These Brutalist buildings are actually really beautiful

It might not be known for its pretty ornamentation or well-balanced forms but Brutalism can still embody beauty

Brutalism isn’t exactly a byword for beauty. Just as modernism arose out of a rejection of a certain type of ornamentation and prettiness, Brutalism rejected “the lightness and flatness of the Modern movement and the International Style a banal kit-of-parts solution,” our new Atlas of Brutalist Architecture explains. Nevertheless, there are plenty of Brutalist buildings that can look incredibly beautiful, as these highlights from the new Atlas of Brutalist Architecture makes clear.

Cathedral of Brasília, Brazil, 1970, by Oscar Niemeyer (above) Niemeyer, Brazil’s foremost 20th century architect, oversaw the creation of the country’s capital, alongside fellow architect and urban planner, Lúcio Costa. His cathedral, dedicated to Brazil’s patron saint, Our Lady of Aparecida, serves as the spiritual centre of Brasília.

“A whitepainted concrete dome marks an underground baptistery, and a concrete belfry projects from the podium,” explains our new book. “Held in place by a 70m (230-ft) diameter concrete compression ring, sixteen concrete ribs converge then shoot outwards to hold a concrete ceiling disc topped with a white cross.” Brutalism truly at its best anyone would agree.

Stykkishólmur Church, Stykkishólmur, Iceland, 1990, by Jón Haraldsson This Catholic church on the western coast of Iceland may be fashioned from concrete, yet its shape draws on more traditional, organic forms. “The church’s most striking feature is the bell tower made from two concrete fins, apparently inspired by the form of a gigantic whalebone,” explains the Atlas. “They also echo the slopes of the nearby mountains and open out to welcome visitors through the entrance at the tower’s base. A counterpoint to this is the curving, semi-cylindrical rear tower, part of which is glazed, allowing daylight to fall into the chancel.”

Salk Institute, California, USA, 1965, by Louis I Kahn Though this Californian building is dedicated to the sciences, rather than the arts, it is still a sublime work by an architect who drew on the past to create this futuristic building. “Located on a bluff overlooking the Pacific Ocean, this laboratory complex was created to accommodate the biological research activities of the Salk Institute,” explains our Atlas. “In its massing, use of materials and relationship to the environment, the laboratory complex manifests the transformative influence of the medieval and Roman architecture that Estonian-born architect Louis Kahn encountered during a tour of Europe in 1928. Comprised of two symmetrical structures flanking a central, open-ended courtyard, the project is organized over six floors, with levels alternately accommodating services and laboratory space.”

Bergisel Ski Jump, Innsbruck, Austria, 2002, by Zaha Hadid Architects The British-Iraqi architect Zaha Hadid won the competition to replace Bergisel’s old ski jump, in 1999, and set about creating a challenging new structure, which also housed a café and a viewing platform, by combining two, familiar forms. “Inaugurated to celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of the Four Hills Tournament in 2002. Hadid called the ski jump ‘an organic hybrid’ between a bridge and a tower,” explains our new book. “Intended not just as a functional facility but planned as a landmark, it is one of Innsbruck’s most visited attractions.”

Bruder Klaus Chapel, Mechernich, Germany, 2007, by Peter Zumthor Brutalism, needn’t been big and machine built, as Zumthor proves in this simple, rural chapel. “Its rough, layered concrete shell with prominent lumps of aggregate pares back at a triangular doorway – the narrow entry gives way to a surprising interior,” explains our new book. “Constructed back-to-front, the blackened conical shape of the interior relays the order of construction: a timber tipi-like structure was first assembled, framed by slim tree trunks that encased the formwork. Later, once the concrete had set, a controlled fire was lit at its heart, slowly devouring the wooden poles and leaving only a black residue and the ribbed inner texture.”

Villa Kogelhof, Kamperland, the Netherlands, 2013, Paul de Ruiter Architects Paul de Ruiter Architects were asked to create this house, which forms part of an eco estate in the Netherlands, from which residents can take in the beauty of the natural world. “The practice designed a luminous, transparent interior free from domestic details that would detract from the setting,” explains the Atlas. “Elements such as wardrobes, garaging and storage, which do not require daylight, are hidden in the submerged wing, leaving the upper residential level a pristine place for contemplation.”

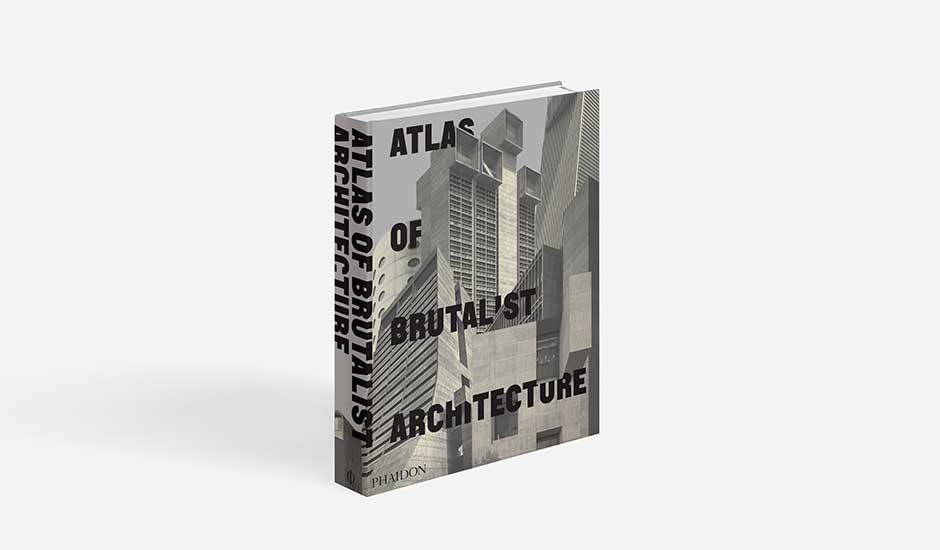

Presented in oversized format with a specially bound case with three-dimensional finishes, Atlas of Brutalist Architecture conveys the power and strength of over 850 Brutalist buildings - including new, old, demolished and threatened - in over 100 countries featuring the work of nearly 800 architects. the world's finest examples of Brutalist architecture brought to life through 1000 beautiful duotone photographs in one BIG, bold and truly beautiful book. For more beautiful examples of Brutalism get our new Atlas of Brutalist Architecture here. And look out for our next story on the Atlas tomorrow.