What the Notre Dame fire taught our author about stone

As William Hall watched the Parisian cathedral burn he realised the durability of this ancient building material

Our author William Hall has a brilliant understanding of contemporary architecture and design, having written a series of acclaimed titles, Wood, Concrete and Brick, and having worked with such leading figures in the field as John Pawson, the Museum of Modern Art in New York, and the Tate in London. However, it was an encounter with a much older institution in another European capital that made him rethink his take on his latest subject.

“I was in a cafe within sight of Notre Dame when it caught fire on 15 April 2019,” he writes in the introduction to his new book Stone. “Sirens began converging on us from across Paris and tall flames engulfed the roof as a dumbstruck crowd gathered. Watching the apocalyptic vision at its height – as Viollet-le-Duc’s spire cracked and fell hard through the stone ribbed vault – the entire structure seemed vulnerable.

“By morning it was clear that while the medieval timbers of the roof had burned, the stone structure had substantially survived intact. It was the clearest possible depiction of the fireproof nature of masonry. Photographs of the interior completed the picture: 850 years of defiant stone architecture desecrated by timber embers.

But in the world of masonry, Notre Dame is but a young upstart, Hall writes. "The earliest examples of arranged stones are the oldest surviving human spaces and there is evidence for hominins living in stone structures over a million years ago. Our relationship with stone predates even our own species."

Despite its prehistoric pedigree, good stonework was also an early sign of an ordered, ambitious civilisation. “It takes a society with hierarchy and sophisticated organization to extract, shape and arrange stone. It also takes time, manpower and tools. But the payoff is spectacular: fire, wind and waterproof structures. Permanence was only part of the equation – stone encapsulated an utter and heroic mastery of the natural world. Many of the world’s most significant, revered, influential and memorable structures are built with stone, not least Stonehenge, the Pyramids and the Parthenon."

However, Hall also realises that stone is about the future as well as the past, and if we want to avoid raising the temperature to a flashpoint in the future, we need to look back towards the material. “Buildings and construction account for 39 per cent of global carbon dioxide emissions. Emissions for concrete used for loadbearing structures and columns is significantly higher than stone alternatives: marble emits about 66 per cent of the carbon, sandstone about 38 per cent.

“It is easy to think of stone as an unwieldy, expensive, historical material for imposing temples, elegant bridges and grand civic edifices," he writes. "In fact it has unexpected modern efficacy. Quite apart from its inherent naturally occurring variety and beauty, architects working in the twenty-first century are finding that stone represents opportunity and potential. Stone isn’t an anachronism, it is the future.”

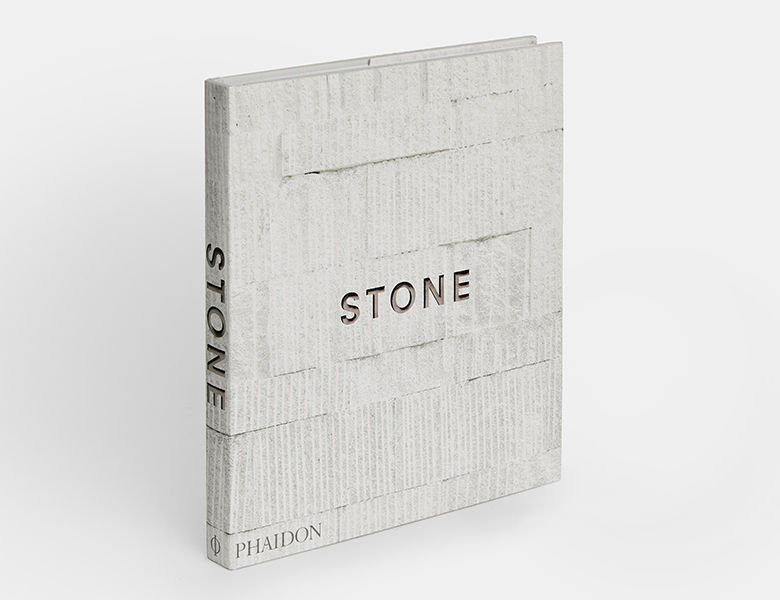

For a closer look at this material's ancient history, and its spectacular present, order a copy of Stone here. You an also buy all of Hall's books as a special offer in our Building Materials collection.