These Brutalist buildings look like they shouldn't stay up

A smart choice of materials and techniques enables architects to dazzle as Atlas of Brutalist Architecture reveals

Brutalism not only breaks away from the Modern movement, which, as our new Atlas of Brutalist Architecture explains, was “increasingly judged to be effete and bourgeois,” towards end of the 20th century. It also defies the simple physical limitations that held back earlier generations of architects.

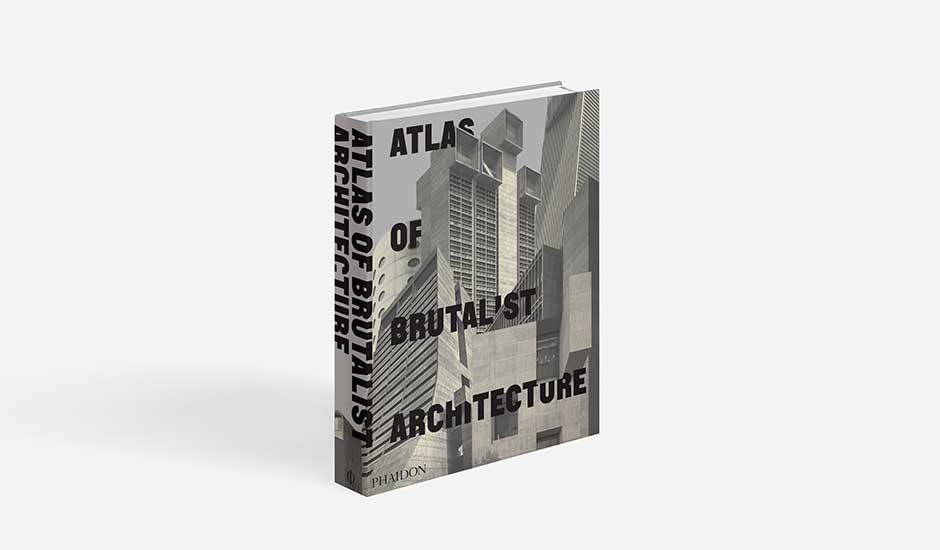

Housing blocks, water towers, office buildings, viewing platforms and all manner of other constructions could, in the post-war period, be built relatively cheaply from reinforced and pre-stressed concrete and high-grade steel, enabling architects to create structures such as this handful we plucked from the huge array of 850 plus brutalist masterpieces in our new Atlas.

Covering over 100 countries and featuring the work of nearly 800 architects, this ambitious atlas is the only place to find Brutalist architecture, both existing and demolished in over 100 countries by over 800 architects. We hope you enjoy our latest edit from this big, bold book.

Grand Central Water Tower, Midrand, South Africa, 1996 by GAPP Architects & Urban Designers (main pic) This spindly, conical water tower not only needs to hold gallons of precious hydration for this growing region, between Johannesburg and Pretoria. The cone’s upper section was also designed to house a restaurant. Fortunately, its materials are up to the task. It is “constructed from pre-stressed concrete in horizontal segments shaped by bespoke cone-shaped formwork,” explains our book. “Its upper reaches are post-tensioned by thirty-two horizontal rings and four buttresses – a sufficient support for containing the 6.5 million litres of pressurized water in the top half of the structure.”

De Rotterdam, Rotterdam, the Netherlands, 2013, by OMA The upper portions of these mixed commercial and residential blocks in the Netherland’s second-largest city might look like they’re about to topple over. However, Rem Koolhaas’s practice, OMA, created these jagged outlines to meet the needs of the building, and to give De Rotterdam a neighbourhood-like feel. “Their offset orthogonal volumes are configured according to the demands for the apartments, offices and hotel that they accommodate,” explains our Atlas. “Depending on the viewer’s stance, the uneven cantilevers and irregular floor plates create a changing profile. Through this range of programmes, the architects aimed to ‘reinstate the urban activity once familiar to the neighbourhood’.”

The Timmelsjoch Experience Pass Museum, Timmelsjoch, Austria, 2010, by Werner Tscholl (above) High in the Austrian Alps, this museum was founded to commemorate the construction of the Timmelsjoch Pass, a mountain road that was “slowly, arduously constructed by pioneering workers who transformed a former mule track into a safe and stable thoroughfare.” While this Cor-Ten steel building might have been a bit easier to build, it is no less impressive. “The museum, designed by local architect Werner Tscholl, was conceived in harmony with the natural rocky landscape, and its precarious chamfered form emulates their profiles,” says the Atlas.

Armstrong Rubber Company Building, New Haven, Connecticut, USA, 1968, by Marcel Breuer Breuer could easily have packed a couple more floors into the upper tower in this tyre company complex. However, he chose to break up the space between the firm’s offices and its storage and labwith a pleasing space bridged by supports. "While the lower two-storey research facility and warehouse are fully integrated into the ground in an unobtrusive manner,” explains our book, “the office block above is elevated in the air, supported by rectangular pillars and three staircase towers positioned at the edges and in the middle of the structure.”

‘On the Cherry Blossom’ House, Tokyo, Japan, 2008, by AXL Tokyo’s high population density and strict planning rules, such as its Sunshine Laws that restrict the amount of daylight a building can obscure, has pushed architects such as AXL’s Junichi Sampei to create vertiginous homes in tricky urban spaces. “The compact house has three levels and a basement,” explains our book. Each floor branches out, tree-like, from a central spiral staircase, leading, ultimately up to the second-floor living area, from where the house's inhabitants can admire the annual cherry blossom.

São Paulo Museum of Art, São Paulo, Brazil, 1968, by Lina Bo Bardi The stilts that support this glass and concrete block enable the museum to enjoy better daylight and lines of sight over the city’s neighbouring parkland. “The main galleries are lifted on four massive concrete columns to provide uninterrupted views over the Parque Trianon,” explains our book, “while above street level, a structurally impressive 74 m (243 ft) span bridges a huge space for public gatherings.”

Praxis Home, Mexico City, Mexico, 1970, by Agustín Hernández Navarro The Mexican architect and sculptor Agustín Hernández Navarro built this, his home and studio, in the capital’s hilly Bosques de las Lomas neighbourhood, taking advantage of modern materials to pay tribute to older, indigineous styles. “Expressing the architect’s fascination with pre-Hispanic motifs, which are a consistent theme in his work,” says our Atlas, “the concrete house recalls two interlocking pyramids that seem to defy gravity and the usual predominance of vertical walls.”

Keen to see more? Then get our new Atlas of Brutalist Architecture. Presented in oversized format with a specially bound case with three-dimensional finishes, Atlas of Brutalist Architecture conveys the power and strength of over 850 Brutalist buildings - including new, old, demolished and threatened - in over 100 countries featuring the work of nearly 800 architects. the world's finest examples of Brutalist architecture brought to life through 1000 beautiful duotone photographs in one BIG, bold and truly beautiful book. For more beautiful examples of Brutalism of every kind get our new Atlas of Brutalist Architecture here.