Frank Lloyd Wright's Fallingwater explained

Discover how this perfect mid-century holiday home, kick-started the brilliant US architect's flagging career

In 1935 some thought Frank Lloyd Wright was finished. The great American architect had last completed a building in 1929, a commission from his cousin. He had already written his autobiography. The Great Depression had dampened down the demand for new constructions, leading many to conclude that this pioneer America modernism, had, as the US architecture historian Joseph Connors puts it “pointed the way to the promised land that he would never himself enter.”

However, Wright was not completely finished. In 1932 Wright established Taliesin Fellowship, a kind of apprenticeship-cum-works programme run out of his remote Wisconsin studio. In 1934, the 24-year-old art student Edgar Kaufmann Jr., enrolled.

Kaufmann was the son of a Pittsburg department store magnate and, following his son’s involvement with Wright’s practice, Kaufmann Sr. approached the architect to design a new family summer home on Kaufmann’s country estate in the Appalachian mountains of western Pennsylvania.

The land had formed part of the department store’s portfolio, and was being used by both the Kauffmanns and the department store employees as a holiday camp. However, the family assumed personal ownership in 1933, and decided to update the plot’s dilapidated buildings.

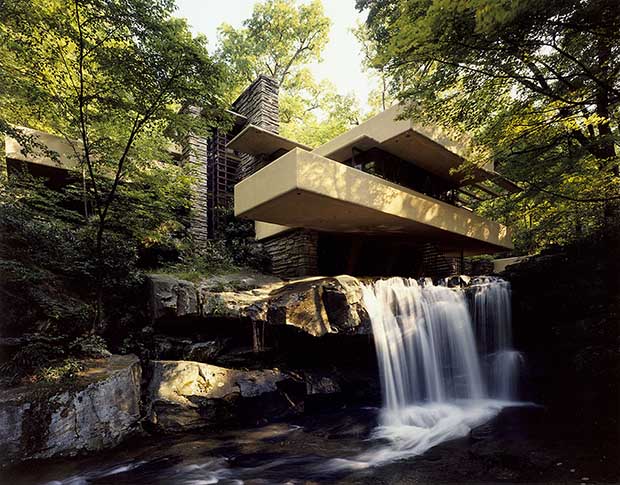

In particular the Kaufmanns liked the waterfall that coursed through the spot; this white-water stream, Bear Run, is a five-mile tributary of Youghiogheny River, and was a feature the family hoped to accentuate in their new home.

Wright accepted the commission, visited the site in December 1934, and gestated on the project. However, did not produce single drawing over the next nine months until his studio received a call from Mr Kaufmann, announcing a surprise visit. In the two hours it took his client to drive to Wright’s studio, the veteran architect drafted out fairly clear plans for the house, directly on to the site survey, using different coloured pencils to indicate different floors. The diagrams were a bit scrappy, in Kaufmann’s opinion, but he approved the plans.

This is all the more remarkable because the department store magnate had imagined his house would look on to the falls, rather than sit above them. However, Kaufmann was won over by Wright’s argument that the house would allow the waterfall to become an integral part of their lives, and could constantly hear the falling water while inside the dwelling.

What’s equally impressive is how close this swift draft matched the final building. The initial drawings were more or less realised at Bear Run, leading the architecture critic and Wright scholar to remark on how Fallingwater had been “conceived with an awesome finality.”

As a building, Fallingwater looks very different from Wright’s earlier work. There’s none of the stained glass and beautiful woodwork of his earlier homes. This three storey, steel, glass, sandstone and reinforced concrete dwelling has such stark, clean lines, that many regarded as Wright’s answer to Mies van der Rohe and co.’s burgeoning International Style.

Wright denied this, pointing to the way in which this, square-ish house, formed from interlocking planes, was not so very dissimilar from the Prairie style he had pioneered during the first few decades of the 20th century. The 2445 sq. ft. of overhanging terraces fit into the landscape as well as Wright’s earlier houses had, while the 2885 sq. ft. interior, with beautiful corner windows, open spaces, and stone floor, waxed to resemble polished river stones, provides both refuge from, and interaction with, the natural world.

Indeed, the most remarkable aspect of the house is the way so artificial a construction appears to fit so closely into the natural environment. Seen from the river it is as if the house has, in author Robert McCarter’s words, “grown out of the ground and sits in the light.”

“The natural setting is so integrated into the house that in occupying it we are constantly reminded of where we are by the sound of the waterfall,” McCarter writes. “the flow of space and movement inside and outside the floors and terraces, gives the house a sense of refuge while the views and sunlight are framed by steel windows, which act as spatial nets or webs similar to weaving stained glass in Wright’s earlier houses.”

Far from marking the end of Wright's career, Fallingwater began a new phase in his professional life; Wright lived to the age of 92 and completed hundreds of further buildings, including the Guggenheim museum in New York.

Yet, while the building marks a change in the architect’s practice – most notably in his pioneering use of concrete, which, at the time, was seen as dangerously modern by the consultant engineers – the house deserves its place within architectural history, not just because of its historical importance, but because of its undoubted perfection.

The house, which is open for visitors, was named in 1991 by the American Institute of Architects as the all time best work of American architecture. Proof that, for all the CAD renderings and drawing-table time a building gets, you really can’t beat the creative powers of a single genius, when it comes to producing a truly singular building.

For more on Fallingwater buy a copy of this study by Robert McCarter and for more on Frank Lloyd Wright more generally, browse through our beautiful Frank Lloyd Wright books here.