The artistic Louis Kahn

Did you know one of America’s best-loved architects nearly opted for a life in fine art and music?

Our newly updated monograph on the life and work of Louis I Kahn celebrates the life of one of the 20th century’s finest architects. Yet, it also sheds light on lesser-known sides of this great man. Did you know, for instance, that if Kahn made different choices in his early life, we might now be praising him as a fine artist or concert musician?

In Robert McCarter’s revised and expanded book, Louis I Kahn, the author describes how Kahn – born 20 February 1901, in Estonia – was raised in a household where the arts were practised and prized. The architect’s father’s “beautiful handwriting secured him work as a scribe and paymaster for the Russian army, and it was he who encouraged Kahn to draw from an early age,” writes McCarter.

Kahn’s mother, meanwhile “was related to the German Romantic composer Felix Mendelssohn, as well as the composer’s grandfather Moses Mendelssohn, the famous Jewish philosopher of the German Enlightenment. Kahn’s mother was a gifted musician, and Kahn credits her with his deep appreciation, considerable talent and sophisticated knowledge of music.”

Upon emigration to Philadelphia, Kahn's artistic talents won him cash work, as a pianist at a silent-movie theatre (when the theatre replaced its piano for an organ, Kahn learned to play the new instrument in an afternoon, McCarter notes). His skills also secured him academic rewards; as a young man he was offered a music scholarship and a fully paid place at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. Ultimately, Kahn chose to decline these offers, and instead take a place on the architecture course at the University of Pennsylvania, yet his feel for the arts, and his own personal artistry remained with the architect throughout his professional career.

McCarter’s new book reproduces one of pastel renderings of Siena’s medieval Il Campo square, one of the finest public spaces in Europe. The work, executed in 1950, by which time Kahn had established himself as an architect, “shows how the masonry walls and pavements are brought to life by the strong sunlight that seems to pour into and fill the spaces, making their surfaces glow in rich yellows, reds and oranges, with both green and black shadows.”

Kimbell Art Museum, Forth Worth, Texas, USA, 1966-72. Photo by James Florio

This deep understanding of the play of light would serve Kahn well in his greatest contribution to the world of fine arts: the Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, Texas. Finished in 1972, it was the last building designed by Kahn that he lived to see completed, and in McCarter’s words, “is rightly considered Kahn’s greatest built work, in that it fully integrates and brings to the highest level of resolution all the elements composing Kahn’s conception of architecture: archaic and modern, mass and structure, light and shadow, room and garden, the poetics of action and construction.”

The Kimbell was commissioned by the museum’s director, Richard Brown, who prized natural light. In response, Kahn argued that the Old Masters in the museum collection were made in natural light, “and thus are best viewed in the same ever-changing light,” writes McCarter.

The architect brought light into the Kimbell’s galleries with a series of half moon ‘cycloid’ vaulted ceilings, each split along its centre with a skylight. Light falls onto a central reflector, to give each room natural, though diffuse day-lit illumination.

“Here I felt that the light in the rooms structured in concrete will have the luminosity of silver,” Kahn said of the Kimbell. “The scheme of enclosure of the museum is a succession of cycloid vaults each of a single span 150-feet-long and 20-feet-wide, each forming the rooms with a narrow slit to the sky, with a mirrored glass shaped to spread natural light on the sides of the vault. This light will give a glow of silver to the room without touching the objects directly, yet give the comforting feeling of knowing the time of the day.”

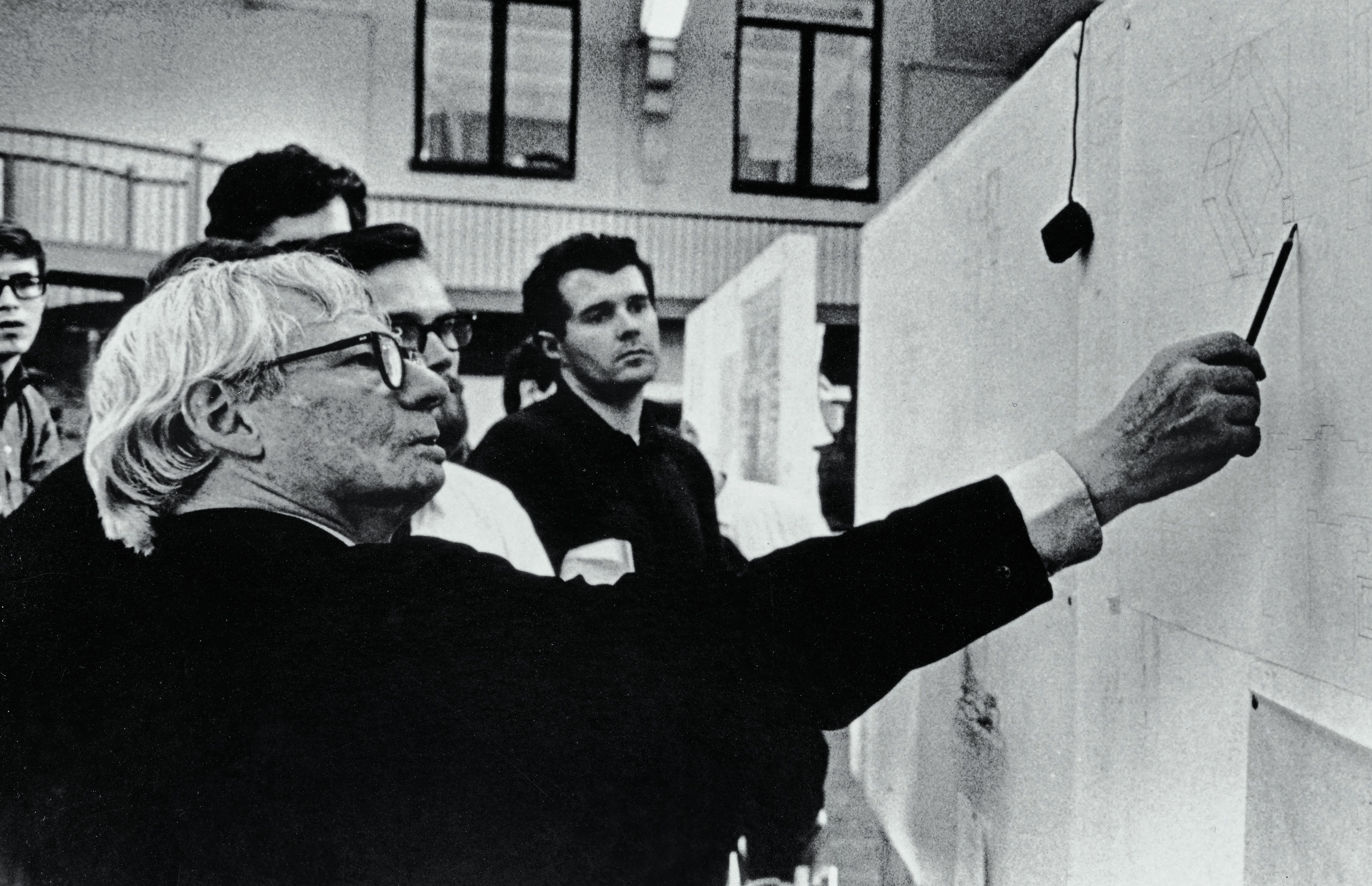

Louis Kahn teaching graduate architectural studio, University of Pennsylvania, USA, c.1967. Photo by Eileen Christelow

Upon its opening in October 1972, the Kimbell was hailed as a success, winning praise for its utilitarian, functional design, offering directors and curators a well-lit space free from columns, piers or windows. Yet McCarter goes further, praising the gallery as a work of art in and of itself.

“Without question Kahn’s most beautiful space, the Kimbell Museum is also his most effective engagement of the poetics of construction, as well as the most rigorously resolved example of his concept of the relation between light, structure and space,” he writes, “the interior spaces receiving natural light in a variety of ways that together precisely outline and articulate the structural elements.”

Kahn may have favoured architecture over fine arts, yet his feel for sublime aesthetics lives on in his, one of his greatest works. To learn more about this important architect, order a copy of Louis I Kahn here.