The making of Mid-Century Modernism

How did one style of architecture spread right across the globe? Through adaptation, argues Dominic Bradbury

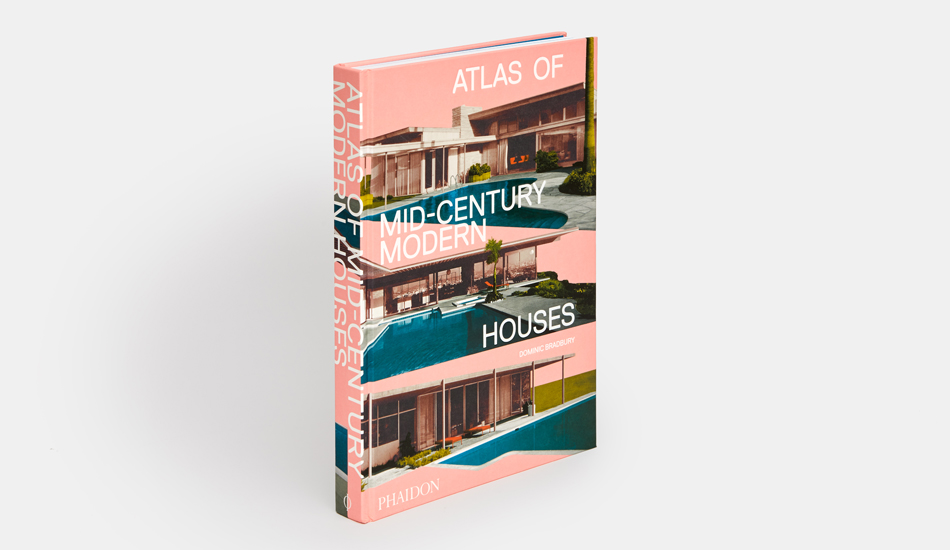

If you think the sparse, simple homes of the mid-century modern period look minimal, you should bear in mind what came before. In much of Europe and East Asia, World War II had reduced the housing stock to rubble. This is partly why Dominic Bradbury, in his introduction to the Atlas of Mid-Century Modern Houses, describes the mid-century period as marking a new beginning.

“The global destruction, displacement and violence brought about by World War II gave way to a period of reconstruction in Europe, Japan and other parts of the world that had suffered during the years of conflict.

“The United States benefitted from the arrival of many highly influential architects and designers, who had fled the rise of European fascism during the late Thirties and had settled in the country,” writes Bradbury. “Among them were a series of pioneering Modernist architects who had once taught at the Bauhaus, including Walter Gropius, Marcel Breuer and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. Importantly, they began to teach in the US (at Harvard and the Illinois Institute of Technology in Chicago) and helped to inspire younger generations of American architects – but they also began to practice there, designing houses and other projects throughout the mid-century period. They brought with them the principles of the Bauhaus and early Modernism but adapted these lessons to the American context.”

We owe many of the tenets of mid-century modern architecture to Gropius, Breuer and Mies, as well as their Swiss-French counterpart Le Corbusier, as well as technical developments that allowed more ambitious structures to be built on domestic plots.

“Steel- and concrete-framed structures obviated the need for load-bearing brick and masonry walls, allowing for more fluid layouts within the home,” writes Bradbury, “and the use of ‘curtain walls’ offered a greater sense of transparency than ever before. Within these more open and flexible floor plans, architects made increasing use of ‘service cores’ holding bathrooms and utilities. Increasingly, the borders between inside and outside space were eroded, creating a more vibrant sense of connection with the surroundings and encouraging the growth of porches, verandas and terraces.

Not every decade covered in our new book – which runs from the end of the war up until the early 1970s - is the same, just as the architecture itself changed and evolved to suit different climates, materials and cultures around the world.

“If the Fifties were dominated, more or less, by single-storey pavilions, compounds and pinwheel plans – as well as floating forms – then the houses of the Sixties gradually became more sculptural and expressive,” Bradbury explains.

“in California, émigrés such as Richard Neutra and Albert Frey combined the precepts of early Modernism and the International Style with the benign context of the West Coast climate,” he goes on. “The resulting ‘desert Modern’ houses made full use of the curtain wall, linear forms, flat roofs, fluid spatial layouts and banks of glass while opening up to the landscape with ample provision of enticing outdoor rooms and terraces.”

Meanwhile, on the far side of the Atlantic a different style was adopted. “Nordic design became associated with ‘soft Modernism’, infused with a sense of warmth and welcome that came from its focus on natural materials and textures, such as timber and stone, as well as an all-important emphasis on the hearth as the heart of the home,” he explains.

A similar approach was adopted in Japan, albeit with different results. “Many Fifties and Sixties Japanese houses explored a passion for crafted spaces in a natural palette, as seen in the work of architects such as Masako Hayashi and Junzo Yoshimura,” writes Bradbury. “But others – including the Japanese Metabolists – began moving in a different direction, exploring prefabrication and modular housing as a way of building new homes more rapidly while feeding the Japanese appetite for fresh buildings. In Tokyo, especially, land itself held the greater value and houses tended to be replaced every twenty or thirty years (leading to the demolition of some wonderful mid-century residences).”

In Latin America, meanwhile, a different style emerged. “Furniture designers such as Sergio Hernandez and Joaquim Tenreiro produced exceptional work, while architects such as Lina Bo Bardi, Sergio Bernardes, Rino Levi, and, of course, Oscar Niemeyer created architecture that was original, innovative and contextual,” writes Bradbury. “The same can be said for Mexico, where Luis Barragan became one of the great figureheads of the period but many others – such as Francisco Artigas, Augusto Alvarez, Jose Maria Buendia, Felix Candela, Max Ludwig Cetto and more – added to the wealth of the country’s architectural output during the Fifties and Sixties.”

No one would mistake a Barragan home for a Nordic one, or a Metabolist city house for a work of Californian desert modernism. Nevertheless, every home in the book captures something of the look and spirit which, Bradbury argues, lives on in today’s domestic culture.

“That’s true of their innovative approach to architecture and spatial planning but also of the expressive nature of the interiors themselves, which are infused with a spirit of positivity, confidence and delight. As such, they remain a vital source of inspiration for twenty-first-century living,” he wrties.

To see that source of inspiration in full, order a copy of the Atlas of Mid-Century Modern Houses here.