A Brutalist guide to the film High-Rise

The architecture that informed the new movie adaptation, courtesy of This Brutal World's Peter Chadwick

The British novelist JG Ballard did not write about any specific building in his dystonian 1973 novel, High-Rise. It was partly inspired by the residential bickering Ballard's parents' experienced while in a block of executive apartments in Red Lion Square, London, during the mid 1960s, and also based as the unrest the author came across among his fellow vacationers while staying at a holiday complex on Spain's Costa Brava.

However, when British director Ben Wheatley came to adapt the novel for the screen, he and his colleagues found a wealth of Brutalist architecture to inform the look and feel of his 20th century period piece.

Wheatley's appreciation for Brutalism, a once unloved style of architecture now very much in resurgence, is shared by the designer and author Peter Chadwick, whose book, This Brutal World, is due out later this spring. Here Chadwick guides us through the facades that inspired the film.

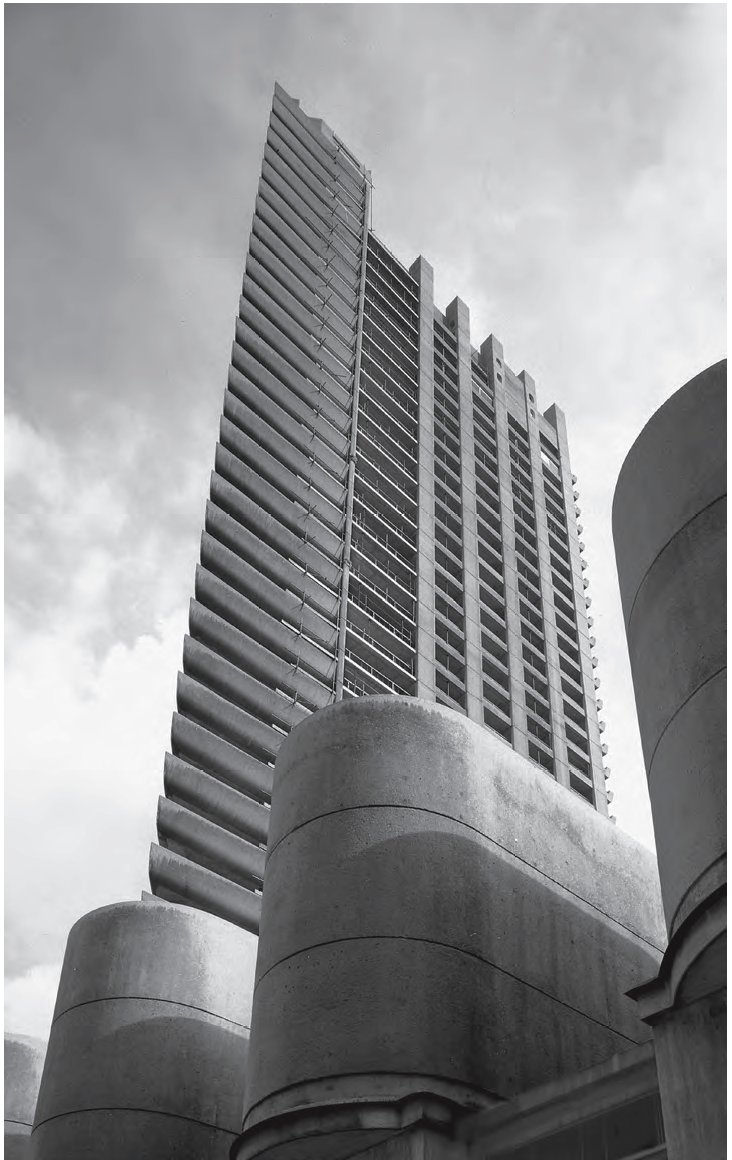

The Barbican London's grade II listed estate was being completed as Ballard wrote his novel, and the development has been cited as a reference for the new High-Rise adaptation by Wheatley. Apartments in this complex, created by the British practice Chamberlin, Powell and Bon, were marketed towards the professional classes, with its architects adding in the high walls and concealed entrances, in the hope that these would ward off unwanted outsiders.

This did not put off our author, who has made regular visits to the development over the past four decades. “I always manage to seek out yet another new viewpoint,” says Chadwick. “When it was officially opened in 1982, Queen Elizabeth declared it to be ‘one of the modern wonders of the world’, and I am more than inclined to agree.”

Balfron Tower, Trellick Tower Just like High-Rise's domineering architect, Anthony Royal, in High-Rise Hungarian-born Erno Goldfinger moved into a top-floor apartment 130 on the 25th floor of the building he designed, Balfron Tower, in the East End of London for a few months in 1968. Goldfinger, like Royal, held drinks receptions for the residents on the lower floors, and drew on their suggestions when designing another, similar looking skyscraper, Trellick Tower, on the western side of London, which he completed in 1972.

He wasn't (quite) as despotic as his High-Rise counterpart, and Chadwick has some sympathy for heroic figures like Goldfinger. “Lasdun, Lubetkin and Goldfinger - they all had heroic-sounding names that rolled off your tongue. And the band Saint Etienne eloquently captured the spirit of these architects in the lyrics of their track ‘When I was Seventeen’: ‘Lubetkin, Corbusier, van Der Rohe, Mendelssohn. Modern, modern, Brutalist architecture. Future, future, the future is clean and modern.’"

Unité d’Habitation Le Corbusier's paradigm of city-living development, built between 1947 and 1952 in the French port of Marseilles, also inspired the look of the new movie. Like many other Brutalist developments, the Unité d’Habitation's all-encompassing approach to city living, with its own communal rooftop garden, running track and paddling pool, seems a bit antiquated today.

However, this hasn't prevented 21st century enthusiasts from finding new uses for Le Corb's creation. New York's Museum of Modern Art acquired a complete fitted kitchen from the development in 2012, and a successful contemporary art gallery opened on the block's roof terrace in 2013. For Chadwick, the Unité's recent success is proof that, while plenty of Brutalist building was built on low budgets, the style can also attain greatness. “In the work of architects such as Marcel Breuer, Le Corbusier, Louis Kahn and Paul Rudolph, Brutalism found its highest expression,” Chadwick argues.

Bangor Leisure Centre This functional, anonymous 1973 creation was marked for demolition to make way for a newer, larger leisure centre. Wheatley's crew reached the sports facility just in time, finding a wealth of period-perfect settings, within the condemned building. How can the look of a building be simultaneously celebrated cinematically and condemned bureaucratically? It's a contradiction that lies at the heart of Brutalism.

“Whereas once so much of the world’s Brutalist architectural heritage was neglected, unloved and in danger of being torn down and relegated to land fill, now,” writes Chadwick in his new title's introduction, “here in this book, we can celebrate the power and beauty of this most compelling style of architecture.Brutalism can now shed its sense of danger and has come full circle, from utopia, to dystopia and back again.”

For more Brutalist insight and many more great images, order a copy of This Brutal World here.