How Ernö Goldfinger brutalised both east and west

The architect built iconic towers on both sides of London - and was immortalised as a Bond baddie

Architecturally minded visitors might lose their bearings when riding on London’s public transport system. Take the Docklands Light Railway out east, past Poplar, and you see a striking twenty-six storey concrete apartment block with a distinctive service tower.

Ride the Hammersmith and City Line out by Westbourne Park and you see another, very similar, thirty-one storey tower, looming over the city.

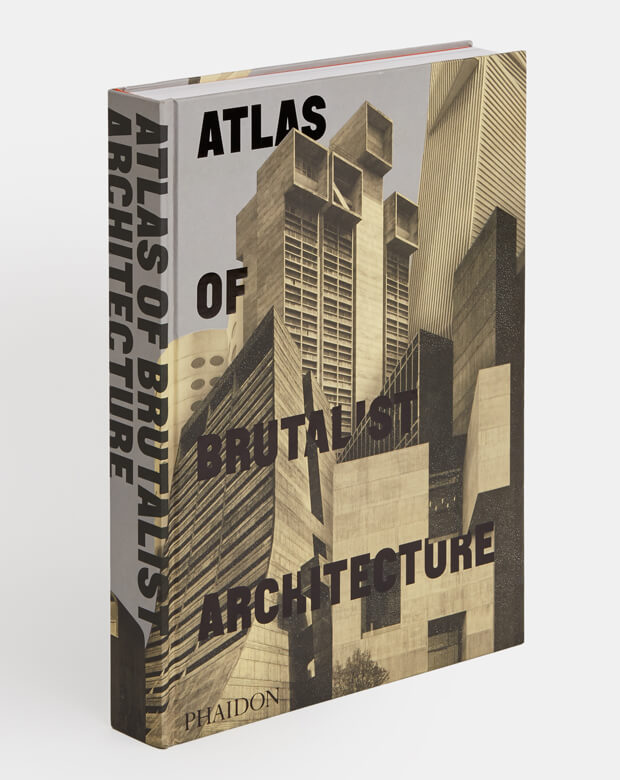

Both are the work of a Hungarian émigré, Le Corbusier acolyte and committed modernist Ernö Goldfinger, born on this day September 11 in 1902, as our new Atlas of Brutalist Architecture explains. Balfron Tower, in Poplar East London, is the earlier building, constructed in 1967 by the London County Council (LCC) to accommodate rapid growth in London’s post-war housing

“In keeping with Goldfinger’s progressive view of architecture for social good, the design was imagined as a way to rehouse a community street by street. The tower accommodates 136 flats and ten maisonettes that interlock in section, arranged three per bay with enclosed access galleries to the service tower on every third floor,” explains our new book. “The tower also houses a launderette and communal recreation rooms, and its separation from the flats gives the project its unusual profile.

“Constructed of reinforced concrete, with carefully detailed bush-hammered finishes, the balconies to every flat are clad in timber. Of his design, Goldfinger noted, ‘Everything I did, I did as if it was done for me.’ Perhaps unsurprisingly, he and his wife lived in the tower for two months, gaining feedback from residents about what they did and didn’t like.”

Some of Goldfinger’s findings were included in the architect’s 1972 residential development for West London, Trellick Tower. “A location that features in dozens of films and music videos, its arresting profile is shaped by a separate thirty-five-storey lift and service tower that links to the main block at every third floor.”

And that tower wasn’t the only feature Goldfinger took from the East of the city when building in the West.

“Like the preceding projects, at Trellick Goldfinger maintained the idea of balconies for every flat, large strip windows to maximize daylight for occupants and a structure of bush-hammered in-situ reinforced concrete with timber-clad balconies,” explains our new book. “In addition to the housing, the project included six shops, an office and centre for youth and women.”

All these social responsible additions didn’t endear Goldfinger to every Londoner. He was known for his temper and, in 1959, Ian Fleming – hearing of this character flaw through a relative of the architect’s wife, and possibly taking offence at his architectural style and politics (Ernö was avowedly left wing) – chose ‘Goldfinger’ as the title and antagonist’s surname in his new James Bond novel.

The architect attempted to sue, but eventually settled out-of-court. Fleming may have him as a baddie in print and on the screen, but Goldfinger’s more edifying legacy lives on in London’s built environment (and our brutal books).

For more on the world's beautiful, brutal buildings, get our new Atlas of Brutalist Architecture.