The Medieval wonder that could welcome Trump

What’s so special about Britain's Westminster Hall? Our book, Wood, gets behind the politics

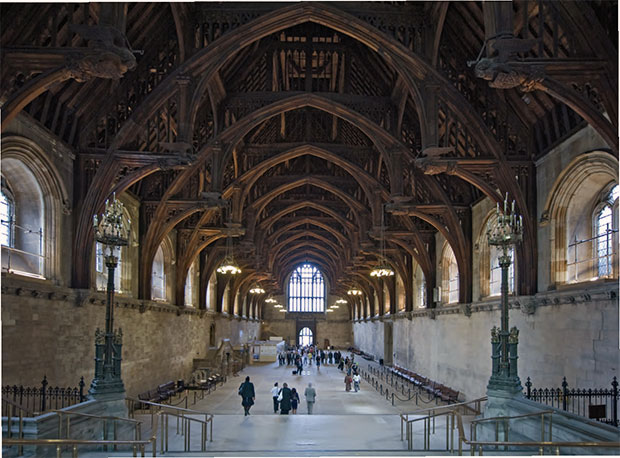

It’s big, old and wooden, occupies a unique place in world politics, and some people wonder how it got there in the first place. When President Trump comes to Britain he could have the honour of addressing the UK’s members of parliament beneath the hallowed beams of Westminster Hall, within the Houses of Parliament.

Many within British politics would prefer if the new US head of state not to put in an appearance here, yet fewer understand the cultural and architectural significance of this eleventh century.

“Westminster Hall dates from 1097,” writes William Hall in his new book, Wood. “Originally its roof was likely supported by three columns, but these were replaced in the reign of Richard II by the royal carpenter Hugh Herland, creating the largest clearspan [unsupported] medieval roof in England, some 73 x 20 m (240 x 66 ft.). The room has witnessed some extraordinary events: the trials of Guy Fawkes and William Wallace took place here; it survived a massive fire that destroyed much of the old Palace of Westminster in 1834; a Provisional IRA bomb exploded here in 1974; and Nelson Mandela was afforded the rare compliment of being invited to address both Houses here in 1996.”

Yet, perhaps the most interesting thing about the hall is not its famous visitors, but the incredible ingenuity that went into its construction.

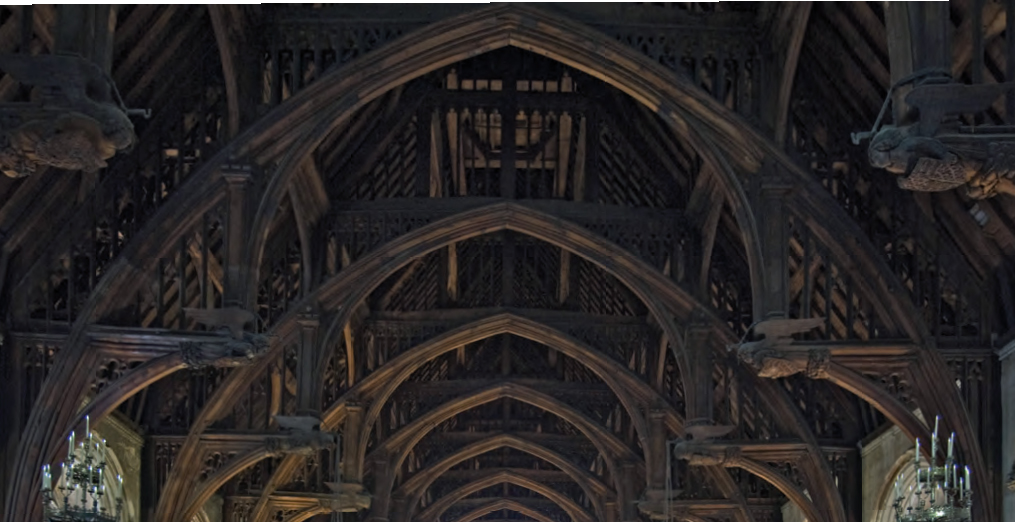

“The most spectacular wooden structure from the European Middle Ages is the timber-framed roof of Westminster Hall in London, constructed between 1393 and 1397 (67). It spans an aisle of 21 m (68 ft.) without supporting posts,” explains the writer and broadcaster Richard Mabey in Wood’s introduction. “Though there are medieval roofs in Sicily with greater spans, they achieve this by the use of single giant conifers of a kind unavailable in England, and Westminster’s structure remains the most audacious and intelligent.

“The designer and master carpenter was Hugh Herland. He personally selected the oak trees in Surrey, probably in Alice Holt Forest, and then had them cut and jointed in a framing yard in Farnham. 690 tonnes (760 tons) of wood lay on the ground, each brace and mortise marked with Roman numerals, imagined and intuited by Herland into a gravity-defying canopy. The wood was then taken by cart and boat to London and assembled into what is basically a series of mutually supporting triangles of hammer beams, hammer posts and sweeping arches. How it works is still something of an enigma. It is one of those wooden marvels where the carpenters, having dismembered large numbers of trees, then reassembled them in what is essentially another super-tree, a formal arrangement of trunk and fractal branching. The writer William Bryant Logan has beautifully described how the structure allows gravity to flow along rafters, down walls and into the ground – the roof, Logan writes, ‘is a force made visible’.”

It remains to be seen whether those architectural forces will come into close contact with one of the newer sources of power within global politics. For more on this wood within architecture past and present order a copy of Wood here. And if you're looking for examples of how artists both celebrated and unknown have resisted the powers that be in recent times, check out Liz McQuiston's scholarly but thoroughly readable and copiously illustrated Visual Impact Creative Dissent in the 21st Century.