated that it was a quarter of the cost of building in steel and concrete.

How do you go about the edit of projects initially chosen for inclusion? The challenge is there are over 150 projects in each book and if I just lined them all up it would be completely overwhelming. I knew from the beginning of the series of books that we had to have some system of breaking them down into kind of perceptible chunks. The chapter names that do this – Form, Texture, Juxtaposition, Landscape, Light, Mass, Presence and Scale - are consistent across the books.

With this book I’ve looked at over 6,000 stone projects, using the Phaidon archive, visiting libraries and trawling the Internet. That was then whittled down to a shortlist of about 350 projects I thought could make the book. From there I got to 200 projects and then I started to distribute them between the various categories. At the start that can feel arbitrary but by the end of the process those pairings start to feel impossible to move.

I’m always looking for a variety. The Parthenon is in this book but I could have had 100 great temples but that wouldn’t have made for a very interesting book. So all the other temples are disqualified as soon as that one goes in because I want the best of each example. So the categories get filled up in an even way and the categories are really important in helping to appreciate the different qualities of the material.

Give us some examples of the entries under Landscape. So for example with landscape some of these projects feel like they’re actually a part of the landscape. The Church of St George in Ethiopia is extraordinary and it’s dug out of the ground. So that is literally of the landscape. Then there are other examples like the City of Culture in Galicia by Peter Eisenman where there is a manmade landscape but it has qualities of a physical landscape, it has topographical ambition. And then there’s the example of Casa Das Mudas Art Centre by Paulo David where you have a sort of artificial landscape, but it still feels more like a landscape than a building in a sense. Then there is Monsanto, a village in Portugal, where there is no escaping the fact that the landscape has influenced the architecture.

Plus there's the odd surprise. Fallingwater, for example; people tend to think of it as a concrete building - because it’s got these incredible huge floating cantilevers - but it’s actually built on bedrock. It also has stone columns that hold the whole thing up so it’s very much a stone structure as well.

Because they are so easy to read people often mistakenly think these books are easy to make don't they? Yes! It’s really difficult for me to express just how difficult it is to do these books. You look through them and you think well, what’s so difficult about that? But in order to write 100 words on even a car park toilet I have driven past it repeatedly on Google, I’ve read everything there is to read on it, I’ve considered the use of stone in its creation and where that stone has come from. I’ve done all this research to write 100 words.

What were the buildings that surprised you along the way? One of the thrilling things about making these books is getting the opportunity to present or represent buildings that are not well known but should be because they’re fabulous. One example is the St Pious church in Lucerne, Switzerland, by Franz Füeg. This is a building that on the outside appears to be a warehouse on a concrete dais. It’s got a steel structure and what looks like from the outside to be white panels all around it.

When you walk inside however, you realise these are made from 28mm thick marble, and the light shines beautifully through them. So you step inside and you’re in a transcendent white filled experience. You feel like you’ve somehow stepped inside a lightbox. There’s a kind of filmic sequence to the panels which seem to me to elicit the process of metamorphic rock being made. It feels like you’re watching a film of the production of marble being made. It’s an incredible building, very special.

So where is stone going right now? In England. There are two aspects aren’t there? One is the English disease of looking back and imagining that the past was better. And there’s also the kind of more liberal forward thinking philosophy of authenticity. I think when you have a building where the structure is stone that does confer authenticity. The weight and the strength is palpable.

I think that the earliest projects in the book used stone as a structural element. But the later projects are increasingly just cladding. Stone is there as decoration and what architects are doing with stone cladding is trying to confer some of the qualities or historical references of the material – grandeur and quality.

A desire for authenticity in an inauthentic era? That's an interesting way of looking at it. I think now with the ecological aspect, increasingly architects are looking at the possibility of stone being used as a structural material again. And I think that’s where the growth will come. We could be on the beginning of the curve. But I don’t think it’s very well known or understood yet. I think part of the reason for that is cultural.

We know what ‘good architecture’ looks like – it’s concrete! And it has clean lines. I think people think of concrete as being a modern unpretentious material whereas they don’t think of stone in those terms, they think of it as expensive, while actually some stone can be really economical in comparison to concrete. That’s little understood at the moment but I think it will change.

I feel that the conversation about the embodied carbon in relation to the climate emergency – that isn’t spurious, that’s real science. There are real facts behind why stone has an important place in the future of architecture. And I know that architects really like these books because I’ve met a lot of them. If I can make architects reconsider stone as a potential material then I’m having a role here.

For a closer look at this material's ancient history, and its spectacular present, order a copy of Stone here. You an also buy all of Hall's books as a special offer in our Building Materials collection here or buy them or two: Concrete, Brick and Wood.