French Pavilion pairs Jacques Tati with Jean Prouvé

The French submission for the 2014 Venice Architecture Biennale interrogates and gently lampoons modernism

France was both the home of modernism, and the place where older, 19th century city centres have been preserved, with new, social housing often restricted to the suburbs. So how should we judge its building record, when considering the Venice Architecture Biennale’s director, Rem Koolhaas’s brief: Absorbing Modernity: 1914-2014?

Well, it’s certainly entertaining. The French Pavilion, as overseen by architect and architectural historian Jean-Louis Cohen, author of Phaidon's The Future of Architecture Since 1889, is certainly a hit in this opening week. Under the heading 'Modernity: a promise or a menace?', Cohen has split the show into four rooms, each offering a different view of 20th century architecture.

The first focuses on the French film auteur Jacques Tati’s 1958 comedy, Mon Oncle, and, more specifically, Villa Arpel, the parody of a modernist home that is the butt of many Tati jokes about idealised living, automation and consumerism. Using drawings and models of the villa, it’s a light and familiar way to look back on the clear order Francophone architects such as Jean Prouvé and Le Corbusier introduced to the world.

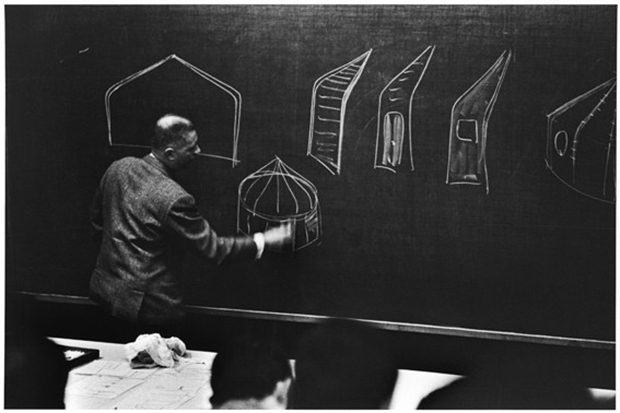

Prouvé himself is the subject of the pavilion’s second room. This 20th century architect and designer innovated prefabricated architecture, and excelled in metal walling, yet many of his ideas failed to make it past the development stage. Under the heading ‘Constructive Imagination or Utopia’, the display seems to ask whether this was a missed opportunity.

The third room picks up on this production-line approach to architecture, focusing on how after the war; "big industry seizes the building," as Le Corbusier once put it. Reinforced concrete joins the metal walls Prouvé pioneered, as the early modernist dreams are made real in many French city.

Finally, the pavilion rounds off its displays with a meditation on the kind of French mass housing most of us know about: the ring-like estates built on the outskirts of the city, which were supposed to house its masses. Constructed in a hopeful era, Cohen and co seem to acknowledge that these suburbs, or banlieues, are now a symbol of social exclusion.

It’s a remarkably frank examination of the country’s heritage, and all the more impressive, as it’s overseen by the national cultural body, Institut Francais. Find out more here.

For more on last century's architecture, consider our 20th Century World Architecture Atlas, as well as our Le Corbusier books. You can find out more about the the latest developments in building design via our Online Atlas. Meanwhile, for more on contemporary architecture, please take a look at The Phaidon Atlas of 21st Century Architecture and the Phaidon Architecture Travel Guide App.