William Hall talks about the new mini format Brick

'The smaller format lets the quieter projects stand out' says the author of Concrete, Wood and Brick

“I was once in Milwaukee with Frank Lloyd Wright, attending a conference there. He began: ‘Ladies and gentlemen, do you know what a brick is? It’s trivial and costs 11 cents; it’s common and valueless but possesses a peculiar characteristic. Give me this brick and it will be worth its weight in gold.’ That was the only time I had heard in public, stated clearly, what architecture really is. Architecture is the transformation of a worthless brick into something worth its weight in gold.” - Alvar Aalto

We were reminded of Alvar Aalto's quote (above) when we sat down for a chat with William Hall. William is the author of our best selling books Concrete, Wood and Brick which we re-publish in a new, mini format this week.

Talking to him it’s obvious that Hall feels the same way about a humble building material he believes is overdue for rehabilitation. His idea to write a book on the humble brick however was not inspired by Aalto's tale but (partly) by a conversation with Spanish super chef and fellow Phaidon author, Ferran Adrià.

“I remember talking to Ferran and him saying that he didn’t have a preconceived notion of the hierarchy of different foods," Hall told us.

"To him, a pear was just as valuable as a lobster, the difference is that we load all these societal and cultural associations on the latter."

It's true that in terms of what we might call high architecture, or significant buildings, brick tends to play the role of poor cousin to more lofty materials such as stone, granite or marble, materials seen as valuable because of their visual qualities or because they are expensive to extract. After all, brick is essentially earth, possibly the humblest thing imaginable.

Brick's great success as a vernacular material - as a material for buildings not made by architects but by builders - has meant that, generally speaking, the important structures of the 19th and 20th century, the ones trying to make a statement about how important they are, have usually been made from something else. Brick not being, as Hall puts it, an ‘appropriate’ material.

“Yet Frank Lloyd Wright had a sense of the value of a material beyond the generally perceived notion. And, of course, he built widely in concrete and brick," Hall says. Which is why the new version of the book is so welcome.

“The new mini format, isn’t just a facsimile of the original,” says Hall. “In the original version most projects are seen as pairs on a spread. Those juxtapositions can be challenging and informative. The smaller format doesn’t have room for two projects together so the quieter projects stand out.”

Despite its diminutive size, Hall has applied a similarly rigorous but slightly different edit to the original and the equally excellent Concrete and Wood, with the result that Brick Mini comprises buildings and structures that will both appeal on an immediate wow level to a general audience yet, at the same time, cerebrally nourish an architecturally literate audience wanting a little more insight.

“People often consider these as simply picture books, but there are actually about 20,000 words in each one," says Hall. "The smaller format means you can drop them in a bag and read them on the move. The introductory essay by Dan Cruickshank alone is worth the price. He explains the origins of brick, including his experience of seeing adobe bricks made by hand in Yemen, and elucidates on the qualities of brick, citing some extraordinary examples throughout history. It’s a fascinating overview.”

“I’m excited that the mini format will introduce Brick to a different audience. I’ve always hoped to reach creative people who wouldn’t normally consider buying a book about architecture. These little books are cheaper and cuter. What’s not to like? They make great gifts, too.”

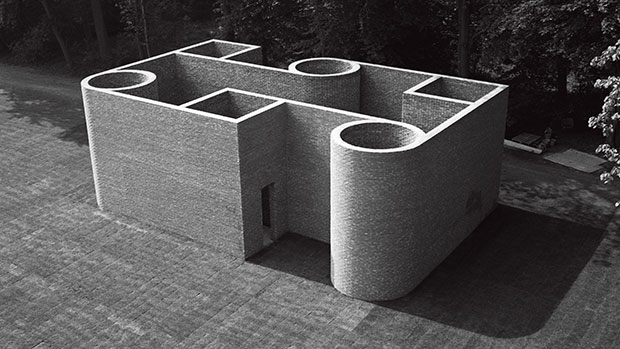

In it you'll find Bavarian viaducts comprising over 26 million bricks, ziggurats from Mesopotamia, the Great Wall of China, a Peter Celsing church, a Per Kirkeby sculpture park, warehouse stores by sculptor James Wines' that playfully challenge what a building could be alongside compelling descriptions of buildings you're more familiar with - Battersea Power Station in London, or the Gladstone Gallery in New York with its unusually long, dark grey bricks.

"I wanted to have a range of typologies, scale and building types in order to eke out the most interesting examples," says Hall. I wanted to encourage a change in the public perception of brick from something banal and ubiquitous, to something of wonder and potential. I hope that when people look at the images in the book they will see that."

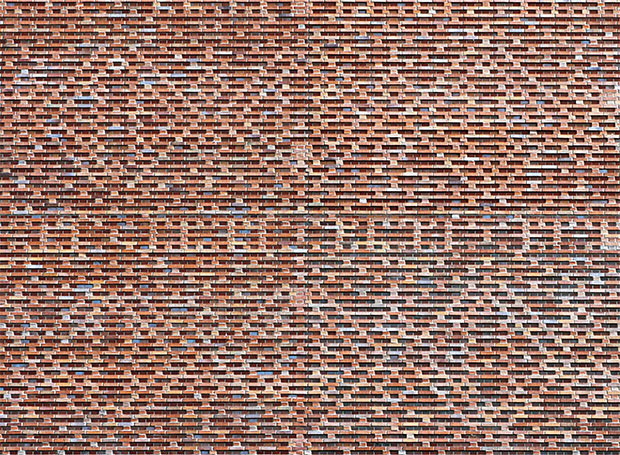

There's a rather touching section in the introduction to the book where Hall describes how, as a kid, he watched the bricks of his house turn salmon pink as the sun set one evening. Then, as it grew darker, he noticed darker lines on the surface of the bricks. These, his father explained, were where the bricks had been piled up during firing.

"Most people at some point have picked up a brick and looked at the texture," says Hall. "A brick is knowable, and you can look at a brick building and understand how it’s made. It’s bricks glued together with cement. Whereas if you look at a concrete or steel building it has an industrial scale to it that can be incomprehensible.

"And brick ages very nicely, in a way that other materials don’t. Brick buildings look more approachable and gentle and warm, as they get older. They show their age in a likeable way.”

We’d like to think our book Brick has improved over time and, in its funky new format, is easier to hold, read and take with you. See for yourself by buying a copy of Brick mini format in the store today.