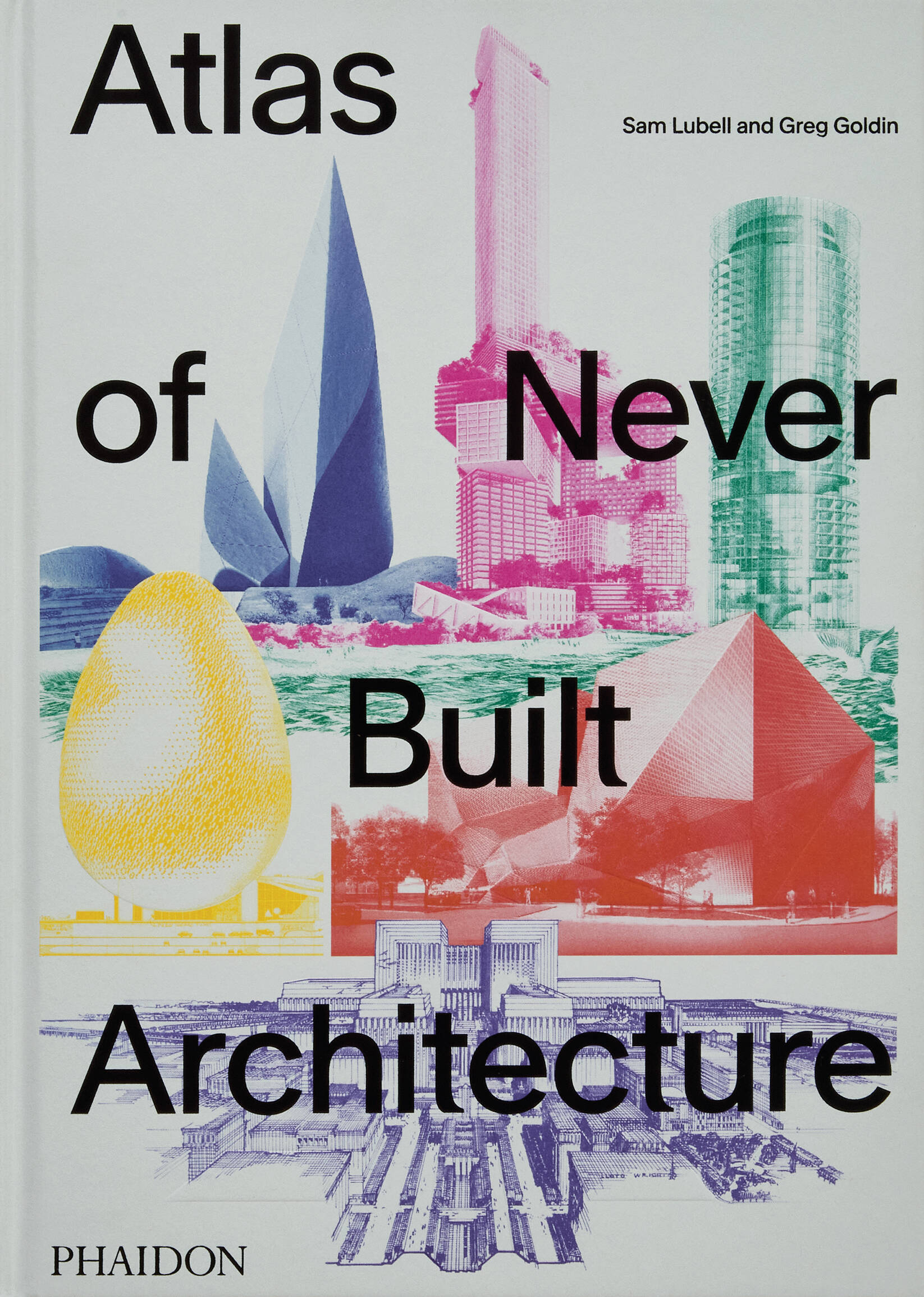

Sam Lubell and Greg Goldin tell you about their new book the Atlas of Never Built Architecture

Museums, art galleries, cemeteries, churches, bridges, skyscrapers, hotels, casinos, opera houses, and even a theatre boat that looks a bit like a UFO - imagine how different our world might have looked

Imagine how different our towns and cities might look in a world where time, politics and money are of no real consequence – a world where the only real limit is the imagination of the architect.

The Atlas of Never Built Architecture, by Sam Lubell and Greg Goldin gives you a glimpse into such a world.

The book presents more than 300 fascinating unbuilt projects from all over the world in a comprehensive, geographically-arranged survey. It features work by iconic architects of the twentieth century – including Mies van der Rohe, Frank Lloyd Wright and Le Corbusier – as well as some of the best contemporary talent such as Zaha Hadid and Norman Foster.

The diverse array of imagery, from initial sketches and paintings to etchings and digital renderings, offers insight into how architectural projects are conceived and developed.

Hidden behind the landscapes of the world’s great cities are the ghosts of skylines that could have been – parallel metropolises that reveal an alternative history. The Atlas of Never Built Architecture examines the extraordinary range and diversity of proposals that emerged from the beginning of the 20th century to the present day, that never made it off the page.

Lubell and Goldin – both experts on the subject of unbuilt architecture, and co-curators of the hit exhibitions Never Built New York and Never Built Los Angeles – have spent years engaged in the mammoth task of delving into archives, architectural studios and history books to pull the list together.

Many of these grand projects were flights of fancy that couldn’t be built, others were simply forgotten or fell to the cutting room floor due to lack of funding, war or a change of regime, but ultimately all of them represent the ambition of the architectural imagination.

You’ll find a 400-foot tall crystal pyramid conceived to add some spice to Toronto’s skyline, a short-lived 1930s plan for an airport on an island in the middle of Paris, and Frank Lloyd Wright’s audacious 528-storey tower for Chicago, which he designed at the spritely age of 89.

But that’s just the tip of the architectural iceberg – you’ll also discover museums, art galleries, cemeteries, churches, bridges, skyscrapers, hotels, theme parks, casinos, opera houses, government buildings and even a floating theatre boat that looks a bit like a UFO. Together, they create what could have been a strange and wonderful new world.

In the first of a two part interview we asked Sam and Greg about the research for the project, the particular favourites they uncovered and the impact of never built architecture on the architect.

Siloo O, NL Architects, Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2011. Picture credit: NL Architects

Siloo O, NL Architects, Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2011. Picture credit: NL Architects

Essentially this is a book of dashed hopes and dreams! But what did it mean to you?

Greg There’s no simple answer to that question and that’s true for both of us. Partly it’s the treasure hunt. I know that sounds a little less artsy than it should sound. But truth is that Sam and I love to dig and discover things that other people haven’t seen or that have been neglected, forgotten, ignored, underrated all of the above and more. So part of this is about can we find something somewhere that nobody really has laid eyes on, or paid attention to. That’s part of what the book means for us. We hope that this is a journey of discovery for our readers too.

Church of the Blessed Virgin Mary, Queen of Poland, Witold Jerzy Molicki, Maria Molicka, Gorzów Wielkopolski, Poland, 1986. Picture credit: Museum of Architecture in Wroclaw

Church of the Blessed Virgin Mary, Queen of Poland, Witold Jerzy Molicki, Maria Molicka, Gorzów Wielkopolski, Poland, 1986. Picture credit: Museum of Architecture in Wroclaw

So much research has gone into it.

Greg Yes, it’s not easy. It’s a labour of love. I know that’s an overused phrase, but nobody could do this unless they were really determined to find things that are not catalogued, you can’t take a picture of, that nobody can be sent out to take a picture of. It doesn’t exist and to say it doesn’t exist really means that most of what we look at is completely buried and you’re lucky if it’s even in an archive.

Sam Dashed hopes and dreams is a funny thought, because obviously that is a part of this, but for us there’s a hopefulness to it too. There’s a striving to form these ideas and solutions that is inspiring. When you’re in never built territory you’re into things that are on the edge of what people are willing to accept and able to build, scratching the surface of what’s possible and what can be done. It’s an interesting zone to be in and one where a lot of good ideas come out.

Art Museum Strongoli, Coop Himmelb(l)au, Strongoli, Italy, 2009. Picture credit: ISOCHROM.com / Courtesy of COOP HIMMELB(L)AU

Art Museum Strongoli, Coop Himmelb(l)au, Strongoli, Italy, 2009. Picture credit: ISOCHROM.com / Courtesy of COOP HIMMELB(L)AU

How did you go about the incredible amount of research necessary to create the book?

Sam I’ll talk about the first phase. A lot of it comes down to the fact that to find out about never built work you have to know about built work. And so when you do, you inevitably find that the architect will have never built work. So wherever you go you have to get familiar with the players in each place. Once you know they exist, once you get the lead, then you go down the rabbit hole.

The trick is to know who’s done stuff, and who’s important, and who’s been overshadowed - even if it’s a house. There’s an architect we love called Charles Deaton who did the Sleeper House, the space age house from the Woody Allen movie, Sleeper. When we looked at his stuff we found that he had plans for these massive convertible stadiums and skyscrapers and so we thought, oh yeah, this one’s a good lead. So that’s a big part of it in the initial stages.

Crystal Palace Sculpture Park, WilkinsonEyre, London, England, Great Britain, 2003. Picture credit: Wilkinson Eyre / Sketches by Chris Wilkinson

Crystal Palace Sculpture Park, WilkinsonEyre, London, England, Great Britain, 2003. Picture credit: Wilkinson Eyre / Sketches by Chris Wilkinson

Greg Deaton is a perfect example because partly what happens is it always begins with an image, and Sam is more diligent at this than I am. He finds images that tickle our fancy. But images are all over the internet. There are people putting stuff up online everywhere but that doesn’t mean it’s the image you want, but it may point the way.

The trick is to find out what is the narrative that lays behind that building, and that process is harder. If you know where an image comes from, sometimes the archive where it resides will also have the architect’s papers.

Then, if the archivist is friendly, they’ll photograph things and send us pictures of the documentation. If it’s in Dutch you have to sit there and translate it and try and figure out what’s going on! We reach out to other researchers, architectural historians to get them to tell us the stuff we’re not seeing and who are the people we should be looking at. Often they’ve done a lot of research and they’re generous in helping us to get to the story. It’s a constant effort to find the people who know those people who might be sitting on documentation.

For instance, the Rasch brothers (Heinz and Bodo) were these incredibly inventive, feuding, duelling brothers in 1920s Germany. They made these series of proposals for suspended housing projects. The drawings are remarkable, and the ideas are really brilliant. They got into lawsuits with (Marcel) Breuer over his chairs. They were in the thick of every idea that came out of Germany in the early 20s but they totally self-destructed.

The hard part is the minute you leave the first world you enter into a much more impenetrable realm, which reflects the instability of a lot of the rest of the world and the lack of resources. Any time there’s regime change things are lost or destroyed. So it can be very hard to reconstruct the history of something. So you might find a proposition, but you’ll be lucky to find the story behind it.

In some places, the value of drawings and architectural holdings are just not treated the same way as in the US and Europe. So even though a Brazilian architect may have a global reputation. It doesn’t mean that there’s one central place in, say Sao Paulo, to find their work.

Temple Of Atomic Catastrophes, Seiichi Shirai, Hiroshima, Japan, 1954. Picture credit: Reproduced with permission of Seiichi Shirai / The Shoto Museum of Art

Temple Of Atomic Catastrophes, Seiichi Shirai, Hiroshima, Japan, 1954. Picture credit: Reproduced with permission of Seiichi Shirai / The Shoto Museum of Art

There's so much in the book, is it possible for you to have personal favourite Never Built Architecture favourites?

Sam I’m really bad at favourites but I like some of the bigger surprises. I like finding projects by people who are not as heralded but would have been heralded. We mentioned Charles Deaton as one, but Matthew Nowicki is a great example. He was a Polish American architect who was very active in Poland and moved to the States. He was becoming a superstar and was tasked to design Chandigarh, but he died in a plane crash, so it never happened, and Corbusier did Chandigarh. You look at the plans he did for that and it’s clear why he would have been a star. Then you start discovering his work and it’s so inspiring.

There was an architect in Hungary, Imre Makovecz. His stuff was this incredible merger, very modern and very organic, like Art Nouveau on steroids. He did this incredible youth centre that we have in the book inspired by whale chest cavities – incredible things - that are so organic, not dainty organic but almost like brutalist organic.

Things like that that I just had no idea about. For me it broadened my perspective on what’s possible in architecture. And you get examples of that from all over the world. People that didn’t get world acclaim because nothing got built - or it did - but it was localised. That’s my favourite part about this project, learning about architects and designs all over the world that I just didn’t know very well.

Das Haus Der Freundschaft, Hans Poelzig, Istanbul, Turkey, 1916. Picture credit: Architekturmuseum TU Berlin.

Das Haus Der Freundschaft, Hans Poelzig, Istanbul, Turkey, 1916. Picture credit: Architekturmuseum TU Berlin.

Greg One of my favourites became Pancho Guedes who grew up and practised in Mozambique. His work is almost as if the flora and fauna of where he lived was somehow transmogrified into buildings. I don’t know how else to put it. He’s really unique, and there he was, in a far corner of the world, doing what he did.

He was a painter, so his drawings are as far from a conventional architectural image as you’ll get. It’s not that he didn’t do proper drawings for buildings, he did, but when you look at the renderings they’re like Rorschach tests. They’re something else, really compelling. He’s as far from a household name as you could ever come across. And so, for me, that stuff becomes a favourite, partly because it’s so unexpected. You definitely do not expect to find that kind of work anywhere. It’s serendipity if or when you come across it.

Festspielhaus, Hans Poelzig, Salzburg, Austria, 1922. Picture credit: Architekturmuseum TU Berlin.

Festspielhaus, Hans Poelzig, Salzburg, Austria, 1922. Picture credit: Architekturmuseum TU Berlin.

Sam We are suckers for the weird. One of my favourites is a fantastic architect called Gunnar Birkerts. He had a project for the CEO of Domino’s Pizza (Tom Monaghan) Called the Monaghan Tower which was nicknamed The Leaning Tower of Pizza. It was designed as a tower to lean on supports. He thought that vertical was neutral, and he’d done enough neutral in his life. There are all kinds of weird things that are justifiable in ways that aren’t weird - even though they are weird. And we love them because they’re hilarious and there’s not enough humour in architecture, and they’re just great stories.

Obviously there are often prosaic reasons why designs don’t get built, but what were the more unusual ones you came across?

Greg A lot of things are shovel ready; the backing is there; the money is there and then something unexpected can happen: the Prince of Wales or Fidel Castro may intervene! One person with sufficient power weighs in and every single part of a plan blows up. Or a CEO is ousted, and the next guy shows up and is not into it.

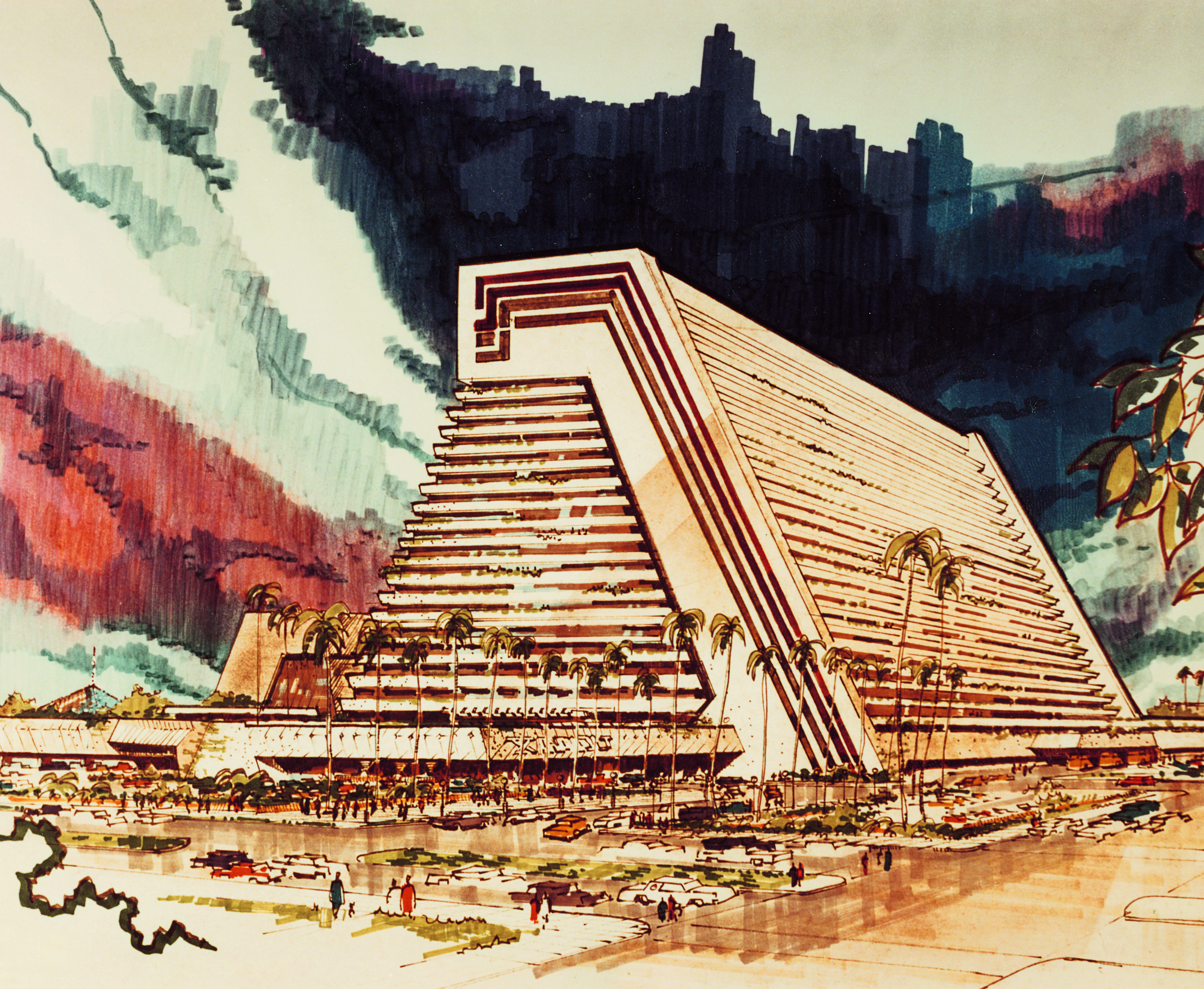

Xanadu, Martin Stern, Jr, Las Vegas, Nevada, (US) 1975. Picture credit: Special Collections and Archives / University of Nevada, Las Vegas

Xanadu, Martin Stern, Jr, Las Vegas, Nevada, (US) 1975. Picture credit: Special Collections and Archives / University of Nevada, Las Vegas

Sam There are some that are never meant to be because they are perhaps pure swindles designed to get people’s money. I hate to bring up Donald Trump, but there are schemes that he never intended to build. He’d want to increase the value of the land so he would have an architect draw some plans up with no intention of ever building it.

But one of my favourites is this science centre in Riyadh that was going to be designed by Douglas Cardinal. He’s a Canadian architect. He designed the Smithsonian native American museum, and he was commissioned to do this amazing science centre in Riyadh that looked like sculpted dunes, with monorails going through it.

The patron was Sultan bin Salman Al Saud. He was very interested in space - so interested he went up there on a space mission. They called him The Astronaut Prince. The story that Douglas told me was that when he came back to earth it had changed his Saudi-centric view of the world, and he became more interested in global cooperation and less interested in Saudi primacy and, as a result, he fell out of favour with the family and had less power; so with that the project fell away as well.

Stone Towers, Zaha Hadid, Cairo, Egypt, 2009. Picture credit: Courtesy of Zaha Hadid Architects

Stone Towers, Zaha Hadid, Cairo, Egypt, 2009. Picture credit: Courtesy of Zaha Hadid Architects

We think of architects as incredibly level-headed people, but are they affected when a proposal bites the dust?

Greg I’m sure it’s happened. An architect may permanently associate certain projects that remain unbuilt with their body of work and perhaps among the highest expressions of their talent, or gifts, or hopes, for that what they can achieve as architects. So you sometimes see the ideas seep into other projects that they do or that other architects do, because architects are always looking at each other’s work.

For example: Peter Eisenman’s unbuilt Max Reinhardt house – this mobius strip-like proposal is circulated all over the place. And then you get Rem Koolhaas’s CCTV tower in China, and you realise that Koolhaas has borrowed this concept. That’s got to burn! I’m fictionalising this to some extent, but I wonder how an architect is going to feel about their unbuilt work when they see it surface in someone else’s work.

Sam I sometimes wonder if there is a level of bitterness. Because some of these architects would have been household names if these buildings had happened. And now you don’t know who they are. We’ve talked with Daniel Libeskind about this a couple of times, and I like what he has to say about it which is that an architect has to love it so much because if it doesn’t get built it’s OK.

It’s not that it’s easy but it’s not a shock when these things don’t happen because it’s part of the profession. But yes, it must be hard to face the fact that this thing that you’ve been putting your heart and soul into for years has gone away.

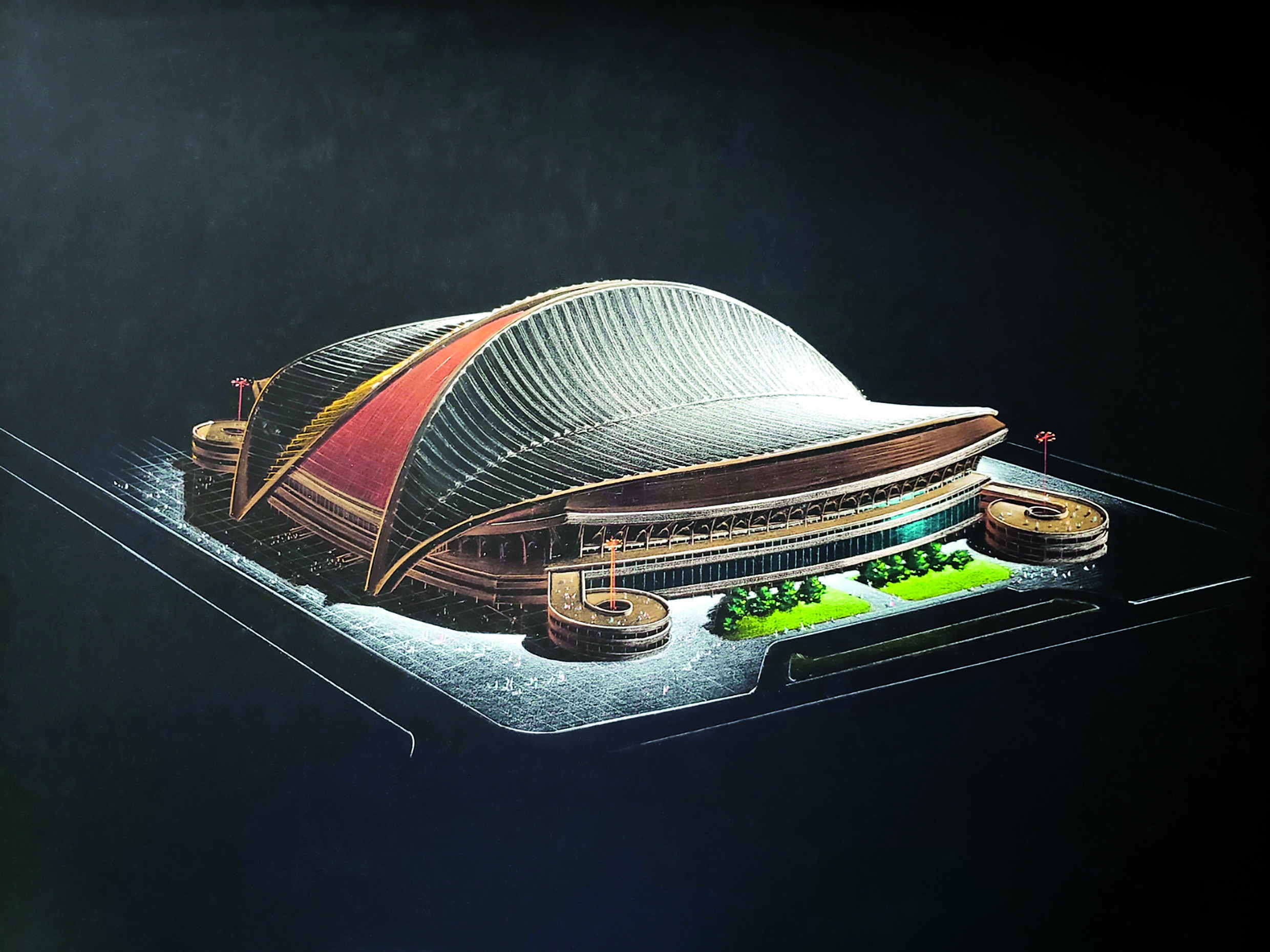

Chicago Convertible Stadium, Charles Deaton, Chicago, Illinois, United States, 1986. Picture credit: Courtesy of Nicholas Antonopoulos

Chicago Convertible Stadium, Charles Deaton, Chicago, Illinois, United States, 1986. Picture credit: Courtesy of Nicholas Antonopoulos

Obviously the power of the images is important in a project like this, you have uncovered some truly beautiful ones.

Greg When architects use their own hand to draw something it almost always conveys so much more than what we have now become accustomed to in the way of computer generated renderings. There really is nothing quite like the first hand encounter; that experience of seeing how an architect saw their own idea on paper. It is so moving. It takes you to a place of real meaning for a building.

It’s part of the expression of architecture that an idea is put on paper in a way that the emotional sense of what a building is - the palpable sense of what it might be like to experience it as a three-dimensional space - can be conveyed.

If the drawings are really spectacular we’re inclined to think of that as a never built we would like to know more about. It’s part of what convinces Sam and I to choose one project over another. That connection is more and more being ruptured by the depleted state of renderings now. But that I think is what leads us down that crazy path that we go on to unearth the real mystery behind an individual project. It starts with an image. it’s a drawing that captures or hooks us in.

Sam The most important thing of all that I would love people to take away is how does an image portray an idea so that you instantly understand that idea. It’s not just a surface thing, it’s how it is portrayed, how are we portraying this ingenious idea that still has relevance today? For instance: a tower that Louis Kahn made that’s hanging from a truss in a way that is ingenious - and how does that get portrayed in a drawing that you immediately understand why that idea is so brilliant? There are so many valuable ideas here. And to me so many of them are still relevant even if they’re a hundred-years-old.

Greg Goldin (left) and Sam Lubell

Greg Goldin (left) and Sam Lubell

Look out for part two of our interview with Sam and Greg and get a copy of The Atlas of Never Built Architecture here.