A Carlo Scarpa guide to Venice

Heading to La Serenissima for the art? Great! But don't forget to take a look at the city's architecture too

Just like the Venice Biennale, the Venetian architect Carlo Scarpa demonstrated how a city can be both antique and thoroughly up-to-date. The 20th century Italian architect was, writes Robert McCarter our book’s introduction, “deeply embedded in the archaic and anachronistic culture of Venice, while also transforming the ancient city by weaving the most modern of spatial conceptions into its material fabric. To a degree unmatched by any other Modern architect,”McCarter explains, “Scarpa stood in two worlds: the ancient and the modern. Here are a few of his best-known Venetian works to look out for if you're heading to la Biennale.

The Venice Biennale Ticket Office Scarpa was invited to create a number of works for the 26th Venice Biennale, back in 1951, including this ticket booth, which is still standing at the entrance to the Giardini di Castello, though it no longer dispenses tickets.

“The straight, curved, thicker and thinner sections of the wall are staggered along the Giardini’s edge, standing in no apparent geometric relation, as if they were fragments of some ancient ruin.” writes McCarter. “With large planters at both ends and near the middle, this wall anchors the free-standing entrance and ticket office to its site, physically and spatially, so that it is read less as an object, and more as part of a larger landscape pattern. A low, cylindrical wall houses the ticket office in one third of its volume; the remaining section is divided into triangular floor sections, with hexagonal walls behind. The ticket office’s concrete floor is raised and a full-height wall of black, steel-framed wire glass is set along the two straight lines radiating from the circle’s centre. The entrance door pivots on a post set at the circle’s centre point, making its own matching inner arc when it opens.”

The Italian Courtyard Pavilion “In 1950–2, Scarpa was also commissioned to make changes to the main, and largest, Biennale building, the Italian pavilion,” McCarter explains. “Creating a new rectangular courtyard within the existing building, Scarpa removed some of the previously built smaller rooms to make a new transition space where visitors could relax in the garden-court between exhibits. He stripped off the brick walls’ plaster, providing a consistent outer wall for his freestanding canopy structure, which provides sheltering cover for those passing between the two doorways. This hovering, 46 centimetre (18 in) thick concrete slab does not touch the outer walls, allowing sunlight to wash them. The canopy is carved into by three arcs of differing diameter, a small semi circle at the centre, with two quarter-circles at either end. Each pillar stands only halfway under the edge of the canopy; the actual load bearing is carried through a small steel sphere that rests on a pyramidal stand set atop each pillar, inset from the edge. The plants growing from the top of the pillars obscure these supports, so that the massive roof canopy appears to hover just above the load-bearing pillars.”

The Venezuelan Pavilion Scarpa did not limit himself nationally when contributing to the Biennale, as this beautiful work for Venezuela’s delegation makes clear. “The Venezuelan Pavilion was part of the Biennale’s expansion in the Castello Gardens,” McCarter explains, “initiated in 1951, this intended to provide pavilions for several countries lacking dedicated exhibition spaces. In 1953, Scarpa’s former student, Graziano Gasparini, an Italian painter and architect living in Venezuela, recommended he be commissioned to design the new Pavilion. The site, which had three existing trees, is located between the Russian and Swiss pavilions on the garden’s southwestern-most avenue, adjacent to the lagoon. Rather than beginning with an existing building, as he had done with most of his earlier built works, this was one of the relatively few freestanding new buildings realized to Scarpa’s designs."

The Olivetti Showroom A typewriter showroom might not seem like a prominent commission these days, yet sixty years ago Scarpa’s work for Olivetti was viewed in quite a different light. “In the 1950s and 1960s, the Olivetti Company was one of the world’s leading industrial design firms, perhaps best known for the high-quality design of their typewriters,” McCarter writes. The company’s founder, Adriano Olivetti, created the Olivetti Prize in the early 1950s to recognize design excellence in architecture. In 1956, at the urging of Bruno Zevi, Scarpa received this prize, and the next year Olivetti hired him to design their new showroom on Piazza San Marco, Venice’s most important public space.

“The corner site’s narrow front opened on to the ground floor portico of the Procuratie Vecchie on the piazza’s northern side across from the Correr Museum’s windows; its longer side ran along the Sottoportico del Cavalletto, a passageway running under the building’s first floor leading to a bridge over the Rio del Cavalletto canal. This site is perhaps the most severely circumscribed context in which Scarpa ever worked, embedded in both the most important fabric of the historical city and a popular tourist site. Yet, like Michelangelo, who apparently was unable to conceive a statue’s form before seeing the stone block from which it was to be carved, Scarpa believed that the freedom to make form and space only came from the imposition of strict limitations. Nearly all Scarpa’s designs were made for complex, densely layered historical contexts, yet, rather than making the design more difficult, he paradoxically believed the opposite to be true, ‘When the context is fixed, perhaps it makes the work easier.’”

Scarpa created a remarkably accommodating building that suited the city, right down to its watery foundations. “The showroom’s celebrated floor was made using Scarpa’s own unique variation on traditional Venetian terrazzo: a light greywhite cement bed into which rectangular mosaic tesserae of Murano glass paste, of four different colours and sizes, were hand-placed in a pattern of horizontal rows. The depth of the lustrous, highly reflective surfaces of the mosaic glass tesserae, as George Ranalli notes, ‘make the floor appear to ripple and undulate like moving water.’”

The Correr Museum “In 1952, Scarpa was commissioned to renovate and reorder the collection of the Correr Museum, the main museum of Venetian art and history,” McCarter writes. “Since the 1920s, the Correr has been housed in the Procuratie Nuove buildings along the south side of Piazza S. Marco. Scarpa worked from 1952–3 on the first floor historical collection and renovated the second floor painting galleries from 1957–60. On the first floor, Scarpa left the period carved-wood ceilings and Venetian terrazzo floors in place, plastering and painting the walls an off-white to form a quiet background for the paintings, etchings, maps, banners and other historical artefacts.”

However, the architect did not limit himself to the building’s structure, but also built the cases, frames and display devices for all the museum’s works and artefacts.

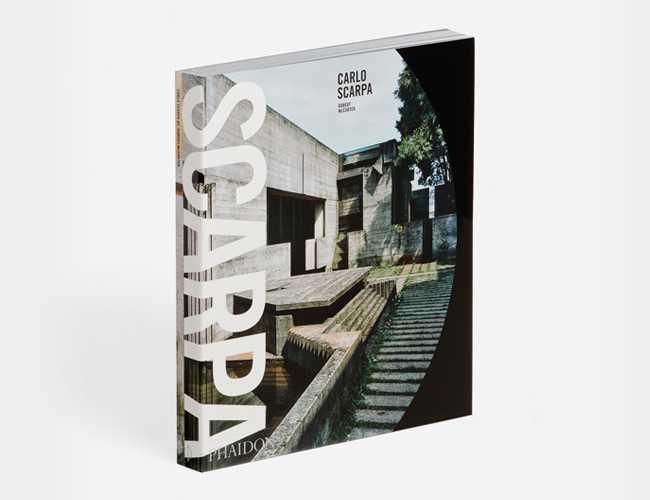

For more on this influential architect’s work order our Scarpa book here. For more on the influence of events such as the Venice Biennale get Biennials and Beyond.