Did you know that artist architecture is a thing?

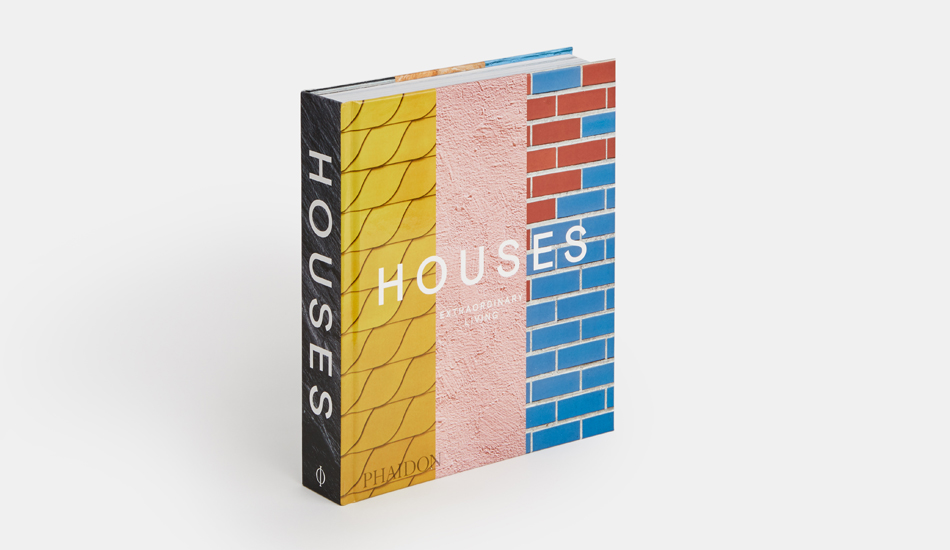

There are plenty of places made by artists in our book Houses (but you might not want to live in some of them...)

Theo van Doesburg, the Dutch 20th century Dadaist and De Stijl pioneer, was a pretty special artist any way you look at it. However, he was particularly remarkable for the way he managed to work as an architect, as well as an artist.

His Studio House, built in 1930, towards the end of his career, features in our new book Houses: Extraordinary Living, and is, as the accompanying text explains, “the culmination of van Doesburg’s attempts to translate the tenets of Neo-Plasticism - a Modernist preoccupation with shifting volumes and sliding planes - into a built form.” The entry goes on to explain that, while building shouldn’t be viewed as a purely a De Stijl creation, "traces of the kinetic spirit of van Doesburg’s early compositions can still be seen here.”

Of course, most artists have to collaborate with registered architectural practitioners in order to build their dream homes. Often these joint ventures are remarkably successful, such as when the British ceramicist Grayson Perry worked with the London practice, FAT, to create a whimsical holiday villa, A House for Essex (above).

“Overlooking the scenic Stour Estuary is this eccentric house, commissioned by philosopher and critic Alain de Botton’s Living Architecture program: it is artist Grayson Perry’s “chapel,” which enshrines and celebrates the history of Essex, his home county,” explains our new book. “The chapel’s architecture is inspired by Russian stave churches; the exterior is decorated with around two thousand tiles; and the golden roof is topped with sculptures, all designed by Perry.”

Sometimes, however, these joint ventures go awry. Take the Turbulence House, a 2005 home built by the American architect Steven Holl for the artist Richard Tuttle, out in the wilds of New Mexico.

“The arched structure consists of thirty-two prefabricated metal sections, the largest of which weighs a ton, bolted to flexible metal ribs; the home’s curving, segmental metal-panel skin appears to be stitched together like a quilt,” explains our book, before adding, “It is not comfortable. Tuttle has said: “It’s too hot in the summer, too cold in the winter.”

Nevertheless, the building does have its charms; it is, our book explains, “a form of desert visual poetry. The 'Turbulence' in the name references the wind that howls through its center, carving a curving void not dissimilar to an inverted desert canyon, within which is the entry door.”

The British artist duo Tim Noble and Sue Webster had better luck when they commissioned a house and studio from the-then up-and-coming architect David Adjaye. This warehouse conversion, dubbed the Dirty House, came with a clear brief. “The couple wanted a clear delineation between home and work,” explains our book, “the gutted building was therefore converted into two double-height studios downstairs, with their home above. The building is painted concrete and brick, which distinguishes it from the surrounding redbrick buildings and signals the private activity within.”

But perhaps the most successful artist-built houses are those that are created at one remove. The architect Frank Gehry still owns the Gehry residence, the remarkable, 1978 home he built around a fairly normal suburban house in the Santa Monica district of LA, which, with its wild angles, choices of materials and unconventional forms, drew on Gehry’s artsy milleu, as our new book explains: “In receiving the Pritzker Prize in 1989, Gehry reflected on the impact of his “artist friends” Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, Claes Oldenburg, and Ed Kienholz.

"In trying to find the essence of my own expression, I fantasized that I was an artist standing before a white canvas deciding what the first move should be. That was a moment of truth.”

For more on the wild side of domestic architecture order a copy of Houses: Extraordinary Living here.