A Brutalist guide to Open House London

Londoners – here’s how to satisfy your craving for mid-century concrete this coming weekend

This coming weekend some of the British capital’s best-known buildings unlock their doors and put out the welcome mats, as part of Open House London. London’s most ornate buildings and venerable addresses are taking part in the programme, including 10 Downing Street, the Royal Courts of Justice and Burlington House. However, it isn’t all Gothic spires and Palladian columns; there are plenty of Brutalist inclusions in this year’s selection. Here’s a few of the best, courtesy of our Atlas of Brutalist Architecture.

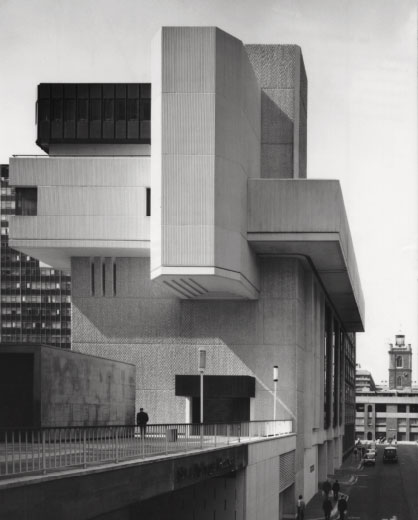

The Royal College of Physicians, Denys Lasdun & Partners, 1964 (above) London is often said to be a city where wildy differing architectural styles abut on another. However, Lasdun’s building, though very much a product of its time, was designed to fit into this site, on the edge of Regent’s Park, once occupied by the fine, early nineteenth-century Someries House, which had been damaged during World War II. “A condition of its demolition was that the replacement should complement the nearby Neo-Classical terraces and villas," explains our Atlas. "Denys Lasdun, one of Britain’s most important late-Modern architects, was selected to design it, and after weeks observing the college’s everyday activities, he came up with a solution for a complex social, ceremonial and academic space.” It's also a convenient and beautiful marker for the many cyclists who power round Regents Park's outer circle early on a Sunday morning.

The National Theatre, Denys Lasdun & Partners, 1976 This might be one of Britain’s foremost threatrical buildings, yet the architecture is a truly international concoction. “The theatre’s monumental concrete bulk recalls Swiss-French architect Le Corbusier’s work,” explains the Atlas, “while the various levels’ hovering planes are reminiscent of Fallingwater by American architect Frank Lloyd Wright. The theatre’s geometry also drew on historical precedents such as the ancient Greek amphitheatre at Epidaurus and the Gothic octagonal tower of Ely Cathedral.”

The Barbican Estate, Chamberlin, Powell & Bon, 1976 Brutalism isn’t always used for cheap, social housing. The Barbican was built on a bombsite within the City of London (home to the UK’s financial services), offering modern well-appointed homes made from the finest of materials. “A car park lies underground and the entire complex is pedestrianized,” says our Atlas. “The exterior facades are constructed of concrete bush-hammered on site. The crushed-granite aggregate’s monolithic appearance contrasts with the planted areas.”

Salters’ Hall, Basil Spence, John S Bonnington Partnership, 1976 The Worshipful Company of Salters may have been founded in the fourteenth century, yet its distinctly modern headquarters suits the organization, which today promotes the advancement of chemistry. “Basil Spence’s project is organized according to a rectangular plan, dominated by a double-height main hall at its heart,” explains the Atlas. “Its facades of textural in-situ concrete are also rectilinear, with projecting upper floors cut through by smoky glass in aluminium framing. Although the project as built differs from Spence’s original concept, it remains executed in dramatic masses of concrete with ribbed, bush-hammered and fluted finishes.”

Trellick Tower Ernö Goldfinger, 1972 Ever wondered what that bulge was at the top of this, West London’s most distinctive tower block? Our Atlas tells all: “Incised with narrow slit windows, the project is crowned by a projecting boiler house on the thirty-second and thirty-third floors, which is reflected in the fully glazed panels. In addition to the housing, the project included six shops, an office and centre for youth and women.”

Find out more about Open House London here; For more on the world’s most brutal buildings, order a copy of our Atlas of Brutalist Architecture here.