Why is Cliff Richard in the British Pavilion?

Sam Jacob and Wouter Vanstiphout’s show at the Venice Architecture Biennale takes a pop view of town planning

There are few exhibitions where the works of the aged British rock 'n' roll singer Cliff Richard are presented alongside images of post-punk band Joy Division; fewer still that are on the subject of town planning. How should we judge this poppy and provocative line-up? As a call to reconsider British modernism says co-curator Sam Jacob, ex-of the FAT British architecture practice.

Jacob, working with the Dutch buildings expert Wouter Vanstiphout, from Crimson Architectural Historians, has assembled an intriguing response to British new towns. Called Clockwork Jerusalem, the exhibit in the British Pavilion at this year’s Architecture Biennale, which opens this week, responds to director Rem Koolhaas’s brief, Absorbing Modernity 1914-2014. Town planning, and modern architecture more generally, has met with a mixed response among the British public, who viewed the concrete and glass as an assault on British traditionalism and pastoralism.

However, Clockwork Jerusalem presents the tradition of town planning in places such as Milton Keynes, as being in keeping with Britain’s Christian, bucolic ideals. The curators explain in the Architects' Journal that the show, “explores how responses to the industrial city combined with traditions of the romantic, sublime and pastoral to create new visions of British society.” They add that, “These visions looked simultaneously backwards and forwards, combining in one sweep science fiction and historicism to form ideological and aesthetic approaches to the contemporary city.”

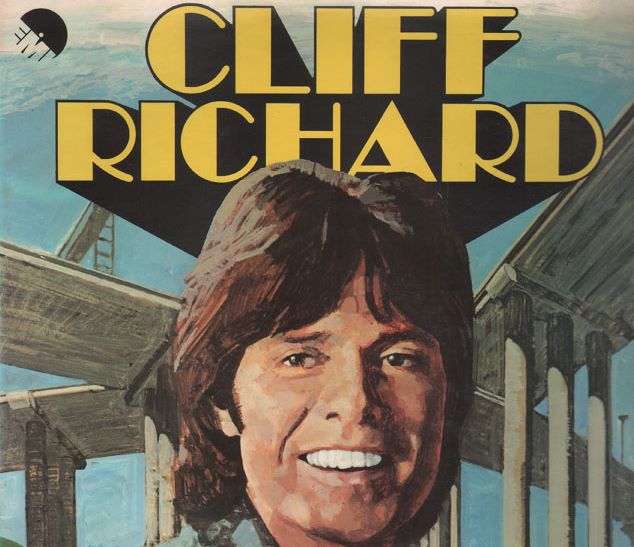

Joy Division appear in shots taken by rock photographer Kevin Cummings, beside the Hulme Crescents, a notoriously dysfunctional public-housing block, which, nevertheless, housed and fostered many of the city’s best-known musicians. Cliff Richards, meanwhile, is included on the strength of his Wired for Sound video, which features the singer rollerstaking around Milton Keynes, a purpose-built British town, and his Take My High cover, which superimposes Cliff’s face onto a backdrop of the Gravelly Hill Interchange, better-known as Spaghetti Junction.

These slightly frivolous inclusions are accompanied with more earnest meditations on British new-town building, which was once pioneering and now, in an age of housing shortages and high prices, is ripe for reconsideration.

“There’s a myth that we don’t like planning and that we are not very good at it,” Jacobs told the London Evening Standard. “Britain was a world leader. Planning was not only bureaucratic and technocratic, it was imaginative — a drawing of trees could be an idea of a city. In an age when London faces rapid change and many challenges — partly brought about by its own success — we need a new plan for London that can pick up where the last visions ran out. We need new ideas.”

It’s a sentiment the pair echo in the Guardian; there they write that “Our show doesn’t hold the answers to Britain's future. But we hope it can remind us all that even at the darkest moments, when our built environment seems subject to uncontrollable forces that imagination – both professional and popular – can invent new ways out.”

For more go here. If you're in Venice this week, do join Phaidon Atlas Editor, Jean-Francois Goyette at the British Pavilion June 6, 3-4pm, for in what promises to be a fascinating discussion with architects Stephan Petermann from OMA, Ma Yansong from MAD architects and Diébédo Francis Kéré from Kéré Architects to discuss whether contemporary architecture should pursue national forms or revel in a globalised culture.

You can find out more about the Online Atlas here. Meanwhile, for more on contemporary building, please take a look at The Phaidon Atlas of 21st Century Architecture and the Phaidon Architecture Travel Guide App.