How Louis Kahn's drawings changed his architecture

New show and Phaidon monograph show how drawings from Egypt influenced use of form, light and shape

Architectural drawings and sketches often serve as an insight into the early ideas behind what can then become an iconic building, celebrated both in our lifetimes and in ones to come.

In the case of Louis Kahn however, his drawings were, on occasion, not only the driver behind a new building but a complete about turn in his entire architectural practice.

In graphite, watercolour and crayon, they are, on the whole, an astonishing body of work, in contrast to the formalism of his buildings, cloaked in an air of romanticism which brings to mind the work of the artists - Picasso and Matisse especially – who inspired him.

Kahn's drawings, like his work, were inspired by his extensive travels, both in his early trips to Europe and, in later years, beyond. His architectural experiments with light, form and shape are presciently foreshadowed in the sketches themselves as they progress from the earliest simple outings to the energetic flourishes he brought to them in later years.

A new Louis Kahn’s exhibition at the Design Museum looks at these travel sketches alongside Kahn’s architectural models, photographs and films. Highlights of the exhibition include a four-metre-high model of the spectacular City Tower designed for Philadelphia in 1952.

Looking through the drawings sent us back to our wonderful monograph on Kahn written by Robert McCarter (also the author of our fine Carlo Scarpa book). In particular the chapter where Kahn, based at the American Academy in Rome in 1950, alighted on a number of expeditions abroad in search of inspiration.

In January 1951 Kahn visited Egypt and Greece, travelling from once ancient site to the next over the following two months. Author Robert McCarter takes up the story.

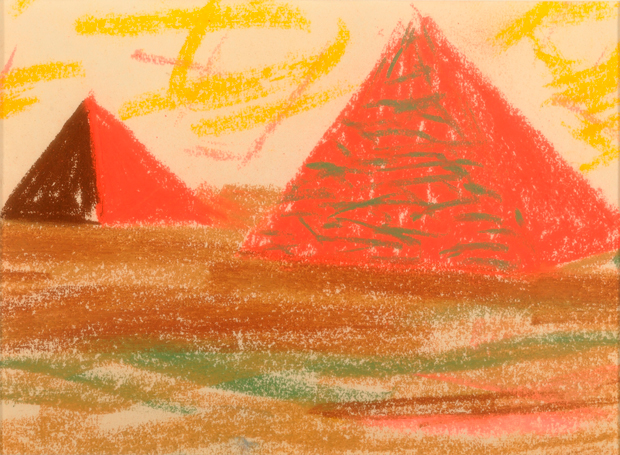

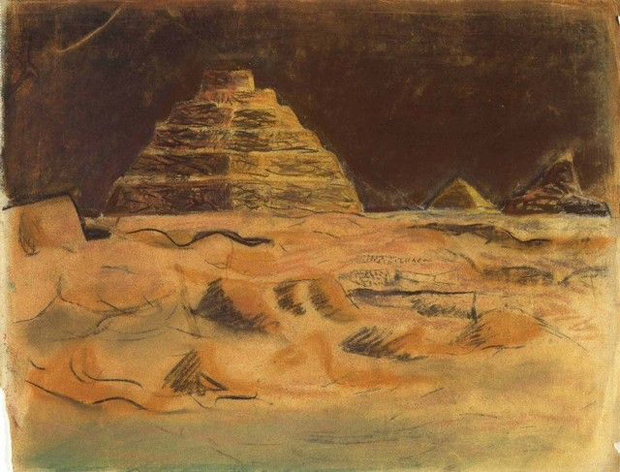

“The group was briefly delayed in Cairo, allowing Kahn a week at the pyramids at Giza, which astonished and overwhelmed him. Kahn’s pastel drawings of the pyramids are alive, their pure geometries and earth-tone colours transformed by the sunlight. The drawings reveal that Kahn saw the pyramids not only as enormous masses, timeless and eternal, but also as vehicles of light….reflectors of the sun’s rays. Kahn’s drawings of the temple complexes at Luxor are equally powerful, reflecting both the intensity and movement of the light and the weight and permanence of the stones.

As the book points out, this period of historical discovery would prove to be pivotal in Kahn’s development as the most important modern architect of his time. It led to his renewed understanding of the importance of history in contemporary design, summarized by his saying that ‘what will be has always been.’

The eternal quality of heavy construction and the spaces shaped by massive masonry made a lasting impression on Kahn. This is evidenced by the fact that, though the building he had completely just prior to leaving for Rome (the Pincus Occupational Therapy Building) was of steel construction, after his three months abroad Kahn would never again make use of lightweight steel structures, building only with reinforced concrete and masonry.

McCarter goes on to reveal that during his time at the American academy in Rome, Kahn made a startling decision: from that time forward he would not build with light and thin materials but would instead make his architecture out of heavy and thick materials – the structural mass out of which was constructed the great architecture of Rome, Greece and Egypt, which he had recently so movingly experienced. Kahn’s refusal to employ the structural construction materials most typical of modern architecture was in effect a rejection of modern architecture’s pronounced privileging of lightness, exemplified by Buckminster Fuller’s rhetorical question, “how much does your house weigh’ .

If you're planning on attending the Design Museum show we urge you to buy a copy of our Louis Kahn book - you'll get so much more out of it with a bit of reading beforehand. It's in the store here and if you'd like to go further with architecture take a trial with our online Atlas and if you're on the move this summer download The Phaidon Architecture Travel Guide App before you go.